Last month, Ben and Sara Brumfield presented at a seminar -- Preserving Knowledge Diversity in Multilingual and Multicultural Context: Issues and Challenges for Information Science -- organized by Amel Fraisse at University of Lille in France. The presentation video and slides are below. (Retrouvez la version de cet article de blog en français ici.)

Presentation Video

https://pod.univ-lille.fr/video/20787-geriico_bensarabrumfield_17juin2021mp4/

Presentation Content and Slides

In brief, our platform allows people to see an image of a page and to transcribe the text from that page. We try to keep things as simple as possible for the users, because frankly, transcribing text is hard enough.

It’s also open source software run by institutions around the globe.

We should begin with a warning: while we would like to focus on multilingual and multicultural projects in this presentation, the majority of the users we see on FromThePage.com come from English-speaking countries: the United States, Great Britain, and Australia. Some independent installations of the software are primarily non-English, but we are most familiar with the projects hosted on our own software or that of of colleagues at the University of Texas-Austin. Many of the users of the UT-Austin system are from Latin America.

To make texts searchable.

This is a transcription project in Gaelic by University College Dublin. They “round trip” their transcriptions back into their digital library systems to make them full text searchable. The majority of projects on FromThePage are to get plaintext transcription into library systems for both reading and searching.

Transcription projects can also be for outreach. This is a project by the New Orleans Jazz Museum for a transcribathon featuring their colonial documents. They engaged French speakers and students of French from the New Orleans area to transcribe documents like this contract.

Another reason to transcribe is for teaching.

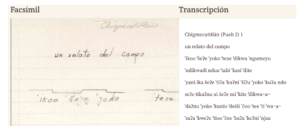

This example uses transcription to teach students Spanish paleography, and how to work with primary sources from 16th and 17th-century Spanish America.

You can transcribe to create training data for artificial intelligence algorithms. This medieval French text was transcribed as part of the Image du Monde Challenge. The resulting text was transformed into plaintext using the Medieval Unicode Font Extensions, then used to create a Transkribus model for Medieval French.

Modern scholars may need unpublished research from earlier scholars, such as these linguistic surveys of speakers of the Mesoamerican language Mixtec. By transcribing the responses, Linguists like Ryan Sullivant can analyze the Mixtec language spoken 40 years ago.

The results are encoded as datasets, and preserved in the AILLA repository.

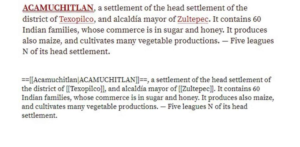

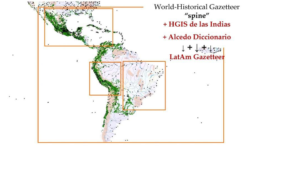

Historic Gazetteers may also serve as sources for GIS data-sets.

These required additional encoding to correct OCR and represent administrative hierarchy.

But the result was this impressive Pelagios LatAm Gazetteer.

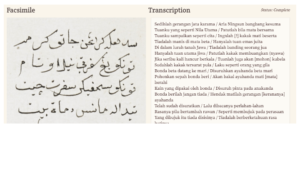

One important reason to transliterate is that spelling reform may make cultural heritage inaccessible to the public.

These folk tales are written in the Malay language, using the Jawi script, which is based on Arabic. Transliterating them into the Latin-based script used today makes them readable by modern Malay speakers.

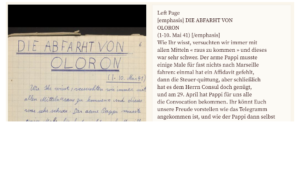

Sometimes translation is necessary for public access. This diary from the Second World War is held by the Archives of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. It records a German Jewish family’s attempt to escape Occupied France.

For it to be readable to an American audience, however, it must be translated into English.

In other cases, translation is necessary for researchers in different disciplines to collaborate.

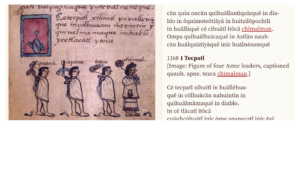

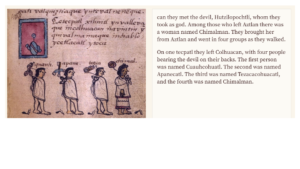

The Codex Aubin is richly illustrated, and of interest to art historians studying Aztec codices. However, few art historians understand Classical Nahuatl, the language of the text.

Translation by linguists allows the art historians and linguists to collaborate on the codices.

Similarly, medievalists studying legal texts may not have the command of Old French needed to work with original texts. As a result, they require translation for many legal historians.

Knowing the motivation for transcription and translation, what are the problems we have faced over the last five years?

How does language affect communication with contributors?

Volunteers often need “permission” to contribute. Both the interface language and the language of communication around the project may give them that permission or dissuade them.

In the Mixtec survey example, one volunteer left a few, short comments in English. When they were invited to communicate in Spanish, their contributions increased several times.

How does the language of the software interface affect transcription?

Even if texts can be transcribed from any language, the language of software itself is important. Thanks to a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, we have worked with our partners at the University of Texas Libraries to translate FromThePage into Spanish and Portuguese.

This enables not only transcription of Spanish and Portugues texts, but also indigenous-language texts like these colonial documents written in Nahuatl. We believe that meeting the expectations of users in Latin America will help connect them with the texts that are part of their history.

Interface language is even more important when…

There are a lot of indigenous communities working with colonial records for their own purposes. Many of these documents were not sympathetic to the communities.

Many indigenous communities want to work with texts for their own purposes, without intervention by outsiders.

The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe is transcribing primary sources in Dakȟóta/Lakȟóta to create material for language revitalization. The project is private; people outside the community may not even view it.

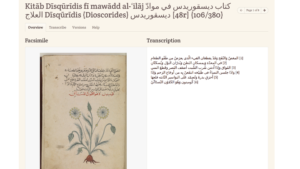

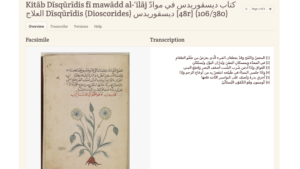

This is a project run by the British Library, asking volunteers to transcribe Arabic Scientific manuscripts in their collection. You see the Arabic text transcribe on the right -- and now start with the line numbers -- the justification is all wrong!

We had to add quite a bit of functionality to support right-to-left languages’ justification needs--reading the language of the document and setting text direction accordingly--even though, in theory, you “could” transcribe Arabic text. (And on another project we also found that some open source libraries we were using weren’t aware that Urdu is written right-to-left.)

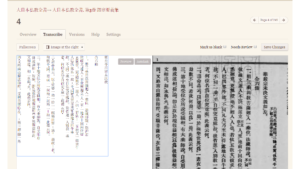

Worse, knowing the language of a text isn’t enough information to give you text direction! Modern Japanese and Chinese texts are written left-to-right, but older documents are top-to-bottom.

This screen is just a proof-of-concept created by Kiyonori Nagasaki to demonstrate the need for functionality encoding text direction.

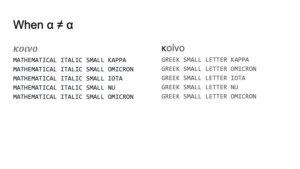

Another problem we discovered was that our database software supported Unicode, but the support was not complete.

We first saw a problem when a user attempted to transcribe a greek word within a text, and the software errored.

On investigation, we learned that the user had not used standard Greek letters, but had copied letters from a special keyboard that was used for mathematical symbols.

These symbols are represented in the Unicode Supplemental Multilingual Plane, which contains characters points larger than 65525. By default, many popular databases only support Unicode characters which can be stored in three bytes. This requires data migration to support characters above the Basic Multilingual Plane.

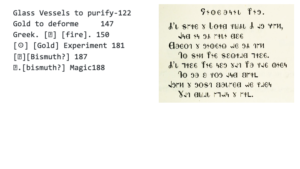

Do not think that this problem is limited to obscure languages!

Both of these texts are in English, and contain characters in the Supplemental Multilingual Plane. (Alchemy characters within a recipe on the left; a Mormon hymn written in the Deseret Script on the right.)

If your goal is to translate, do you need to transcribe? Many Urdu speakers in the west have never used an Urdu keyboard.

For this project we added a feature that allows transcribers to translate from an image rather than a transcription. A single step was faster and more respectful of volunteer time.

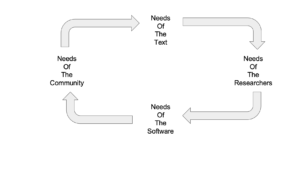

It's all connected.