Sara spoke last night at the inaugural Rice Computer Science in Austin Meetup about our work. Here is a rough transcription of her talk.

I know Carlyn billed me as an entrepreneur, and I am, but I thought for this crowd it would be more fun to talk about the work, rather than the business. If you want to talk business, I'm happy to do that afterwards.

First, a couple of questions for y'all. We're all here because we have computer science degrees from Rice, but I'm curious -- with a show of hands -- how many of you had a second major in addition to CS? 2nd major was in the humanities? (note: There were about 5 out of a room of 30.)

When you study more than one thing, it makes you broader. Interdisciplinary thinking gives you more models of how the world works. 20 years ago, at Rice, it wasn't that unusual to find double majors across engineering and the humanities. My own second major was in the Study of Women and Gender -- interdisciplinary itself -- and the models it gave me were how to "think outside the box". Ben, my partner -- wave Ben -- his 2nd major was linguistics, which means he thinks in deep and structured ways about language, text, representation.

I know you're thinking "what does this have to do with anything?" We've built a business combining computer science with the humanities. The field is called Digital Humanities, we are Brumfield Labs, and I'm going to share some stories about what we do.

1) Story 1 -- Sentiment analysis and the Digital Austin Papers.

These are the papers of Stephen F. Austin, widely considered the father of Texas; it's a project we work on with a historian at UNT.

We wanted to apply sentiment analysis to the Digital Austin Papers. In case you don't know how sentiment analysis works, simple sentiment analysis works by scoring every word in a document against a dictionary. A word is positive, neutral, or negative. One of our questions was whether modern sentiment analysis dictionaries -- which are largely based on product reviews and social media -- would even work on 19th century documents. So we scored all these documents and then we spot checked them by looking at the most negative document (slide change)

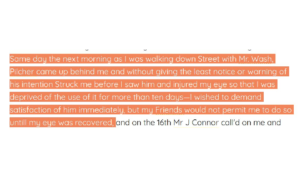

The most negative document described a feud, altercation, and duel between Stephen F. Austin and Joshua Pilcher.

"the next morning as I was walking down Street with Mr. Wash, Pilcher came up behind me and without giving the least notice or warning of his intention Struck me before I saw him and injured my eye so that I was deprived of the use of it for more than ten days—I wished to demand satisfaction of him immediately, but my Friends would not permit me to do so until my eye was recovered, "

He sucker punched him!! And Stephen F was furious! "demand satisfaction" here means "challenge him to a duel"! I think that qualifies as pretty negative, and definitely has strong emotion.

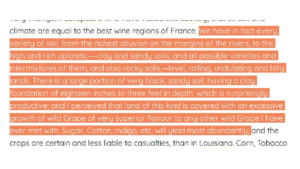

The most positive, by contrast, was Austin's glowing sales letter to a Swiss group considering immigration to Texas.

We have in fact every variety of soil, from the richest alluvion on the margins of the rivers, to the high and rich uplands;—-clay and sandy soils, and all possible varieties and intermixtures of them, and also rocky soils,—level, rolling, undulating and hilly lands. There is a large portion of very black, sandy soil, having a clay foundation of eighteen inches to three feet in depth, which is surprisingly productive; and I perceived that land of this kind is covered with an excessive growth of wild Grape of very superior flavour to any other wild Grape I have ever met with. Sugar, Cotton, Indigo, etc, will yield most abundantly;

"Biggest and grandest," huh? If you ever wondered where Texas's high self regard came from, I'd say it was present from the beginning. And again, this seems like a strong positive sentiment.

Ok. So it seems to work, but does it help historians? SFA's colony in Texas was entirely dependent on cotton plantations, the "problem" is that the Mexican constitution outlawed slavery, but they weren't very serious about it, and let Austin's colonists pass with a wink and a nod, until 1830 when Mexico got serious about abolition. So what do we see in Austin's papers?

Here's a graph of the Austin papers that mention slavery, graphed over time, and colored by sentiment... and what happens in 1830? Austin and his correspondents freak out. (And if you grew up in Texas, you know what happened 5 years later...)

Story 2

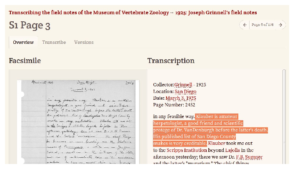

Our core product -- the one we built our business around -- is FromThePage, a collaborative manuscript transcription platform. Libraries, museums, academics post their handwritten historical documents online, and volunteers come and help transcribe them. From a technical perspective, FromThePage is not particularly interesting. What is interesting:

-- The content -- historical documents ranging from lighthouse logs, plantation store ledgers, legal rulings from the crusades, letters of Stanford students about the 1906 San Francisco earthquake

-- The work it enables -- very deep immersive reading of historical documents

-- The challenges we work with -- finding, recruiting, and motivating volunteers.

The most charming parts of our work is around discovery and serendipity.

One of our earliest transcription projects was the field books of Lawrence Klauber, a preeminent herpetologist in California in the early 1900s-- an expert on rattlesnakes.

A year or two later, we were working with the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at Berkeley on another set of naturalist field books, these of Joseph Grinnell, a ornithologist. Not a big deal, except these two projects, a hundred years after they were written, both mentioned meeting each other on the same day!

Klauber is amateur

herpetologist, a good friend and scientific

protege of Dr. VanDenburgh before the latter's death.

His published list of San Diego County

snakes is very creditable.

It's pretty neat that they met, even if Grinnell is a bit of an academic snob. Seeing this community of scientists, 100 years later, in what's the first transcription of these field books, is exciting.

Another story is of a guy who was doing a vanity search of his name -- "Nat Wooding" -- and stumbled across our very first collection of material, the diaries of a tobacco farm in rural Virginia. The searcher's name was Nat Wooding, and, it turned out, the name of the diarist's mailman was also Nat Wooding. Coincidence? Nope. The mailman was Nat Wooding's great uncle and namesake.

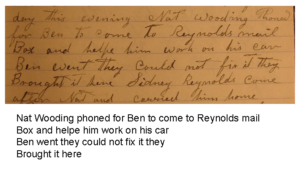

Here we have one of those pages that mention Nat Wooding -- turns out he's always having trouble with his car, which is a problem if you're the mailman:

Nat Wooding phoned for Ben to come to Reynolds mail

Box and helpe him work on his car

Ben went they could not fix it they

Brought it here

Nat -- the modern Nat -- went on to transcribe tons of material on that project, added a lot of value by knowing the people and places mentioned, and when it was done asked for more. We didn't have any more Virginia farm diaries, so we asked if he'd be interested in the previously mentioned ornithology fieldbooks. Nat's response "I've never done birds before, but I spent my entire career as a statistician analyzing environmental impact fish populations. I can probably do birds." Nat went on to contribute both transcriptions and a structured way of thinking about species names in those transcriptions to the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, and has since gone on to many other transcription projects.

This ability to reach across time -- and to really engage with it -- is what motivates our volunteers and what differentiates us from many of the other transcription projects out there.

Story 3

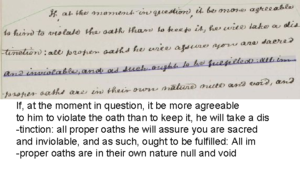

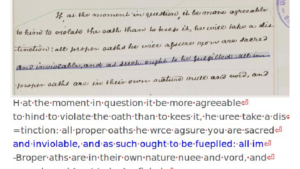

One of the most exciting areas for all of computer science these days is machine learning, and that's true for us as well. When you work with handwritten texts, people -- amazingly -- always ask "can't you OCR that?" For years, we've said "no", but we're collaborating with a project out of the EU called Transkribus that is trying to do just that -- Handwritten Text Recognition. The Transkribus platfrom needs a training corpus -- hundreds of handwritten documents, ideally in the same hand, already transcribed. Even with that, the models only achieve 95% character accuracy rate. 95% character accuracy sounds awesome, but...

-- this is a page that's been manually transcribed. (read text)

-- this is the same page transcribed with HTR. (try to read text)

You would never put the second transcription in front of your library patrons, it wouldn't be useful to researchers, and it definitely isn't accessible.

A 95% character accuracy rate means your word accuracy rate is about 6 words out of 10.

So we're asking questions like "what can we do" with 6 good words out of 10. Our ideas are to use this HTR'd material to enhance discoverability, so say, run sentiment analysis over the dirty HTR and identify the documents with the strongest sentiments and surface those as interesting enough to transcribe. Other ideas involve using a technique called TF-IDF to identify the unique keywords in a corpus. TF-IDF stands for term frequency / inverse document frequency -- so you take the most common words in the entire corpus of documents, and you compare the most frequent words in a particular document to see if the document "stands out" from the rest -- does it have different keywords than the rest of the documents in the corpus? The project we're hoping to apply this too -- if funded -- are the papers of an early logistician -- Charles Peirce -- whose papers are so out of order it's like someone threw them all in the air and gathered them up again. Anything we can do to help surface particular words and strong sentiments in the text will lead researchers to more interesting pages to work with.

So -- that's our little corner of digital humanities. We didn't walk out of Rice doing this -- we had very traditional jobs for years, then started FromThePage as an open source project, then worked with customers on nights and weekends, then split our time between part time work and the business, and only recently has it become our full time gig.

Thanks for inviting me speak today, and I'll be around after the speakers for questions or conversation.

If you have any digital humanities projects that need advice or programming, please drop us a line at support@fromthepage.com.