On June 8, 2017, Patrick Cuba, John Howard, Peter Robinson, Jeffrey Witt and I organized a discussion session for the IIIF conference hosted by the Vatican Library. We wanted to explore our efforts to utilize IIIF in our existing, manuscript-based textual projects, from crowdsourced transcription to documentary editing to textual scholarship. The urgency of this conversation was heightened during the weeks between our proposal and the conference itself, as a new Text Granularity Working Group was formed by members of the IIIF Newspapers Working Group.

For our session, each of us presented a 5-10 minute lightning talk describing our experiences and making a concrete proposal to move the community forward. Karen Estlund, organizer of the Newspapers and Text Granularity working groups, also presented on those group's ideas for text and IIIF -- a generous act given very short notice. A general discussion followed the lightning talks.

This is a rough reconstruction of the text of my talk.

Those of us trying to work with text and IIIF have a problem.

The examples we are offered to work from barely represent text at all!

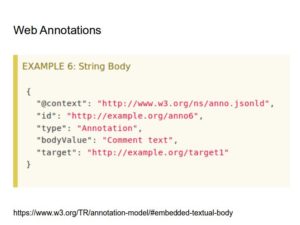

Here is one example from the Web Annotation Spec: the text represented is a plain-text string consisting of only two words: "Comment text".

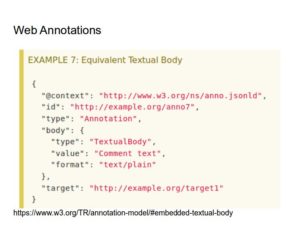

Here's the same example as a "Textual Body". It's a slightly more sophisticated structure, until you get to the text itself, which is still only two words. This is really an impoverished vision of what text is.

However, we're not the only ones with this challenge.

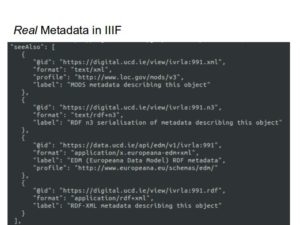

The IIIF Presentation API spec also gives examples for embedding metadata within IIIF manifests. It's possible to take your existing metadata from other systems and serialize all of it out to a JSON-LD format within your manifests.

However, nobody's doing that anymore! What libraries are actually doing is linking to their descriptive metadata in other systems, where it is stored in formats like MODS which are actually designed to encode metadata.

I think we should explore this model of linking to our text in the formats we already have, rather than attempting to embed it as annotations.

So how can we link from IIIF to texts?

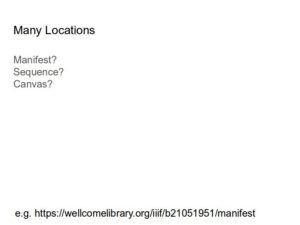

We have a lot of options. Manifests can contain seeAlso or service elements linking elsewhere. Sequences can contain a rendering that links to a text like a PDF. Finally, of course, we have open annotations.

We also have many options on where to place those links. Does it make sense to link at the manifest level, the sequence level, the canvas level, or each of these?

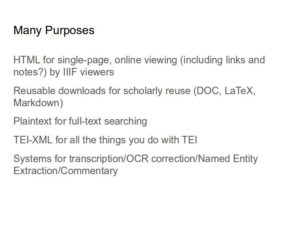

Most importantly, links to our texts serve many purposes.

There's the sweet-spot for annotations, displaying a simple transcript of a page or region of a page for display by a viewer.

However, there are many more use cases:

- Downloads of texts in reusable formats like Microsoft Word or LaTeX so that scholars can include texts within their articles.

- Plaintext that library systems can ingest for full-text search.

- TEI for, well, all the things you can do with TEI.

Finally, we need to link from IIIF to services to create or enhance text via transcription, translation, or named entity identification.

It's not enough to define best practices for linking from IIIF to texts. We also need to figure out how to link from our texts to IIIF images.

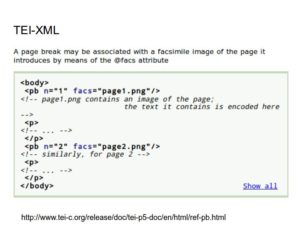

The TEI Guidelines provide a facs attribute on the page break element that lets editors link to page images. However, there is no guidance for linking to IIIF image services.

My proposal for connecting text and IIIF is that we follow the example of the Newspapers Group, and create fixtures--well documented, machine-readable exemplars--of linking between text and IIIF using terminology familiar to textual editors. We start with a small number of short documents (a two-page letter might be perfect here), at varying levels of encoding, and create a set of files encoding those documents in both IIIF/WebAnnotations and TEI.

We define use cases for these fixtures that will let us test both the IIIF sweet spot (like single-page transcripts within Mirador) and a simple TEI viewer like EVT that is agnostic of IIIF.

I also propose that we postpone a couple of important things.

We should start with small, simple, single-document/single-text works until we get a consensus on how those should be encoded. Only then do we move on to multi-document texts and multi-text documents.

More controversially, I also think we should just postpone the big question of how we model texts as annotations. At the moment, this seems too huge and ill-defined to grapple with, but we may find that if we focus on linking first, some use cases may emerge that are obvious fits for embedding our texts as annotations.

The discussion following the presentations was productive, but also revealed some real divides among the participants. Those of us (like myself) with a background in editing are having a lot of trouble mapping our concepts to Linked Data, or indeed in seeing the benefit to trying. Meanwhile, some participants from the library world appeared not to be aware of the 30-year history of textual encoding practice represented by the TEI and the community that created it. Only continued conversation between and within these communities will fix this situation.

My own presentation was only one of six, so I will link to the others from this post as they become available.

If you are interested in exploring these issues--whether to help develop the fixtures I propose, or to tell me I'm wrong--send me an email at benwbrum@gmail.com and I'll try to include you in the conversation as it develops.