I’ve been studying ways we might reduce errors--including my own!--in crowdsourced transcription projects. Part of that work has been analyzing a dataset of raw volunteer contributions to the Missouri State Archives death certificate indexing project, but another part has been reading what textual scholars have written about errors left by ancient and medieval scribes.

I’ve been studying ways we might reduce errors--including my own!--in crowdsourced transcription projects. Part of that work has been analyzing a dataset of raw volunteer contributions to the Missouri State Archives death certificate indexing project, but another part has been reading what textual scholars have written about errors left by ancient and medieval scribes.

Eugène Vinaver was a 20th century medievalist who edited Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur. In his 1939 article “Principles of Textual Emendation,” he drew on his experience editing different Arthurian manuscripts to classify the errors he observed in transcribed text. He described the ways that copying a text is different from composing a text in order to come up with a theory of why different errors were introduced (emphasis added):

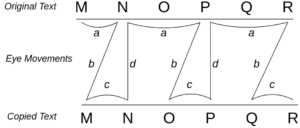

Mechanically speaking, original writing is a process limited to one plane--that of the page facing the writer. It is on this plane and on this plane alone that he moves his hand and fixes his eye, and there is no necessity for him ever to separate his line of vision from the movement of his hand. Not so with the copyist: his object is to transfer the text from the original to the copy, and his eye must travel at regular intervals from one to the other. While looking at the original he will endeavour to retain as much as possible of what he sees. The visual or mental impression thus received must then be transferred to the copy, and while the scribe’s eye goes from one to the other this impression must remain intact. Once it has been placed on the copy, the scribe must look again at the original. This time he has to bear in mind the last letter, word, or words he has written down so as to find in the original the point at which he left it a moment ago. Thus the process of transcription requires a constant shifting of the line of vision from one plane to another, and with each movement of his eyes the copyist has to carry mental or visual impressions which help him, first to reproduce part of his text, and then to find his way back to it. This may be shown by the following chart:

If it is admitted that this mechanism is the only distinctive feature of the process of copying, all we have to do is discover the possible irregularities in its working. Our chart shows that the scribe’s eye must perform four distinct movements: (a) the reading of the text; (b) the passage of the eye from the text to the copy; (c) the writing of the copy; and (d) the passage of the eye from the copy back to the text. Any accident that may legitimately be called a “scribal error” must, therefore, occur in the course of one of these movements, and in each case the character of the error will be determined by the conditions and the nature of the movement performed. (353-354).

How much of this is true in online transcription projects? Certainly Vinaver’s description of the mental process of copying seems accurate, and his diagram is so valuable for defining different parts of the copying process that David Greetham reproduced it in Textual Scholarship: An Introduction. It’s a great model for classifying when different kinds of transcription errors may occur, and for thinking about ways to minimize them. The problem is that modern transcribers do not necessarily work in exactly the two planes Vinaver envisions. That really comes out in this passage:

It stands to reason that movement c is not peculiar to the technique of transcription: it is the actual writing of the copy -- a process which belongs equally to scribal and authorial technique. Its working will be much the same whether the writer finds the words in his own mind or in a written document. An infinite variety of accidents may occur in the course of this movement--omission, dittography, misspelling, etc.--but we can never be quite certain what the accident is due to. (360)

Transcribing on a computer is in fact very different from composing text in a word processor, and varies depending on the level of skill of the typist. A touch-typist may not look at what they are typing, instead staring at the page image while they type without a glance at the resulting text. This can lead to errors that would never occur if an author were composing the same text: mis-placing hands on the keyboard can produce “Brtabt” in place of “Bryant” (MO Death Certificates Image Queue ID 1148409) or “Nekvub Hewek” for “Melvin Jewel” (1148759); accidental key-strikes can produce “Stella>u” for “Stella” (MO Death Certificates Image Queue ID 1147555). For field-based indexing projects, we see a phenomenon I call “tab-skip”, in which correct text is entered into the wrong fields, since the transcriber either missed the tab key or hit it twice instead of the once. A confident touch-typist may submit their transcript without even glancing at it. On the other hand, the kinds of errors Vinaver classifies as b and d might be reduced or eliminated, since the transcriber’s eye rarely leaves the exemplar.

On the other hand, a hunt-and-peck typist may introduce a third plane to Vinaver’s model, as they glance from image to transcript to keyboard and back again. It is not clear to me that this introduces unique kinds of errors yet.

How can we use Vinaver’s classification in software? We can try to help transcribers find their place by highlighting text in the original image as users transcribe it, moving the highlight as the typist moves from line to line or field to field. As we learned when building the screen ruler for FromThePage’s spreadsheet transcription feature, this may not be easy, since non-standard documents or irregular scans are likely to highlight the wrong thing altogether.

References

"Principles of Textual Emendation." Studies in French Language and Mediæval Literature Presented to Professor M.K. Pope. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1939. Print.

(Diagram based on Vinaver, with additional labels)

Image of Jean Miélot at his desk, Unknown miniaturist, Brussels Royal Library, MS 9278, fol. 10r. Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jean_Mi%C3%A9lot,_Brussels.jpg