On August 2, 2018, Meredith McDonough of the Alabama Department of Archives and History and Ben Brumfield of Brumfield Labs presented "Crowdsourcing the Alabama World War I Service Records" at the CONTENTdm User Meeting. Our fellow panelists were Phil Sager and Kristen Newby of the Ohio History Connection, who presented on the crowdsourced transcription system they had built for documents relating to Ohio's WWI centennial. This is a lightly edited transcript of the talk.

[Meredith] Like the Ohio History Connection, the Alabama Department of Archives and History has been heavily involved in the World War I centennial.

In the late 1930s, we received federal funding to construct a building that would both house the state archives and serve as the “Alabama World War Memorial.” So we’ve been waiting for this!

Over the past two years, we’ve uploaded hundreds of relevant items to our digital collections—letters, scrapbooks, sheet music, posters, but…

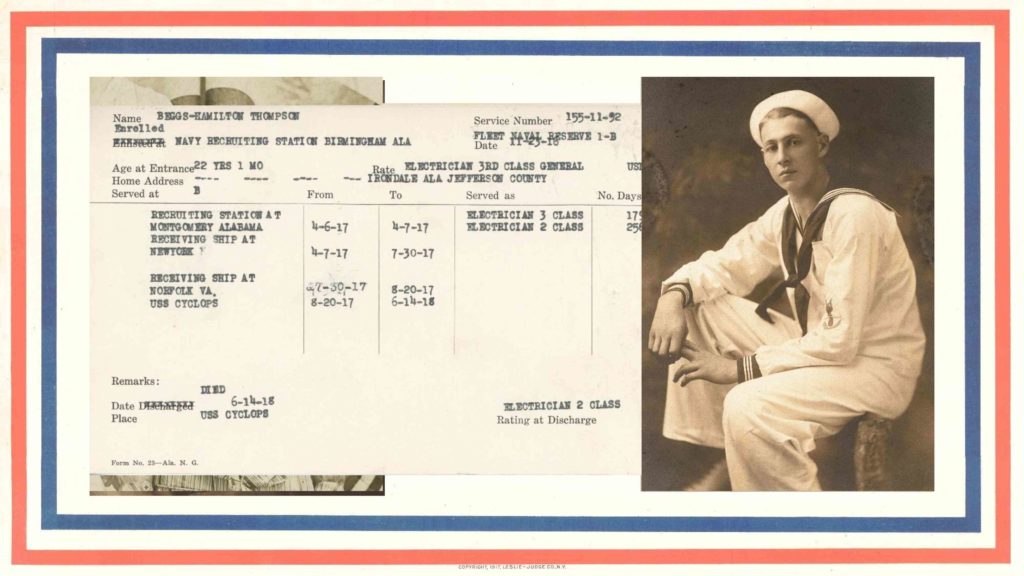

…by far, the most significant addition has been the Alabama World War I Service Records, which are index cards giving details about the men and women from the state who served in some capacity during the war. It’s easy to see why these would jump to the top of our digitization priority list—they offer lots of wonderful information and the timing is perfect—but we were interested in more than just the content. From the start, we saw this as a potential crowdsourced transcription project that would promote community engagement. Because in Alabama, we’re not just commemorating World War I: we’re also celebrating the bicentennial of our state, and a lot of efforts are underway to encourage citizens to connect with their home towns and counties, and to take ownership of their collective pasts. We felt like this would be a great way for people to do that.

So Archives staff and on-site volunteers spent about 18 months digitizing the entire collection—that’s over 111,000 cards. I lost a few volunteers to fatigue along the way, but we got through it. Then, because we wanted the cards to be available throughout the centennial, we decided to add them to our digital collections before doing the transcription project.

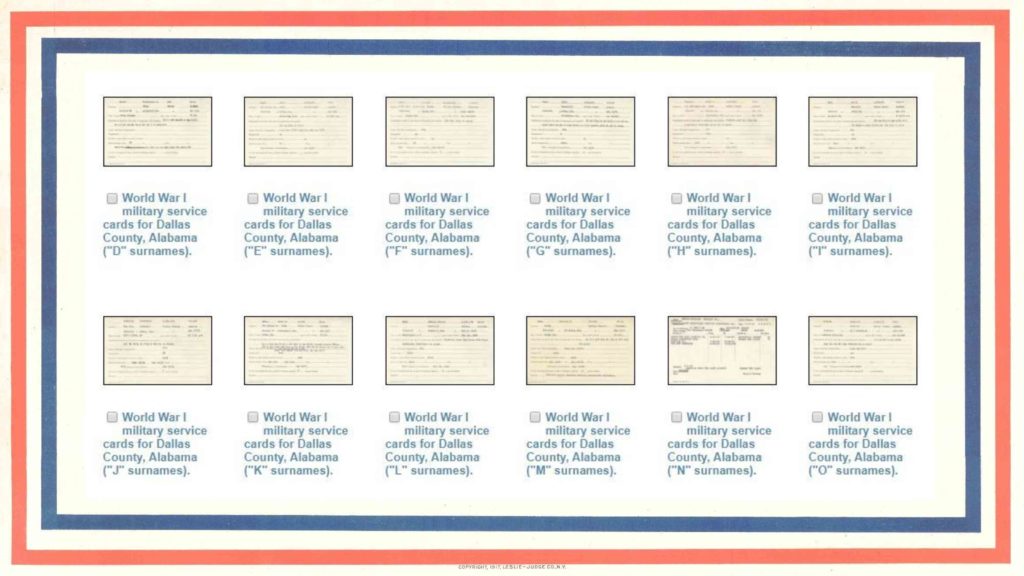

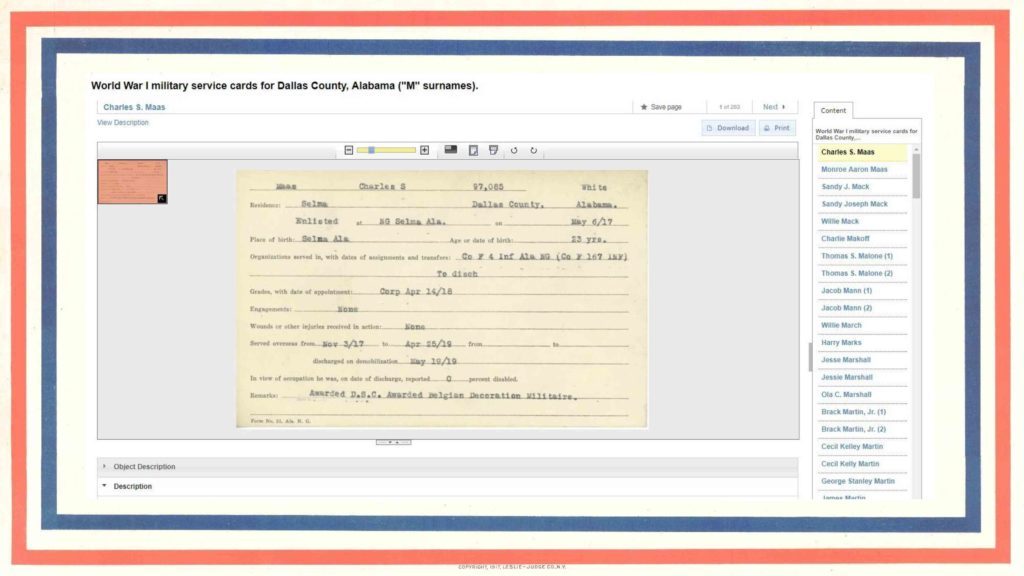

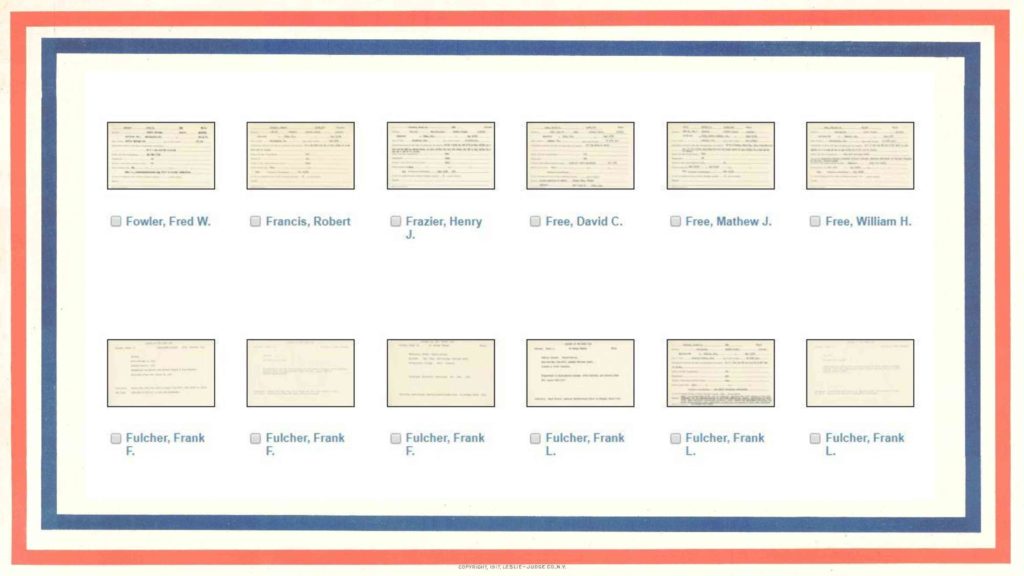

We included only minimal metadata—the person’s name and home county—which we were able to extract automatically from the file names that we assigned each card during scanning. And we uploaded them as compound objects, arranged first by county and then by surname. Here we have the search results for the Dallas County cards, and if we select one…

…we see the cards for the “M” surnames. Along the right side, of course, we have the names listed in alphabetical order, so users can scroll to find the person they’re looking for. This wasn’t a bad way to present the information, but it wasn’t what we wanted in the end. Our goal was to add more details and then upload the cards as single items, so that users would only retrieve results that included the search terms they entered. Again, this isn’t bad, but if you’re looking for James Myers, who is the last name in this set, you don’t want to scroll through 260 cards to get to him.

So we got the cards scanned and we got them into the digital collections, which was very labor intensive, but really, that was the easy part. At this point, we had to figure out how we were going to pull off this grand transcription project we had been telling people about. The Archives has a very small IT staff—we’re down to one person now (and that is not me) and there were only two at this time, neither of whom had the knowledge or experience to design robust system for us, or to modify and implement an open-source option. We were about to proceed with a clunky “solution” using Google forms (which probably would have discouraged participation), but…

…fortunately, we found FromThePage first. This was exactly what we were looking for—a crowdsourced transcription platform that offered hosting services. Now it didn’t seem to be a perfect fit for our specific set of material—we needed a field-based data entry option since the cards are forms—but we contacted the company anyway, to see if we had missed anything.

Ben and Sara Brumfield got in touch with us right away, and said, “No, that feature isn’t available—but we can make it! Let’s have a call.” So we did, and my administration was all in. We put together a plan for the development, which was mostly funded by our auxiliary organization, the Friends of the Alabama Archives. Our director also contacted members of CoSA, the Council of State Archivists, to ask if anyone else might want to contribute to the project, since this could be of benefit to other institutions besides us. And we did get some response—the state archives of Indiana, Virginia, and Missouri all contributed to the work. And now I’ll turn it over to Ben, so he can speak further about FromThePage, this project, and that IIIF integration, which, incidentally, was a happy coincidence for us. We knew nothing about that and had no idea that the Brumfields would be able to integrate the work we had already done in CONTENTdm.

[Ben] FromThePage is a collaborative transcription, translation and indexing application that I started writing as a side project in 2005, to work on a set of family diaries. My great-great grandmother kept diaries from 1915 until her death. Those diaries had been split up among her family members, and I tried to come up with some way to bring them together and to bring family members together through them. The idea of collaborating to transcribe them seemed like the way to do that.

This was just a family project until 2009, when I released the software as open source, and then around 2012, Brumfield Labs started offering a cloud-based hosting option for institutions who don't want to install it on their own servers. Since then there has been a lot of enthusiasm -- it's been used by a number of different institutions for different kinds of material.

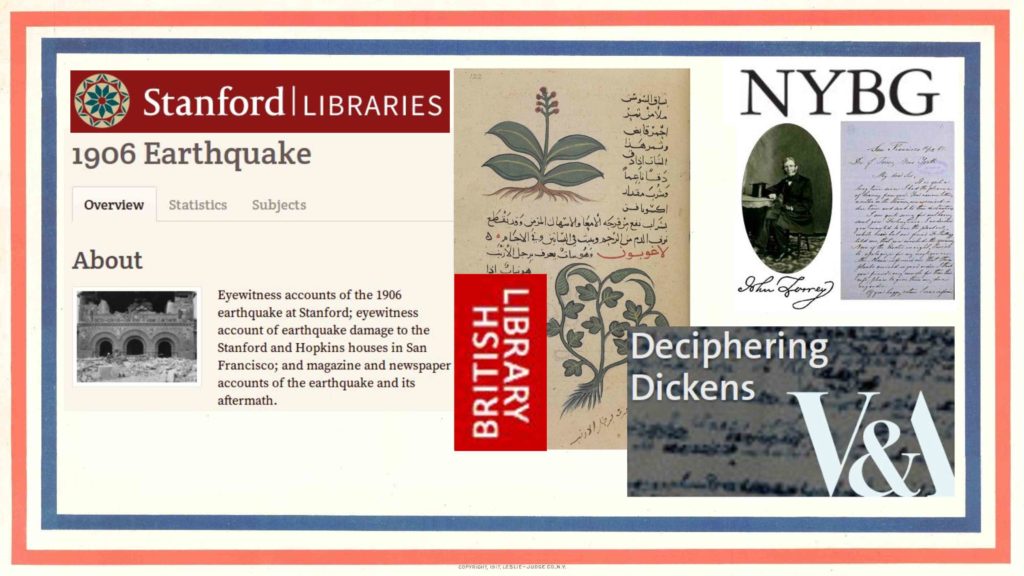

- Stanford University Archives is using the platform to engage alumni to transcribe memoirs of the 1906 earthquake.

- The British Library used the platform for Arabic scientific manuscripts. They got a group of Arabic-speakers and ex-pats together in London to work on texts going back to the eleventh century.

- Also in the scientific world, New York Botanical Gardens is using FromThePage for the papers of John Torrey, an early naturalist, transcribing his letters recording exploration and natural history description.

- Most recently, the Victoria and Albert Museum has used FromThePage to work on some of Charles Dickens's drafts--which are terribly crossed-out--trying to decipher his early attempts at writing Sweeney Todd.

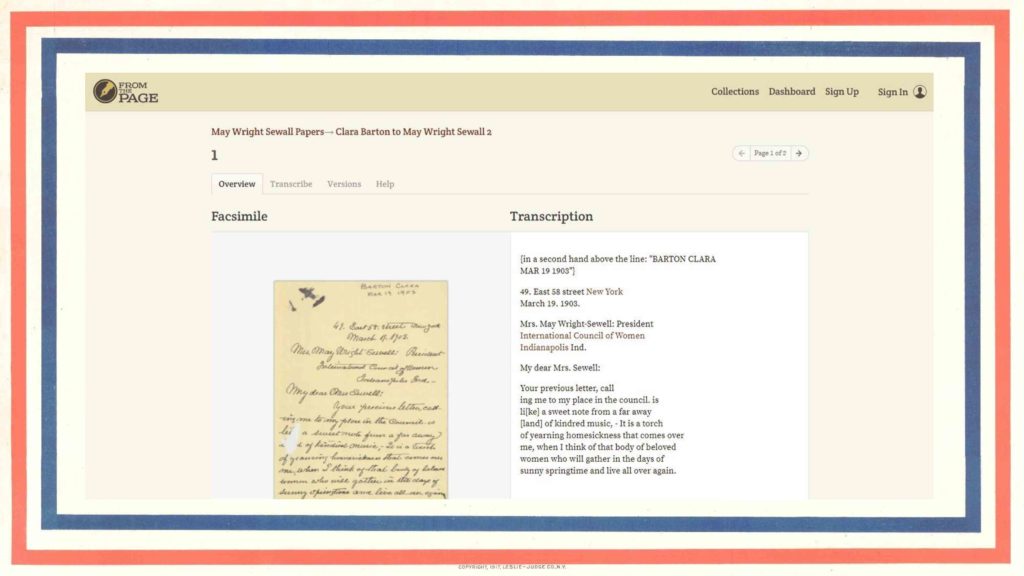

The basic tool is not that different from many other systems. The goal is to keep the experience for the end user as simple as possible, so the transcriber sees a zoomable image on one side of the screen and a place to type what they see on the other side. This example is a letter from the Indianapolis Public Library. (You can see that FromThePage was designed originally for prose text like letters and diaries.)

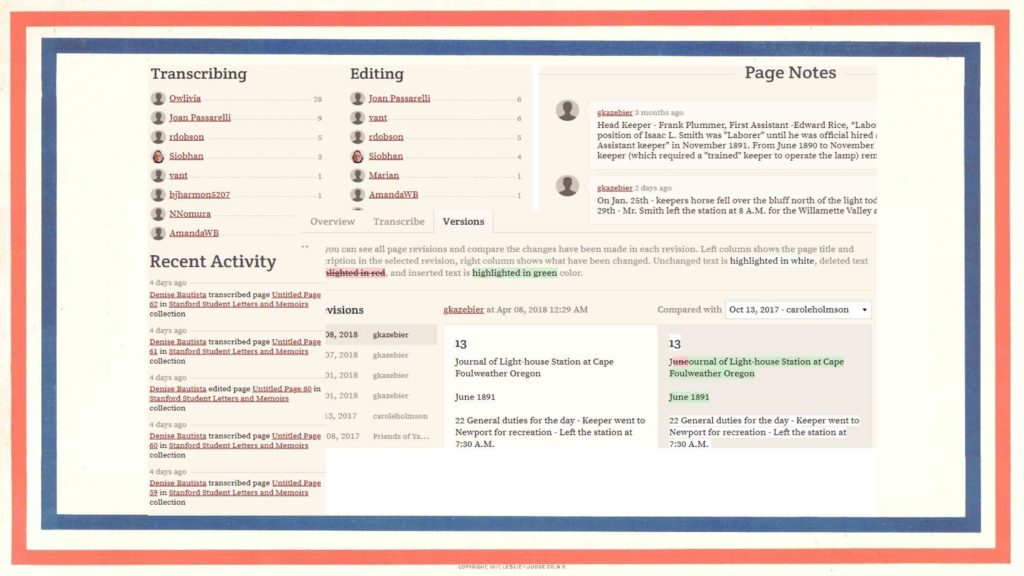

On top of the basic transcription experience, we try to add as much functionality as we can to enable volunteers to be productive and to enable staff members to communicate with the volunteer community and to review their work. For example, we have the ability for people to discuss things that they struggle with on pages; we have an activity stream that lets people see what's going on in their collections, we have some leader boards, and we track every single edit. You can see every change that was made from one version to another of a transcript, with all provenance tracked.

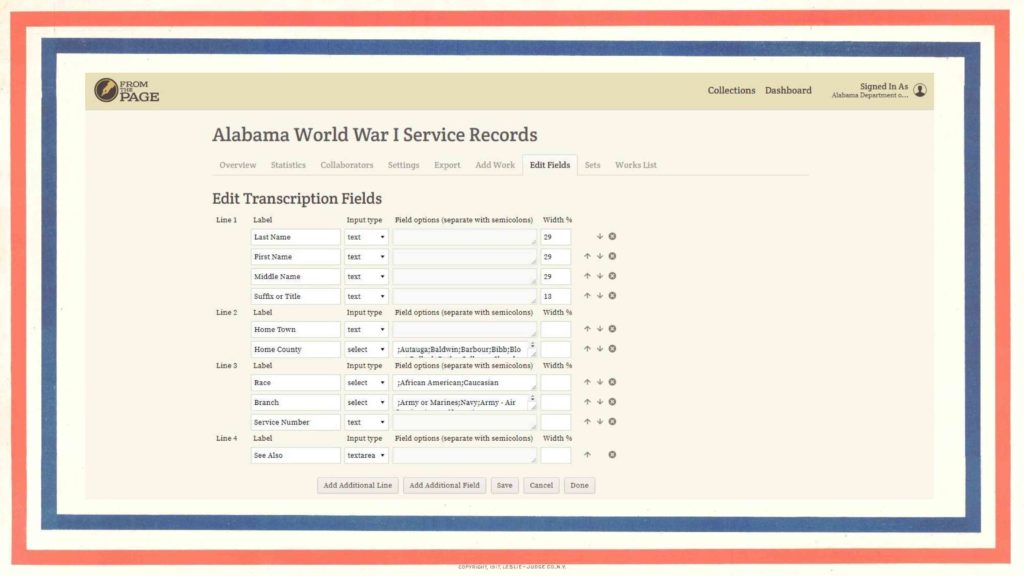

What you don't have, however, is fields. When Meredith and Steve [Murray] contacted us in November, they asked if there was any way we could set up field-based transcription so that the index cards could be brought in from CONTENTdm, transcribed, and then exported.

We created a user interface allowing project managers like Meredith to define fields [to be transcribed]. We also worked with CONTENTdm's IIIF API--we were already active within the IIIF community, so the fact that CONTENTdm supports IIIF means no uploading zipfiles of images or anything like that.

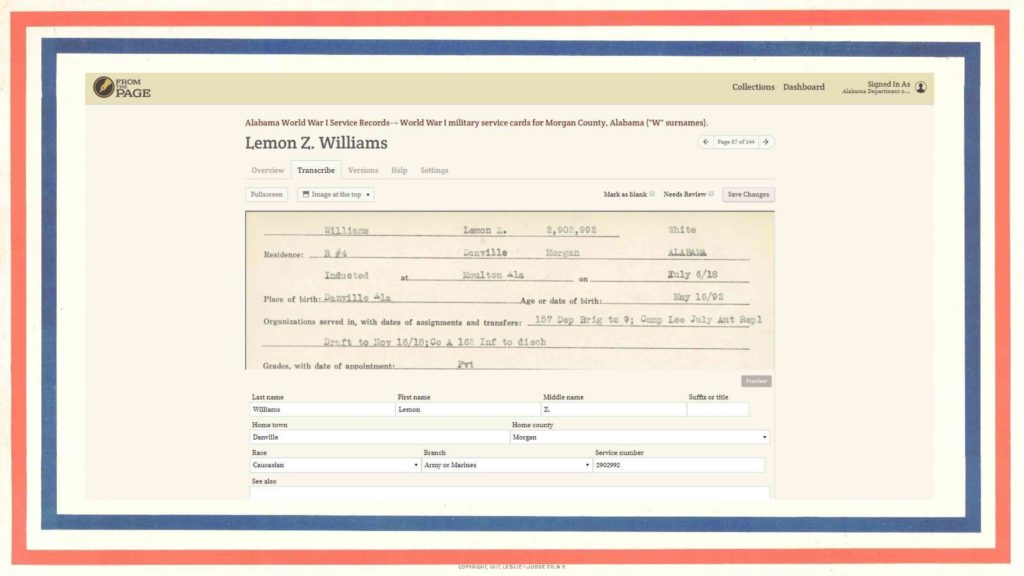

We ended up building this user interface for transcribers, which you'll see is very different from the plaintext transcription option we saw earlier. The user is presented with the same fields that appear on the form, with labels next to each field. We have a small controlled vocabulary for race, or for branch of service, or for home county which is designed by archives staff (primarily Meredith).

[Meredith] We launched the project on April 7 by hosting an on-site training session at the Archives. We invited a number of volunteers who were involved in their local genealogical and historical organizations, because we felt they would be good promoters for us, once they had a chance to try out the software themselves. Between 12 and 15 people attended, which was a great number because everyone was able to get some hands-on experience as well as one-on-one time with the staff who was on hand to answer questions.

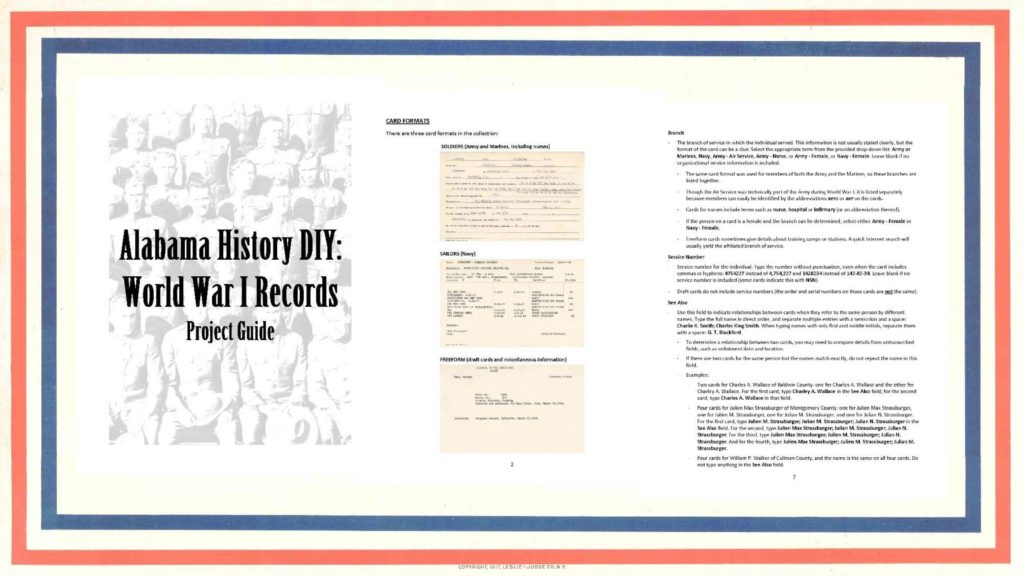

We also debuted our project guide and got some user feedback on that, which allowed us to make modifications before releasing it to the general public. At the end of the day, we fed them lunch, thanked them for coming, and asked them to spread the word—and they did. This was a Saturday, and by Monday my inbox was full of requests to participate. Most of that come from a tweet by the Alabama Genealogical Society, which was retweeted by similar organizations in other states. So a lot of these volunteers were from outside Alabama. The Brumfields told us this would happen, but we didn’t really believe it. We didn’t think other people would care about Alabama records. But really, they didn’t care that they were Alabama records. People are looking for worthwhile projects, and geographic boundaries don’t always matter.

On our end, we promoted the project on social media—primarily Facebook, and we also made a page on our Alabama History DIY website, which supplements are main site. We added a “Virtual Volunteers” heading to the menu (we shamelessly copied that from the Library of Congress because it was succinct and beautifully alliterative) and made a page for the project. As you can see, we asked people to contact me directly because we decided to keep the collection private in FromThePage. We didn’t refuse anyone—I added everyone who gave me a name and an email address—but we wanted that extra level of control. Because of this I have a spreadsheet of all the users and when they were added. Looking at the dates, I can tell whenever there was a post about the collection, because I’d get a slew of requests the next day.

Other than social media and this web page, we really didn’t do a lot of promotion. We had intended to—a press release, at least—but it just wasn’t necessary. And we know it wasn’t because our project was so great—it is a good project, and we’re proud of it, but we benefited a lot from the tie-in to World War I. Also, people are looking for these projects; they want to help with them. And, though it’s trite to say, this demonstrates the power of social media connections in spreading the word.

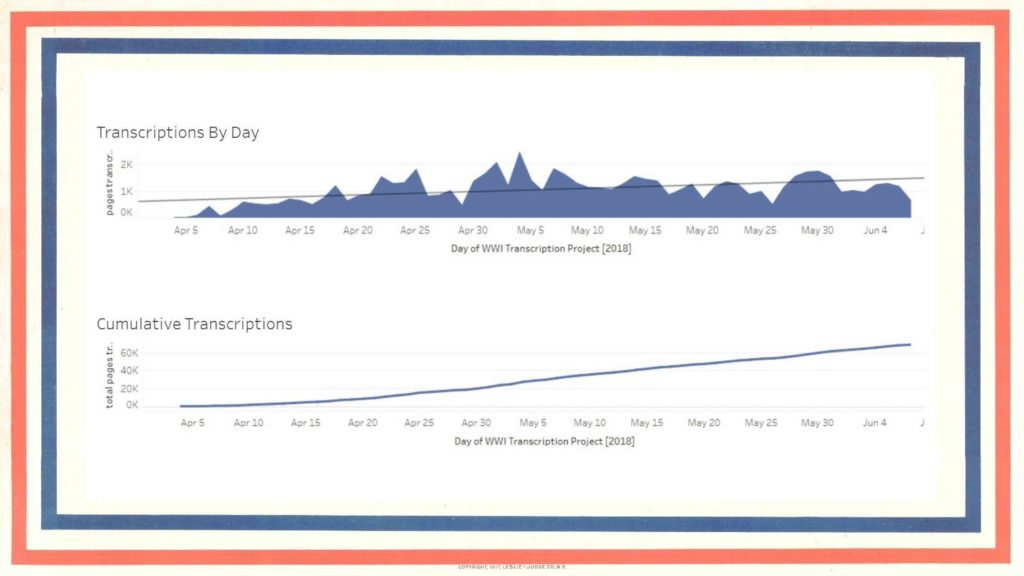

Along the way, the Brumfields kept us informed of the stats they were seeing on their end. In the first 12 days, 10% of the cards had been transcribed. Sara sent the chart you see here about two months after the project launched. It shows that 70,000 cards had been transcribed, and six weeks later (three and a half months after we started) all 111,000 were done. Before we started, we had this unspoken, fingers-crossed target date of November 11, but we didn’t expect to meet the goal, so we were shocked at the success. In fact, back in the spring I wrote an article for the summer issue of Alabama Heritage, which is a quarterly historical magazine. I was writing to recruit volunteers for the new work, which I thought would surely still be underway. By the time it came out, though, everything was finished. So people are contacting me, and I have nothing for them, but I tell them about the next project we’re working on, and promise to contact them as soon as it’s ready.

So, the volunteers have done their bit…

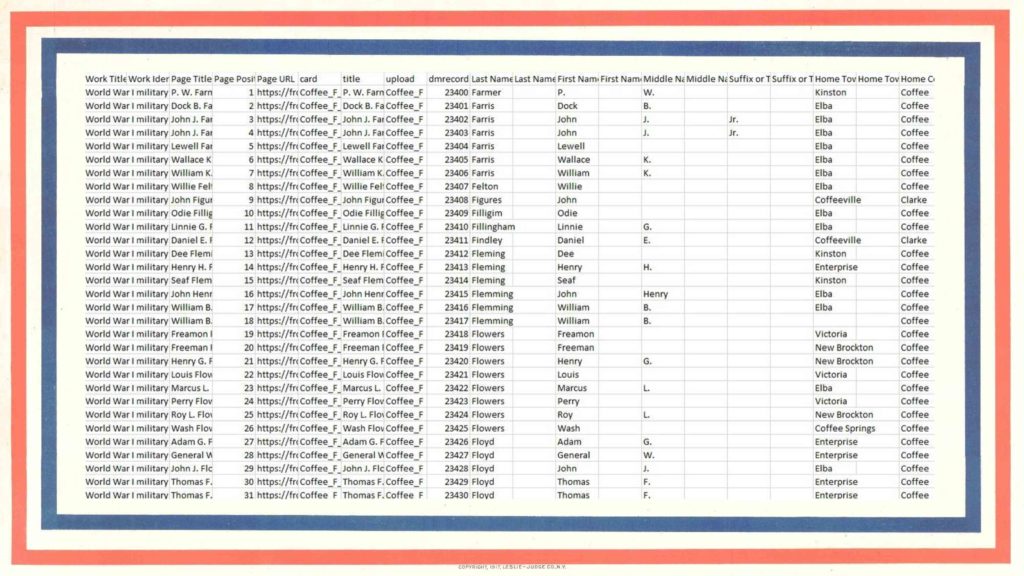

…now it’s time for the Archives staff to get back to work. We export the metadata as CSV files, which we can easily edit-–delete, move, add fields—to prepare for import into CONTENTdm. We’re also doing some metadata checking—not looking at every card, just certain issues we’ve noticed in some of the transcriptions that we’re keeping an eye out for. This stage is slow-going and it will probably be next year before it’s finished, but it’s going well so far.

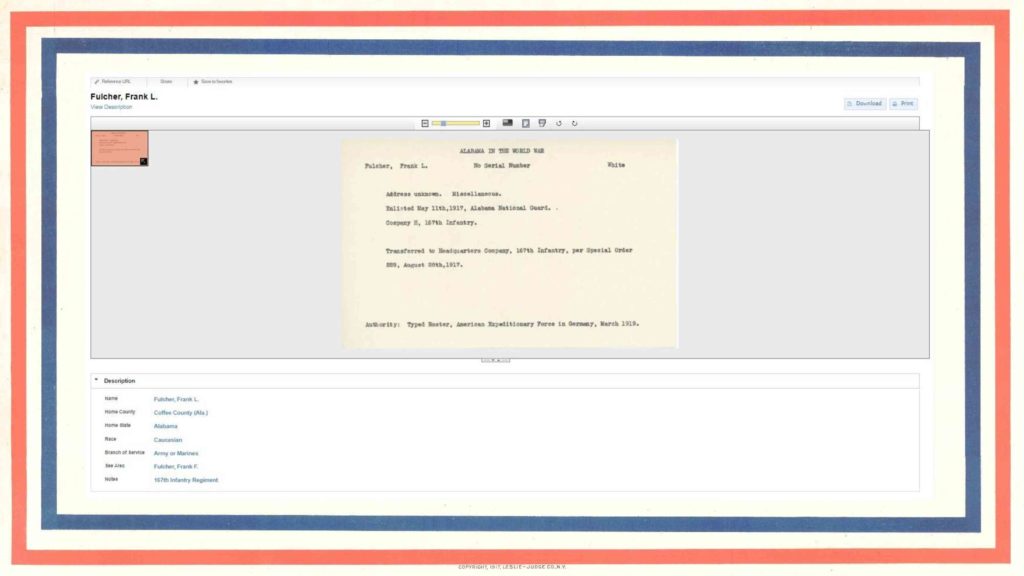

As each new batch of cards is uploaded, I approve them, delete the old corresponding compound object, and then reindex the collection, so there’s never a period when cards are unavailable or duplicated. Here we have search results for Coffee County—just names this time, and if we click on one…

…we see a single card and all the details beneath it, complete with those beautiful hyperlinks and controlled vocabularies. Marvelous—and I can say that in this room and know that you will understand what I mean.

So the outcomes. First, we created a meaningful World War I centennial commemorative program involving the public, just as we’d envisioned from the start. Second, obviously, we accomplished a massive indexing project more quickly than we could have in-house. For most projects that would be the number one outcome, but in this case, that public connection was as important as all the content we gathered. Third, this work resulted in technology that can be adapted for other crowdsourcing projects, and not just ours. Anyone can use the code or the new features in FromThePage. And finally, we established a base of “virtual volunteers” who are ready for the next project, and we formed relationships in a new community of users. This is my favorite point. Our users are the reason we exist. We preserve and share all the wonderful photographs and documents in the world, but if nobody cares, what’s the point. So often we put our content on the web and just hope for the best—we don’t always get to hear back from our users. When we do, it is exceedingly gratifying…

…and for this project, we did hear from our users! These are quotes from volunteers who worked on the card transcription. My favorite is the second one: “I have no ties to Alabama but I feel it is important for all of us to help all of us!” Isn’t that a beautiful sentiment? We should apply that to all areas of our lives, but it fits this project perfectly. First, our volunteers helped us create a better resource for them and other users. And then one state had an idea and several other states helped make it possible. And then one project resulted in these resources that anyone can use. That’s amazing, and it really goes hand-in-hand with the OCLC slogan we were introduced yesterday: “Together we make breakthroughs possible, both big and small.”

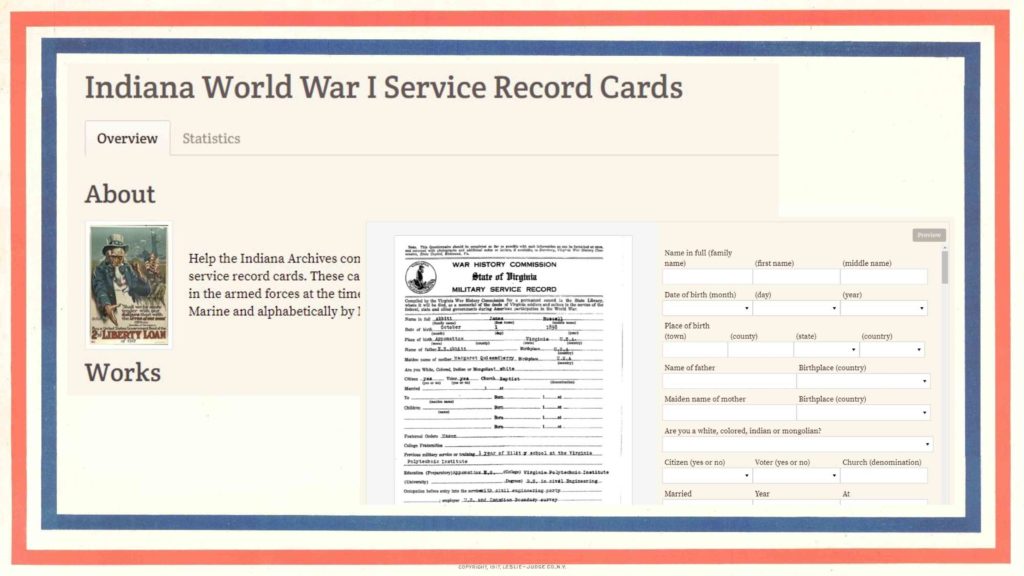

[Ben] So what's next? In terms of "all of us helping all of us", Meredith mentioned that other state archives are involved with this project. Indiana launched a project with very similar service record index cards a little under two months ago. As of this morning, they were up to 21,309 cards transcribed. (I'll bet that if we checked again, that number would go up; they sometimes run at around 100 cards transcribed per hour.)

The Library of Virginia is also working on a similar project, but they have a more complex set of records. They have questionnaires that are multi-page forms, but the work we did for Alabama and CoSA didn't support multi-page forms -- the interface was limited to one record per page. But because the software is open source, Austin Carr at the Library of Virginia has been able to add support for their multi-page forms. (It's still pretty tied to their particular use case, so let's call it a beta, but we were able to roll it out last week.) So now everybody has access to that functionality as well.

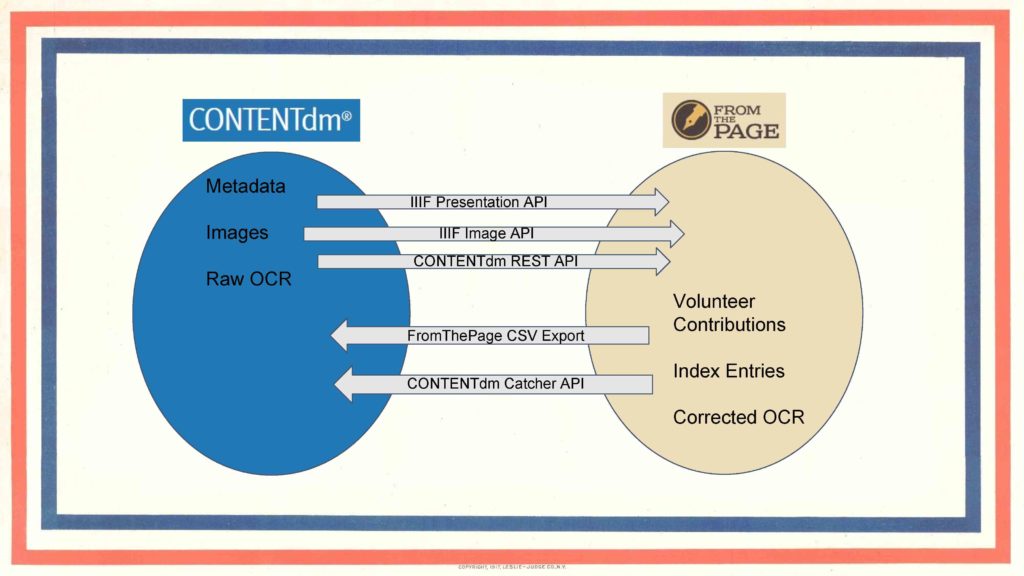

The next technical stage in the Alabama project is--and we have to fit a IIIF slide in somewhere--to do more completion of this loop: the round-trip integration between CONTENTdm on one hand and the crowdsourcing platform on the other. Right now we have an integration that starts with Meredith putting a compound object URL from CONTENTdm into FromThePage. She hits "Import", and that pulls in the IIIF Presentation API representation of that object into FromThePage, displays to the end user the IIIF images, and we also hit the CONTENTdm REST API to pull out the CONTENTdm metadata for that object.

What's the next step? Right now, Meredith is pulling out a CSV representation of the transcripts to re-index in CONTENTdm. But one of the additional things that ADAH funded the development of was an OCR correction module so that we can bring raw OCR directly from CONTENTdm into FromThePage, corrections can happen there, and once they're reviewed, Meredith can push "Synchronize to CONTENTdm", enter her CONTENTdm credentials, and then FromThepage will use the Catcher API to update the metadata with the corrected OCR.

CONTENTdm integration & field based transcription in FromThePage were funded by the Council of State Archivists led by the Alabama Department of Archives and History, and joined by the Indiana Archives and Records Administrations, the Library of Virginia, and the Missouri State Archives. These enhancements are available to all users of the open-source crowdsourcing platform, whether hosted independently or on FromThePage.com. To learn more, contact support@fromthepage.com or sign up for a trial account.