We're often asked about the quality of crowdsourced transcription projects by people skeptical that amateurs can edit historic documents. Of course we're confident that amateurs can do high-quality work--especially in active collaboration with professionals--or else we wouldn't be doing this. But many questions remain.

What is "quality"?

While writing the first draft of the quality control section of The Collective Wisdom Handbook, Austin Mast and I spent a lot of time discussing the different dimensions of quality. Austin divides what we think of as "quality" into fidelity and accuracy, which the Handbook differentiates this way:

Fidelity is the digital representation of an object following project guidelines. A transcription project might ask the participant to type the letters as written in the image of a page or label. If the page reads “30 m east from the wharf” and the contributor types out “30 meters east from the wharf” or “20 m east from the wharf,” both would represent reduced fidelity. [...] Accuracy is correspondence with generally agreed-upon reality.

Fidelity and accuracy often conflict in transcription projects: if a name is misspelled, a "faithful" transcription reproduces the spelling, but an "accurate" transcription corrects it.

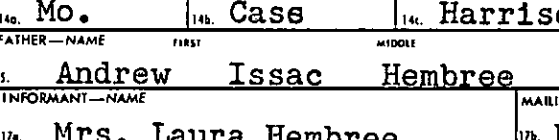

The overwhelming practice among transcription projects is to value fidelity to a document over accuracy. If a genealogist complains that an original record misspelled their ancestor's name, the record will very rarely be updated. Most people running online databases consider them indexes to records, rather than indexes to people. Prioritizing fidelity gives a clear way to judge arguments; if one researcher insists a historical persons middle name was "Tyler" while another insists the name was "Terry", the archivist need not arbitrate between them, but can transcribe the name as written. In the example above, it's possible that "Issac" was an error typing the name "Isaac", but "Issac" is also a real name. Without other knowledge about Andrew Hembree's middle-name, a strict policy of fidelity to the document keeps us from guessing.

"Type words exactly as they are written in the document. This includes capitalization, abbreviations, names, dates, and even misspelled words. If you happen to find a misspelled name, place, or event within the record, we encourage you to add a tag or a comment with the correct spelling of the word. This will ensure that the record is returned in a search result for that person, place, or event." —Transcription Tips, Citizen Archivist Dashboard.

Fidelity versus usability

The problem with strict "type what you see" policies is that they may produce high-fidelity results that are unusable. This is especially apparent when transcribing text that has a limited number of accurate answers, like place names in vital records or census forms. The value of preserving variant spellings of names of counties, provinces, or states seems limited (outside of toponym history projects), and might even be counterproductive. If the goal of a project is to create a database of records segmented by county, variant county names will need to be reconciled against a controlled vocabulary before the segmentation takes place. If this effort is postponed until after documents are transcribed and exported, staff doing the reconciliation may not have the context of the original images.

In practice, most indexing projects prioritize accuracy for some fields--using drop-down select lists for place names or other controlled vocabularies--but prioritize fidelity for others by asking users to type exactly what they see. It's a balancing act that ensures high-quality transcriptions that are also usable, and lets the person who is looking at a document image reconcile what is written to standard forms.

"Unless the project instructions and field help say otherwise (and they often do!), correct misspellings of place-names. However, this general rule does not apply to the spelling of personal names. Since it is difficult to know whether a person's name is actually misspelled, you should typically index a person's name as it appears on the record." —How should I index incorrect records?, FamilySearch Indexing.

Among projects hosted on FromThePage, we tend to see documentary editions and research libraries prioritize fidelity in full-text transcription projects. State archivists and quantitative researchers tend to prioritize usability in field-based or spreadsheet projects. Each project finds a balance, and there is no single right answer.