This is an interview with Dr. Mulaika Hijjas, who runs The Jawi Transcription Project on FromThePage. What is Jawi? Read on to find out!

Dr Mulaika Hijjas is Lecturer (=Associate Professor) in South East Asian Studies at SOAS University of London. Originally from Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, her research focuses on the Malay manuscript tradition, Islam and women in the Malay world, but she also teaches other aspects of classical and contemporary South East Asian literature and cultural studies. She is co-managing editor of the journal Indonesia and the Malay World.

First let me ask, what is Jawi?

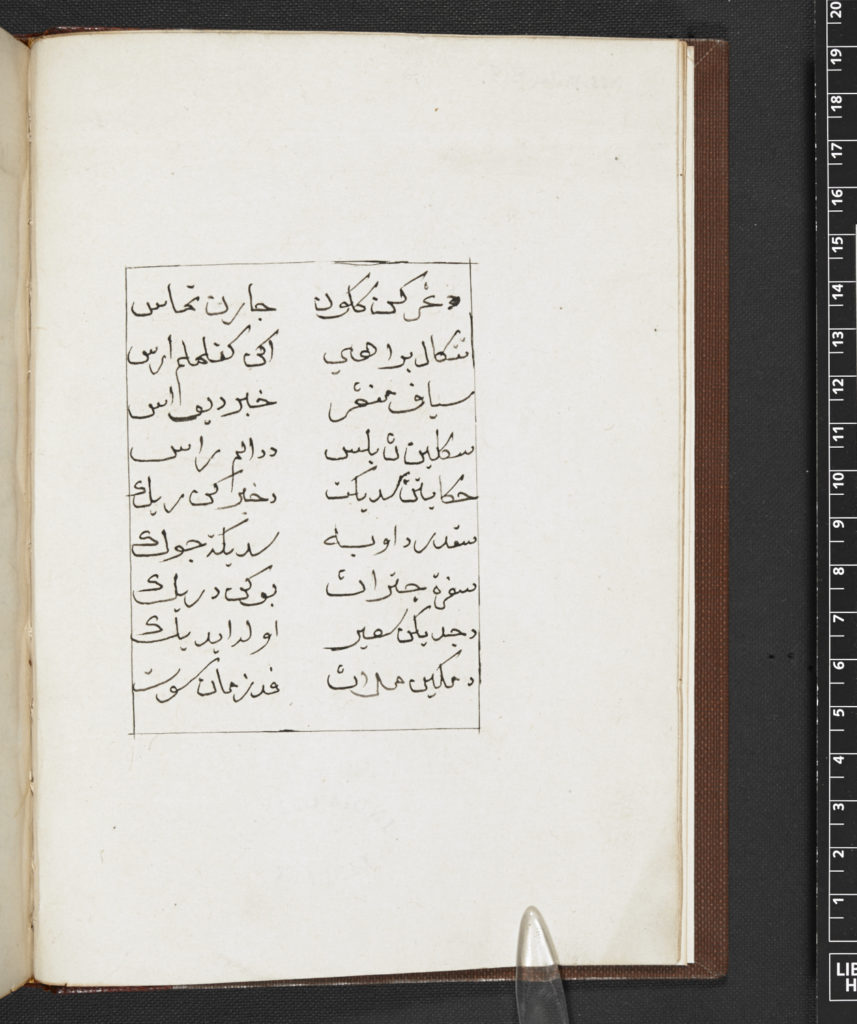

Jawi was the script most commonly used to write the Malay language between the 14th and early 20th centuries. It is adapted from Arabic and Persian scripts—it’s basically the same set of letters, but with a few extra ones for sounds that don’t occur in those languages (like /ng/).

Although the Roman script became the norm for writing Malay and its offshoot, Indonesian, in the early 20th century, many people are still able to read Jawi because they have learned Arabic letters as part of their basic Islamic education. However, Jawi is slightly trickier to read than Arabic, as it is not morphologically predictable. Jawi usually only gives you the consonants and some vowels, which means that there are a lot of possibilities and the correct one can only be chosen based on context. For example, the sequence k-m-b-ng might be read kambing (goat), kumbang (beetle), kembang (flower) or even gambang (a musical instrument)… OCR for Arabic is, as far as I understand it, a long way off, in which case I imagine OCR for Jawi is even further away. On the other hand, someone with a good command of the language (and there are over 280 million speakers of Malay/Indonesian) can figure it out fairly easily.

Tell me about the contents of the documents.

The text is a narrative poem about a hero called Jaran Tamasa, and his romance with the heroine, Ken Lamlam Arsa. At least, that’s what I think it’s about—it’s likely that no one has read this poem since the English philologist who commissioned the manuscript copy in 1805. He was apparently quite a fan, noting down some of its nicer turns of phrase (see this blog post by the British Library curator for more details).

Syair Jaran Tamasa is a Panji tale, which is a genre of traditional Malay literature revolving around the romantic exploits of a hero called Panji, who goes by many different names but is always in pursuit of his true love (though this doesn’t prevent him from a few other dalliances along the way). The stories are set in a mythical version of Java, which functioned for Malay audiences of the time as a sort of exotic Other, and usually feature lots of battles, drinking and romancing.

What are your goals for the project?

First, I want to see if crowd-sourcing Jawi transcription is possible! Most of the crowd-sourcing projects out there seem to be on European-language material, but presumably there’s no reason it can’t be used for other languages and scripts. In the case of Jawi, there are hundreds of texts that have never been read or studied since they entered the colonial archives. The rate of production of scholarly editions has dwindled to almost zero in recent years, which means that a lot of the written record for this large area of the world for the nineteenth century and earlier remains inaccessible.

I also want to involve people in rediscovering—indeed, recreating—this piece of literary history. I know there are a lot of very competent Jawi readers out there, some of whom may be interested in discovering more about their literary heritage. I could probably put together a transcription with a couple of weeks’ work, but then in all likelihood the text would remain unread. I want to find out if it’s possible to engage members of the public in Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and elsewhere in collaborating on recreating this text.

My aim is to get a workable transcription produced and to have it available freely online, ideally linked to the digitised manuscript on the British Library site, or to the Malay Concordance Project, which is basically the only digital philology resource for Malay manuscripts. This would then be searchable and accessible to scholars and members of the public alike.

But I would also really like to have the transcription published as a book. This has happened for another recently digitised British Library manuscript, Hikayat Raja Babi. After the manuscript was made available online, a Malaysian commercial publisher commissioned a transcription and then published it both as a free ebook and in print. So after 200 years, readers were able to rediscover a text and to read it for pleasure.

Do you or someone you know speak Malay? Try your hand transcribing Jawi for Dr. Hijjas!

Have your own transcription project -- in any language -- you'd like to start? Try a FromThePage trial, or contact us at support@fromthepage.com.