Last September, Ben and Sara Brumfield hosted a webinar on your first crowdsourcing project. The presentation, linked below in a video and embedded as slides, covers selecting material, finding volunteers, developing transcription conventions, keeping volunteers engaged, and what to do with your transcriptions once you're done. You can sign up for future webinars here.

Read through Ben and Sara's presentation:

This is Sara Brumfield with FromThePage. I’m here today with Ben, my partner, and we wanted to tell y’all what we’ve learned over a decade of running crowdsourcing projects.

Sara and I run a platform for crowdsourcing manuscript transcription and OCR correction called FromThePage. There’s a number of different crowdsourcing tasks out there, we really focus on crowdsourcing around archival documents and special collections, specifically textual records. But we think that the lessons we’ve learned applied to other kinds of crowdsourcing tasks like georectifying maps and photo identification.

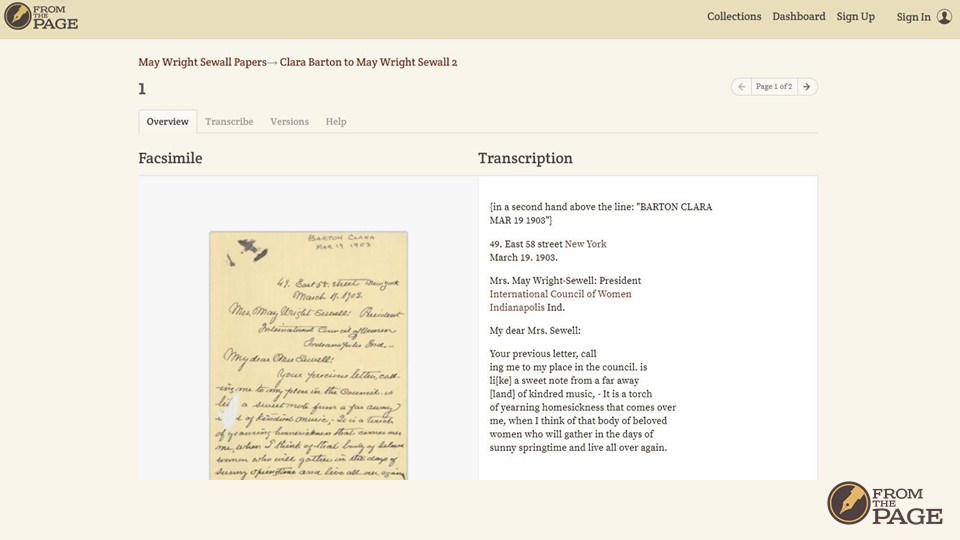

In brief, our platform allows people to see an image of a page and to transcribe the text from that page. We try to keep things as simple as possible for the users, because frankly, transcribing text is hard enough.

We’ve seen a lot of successful projects over the last few years. Here’s a handful of our clients.

Effective Crowdsourcing is really a collaboration between the institution and the public. The goal is deep public engagement with special collections and archives.

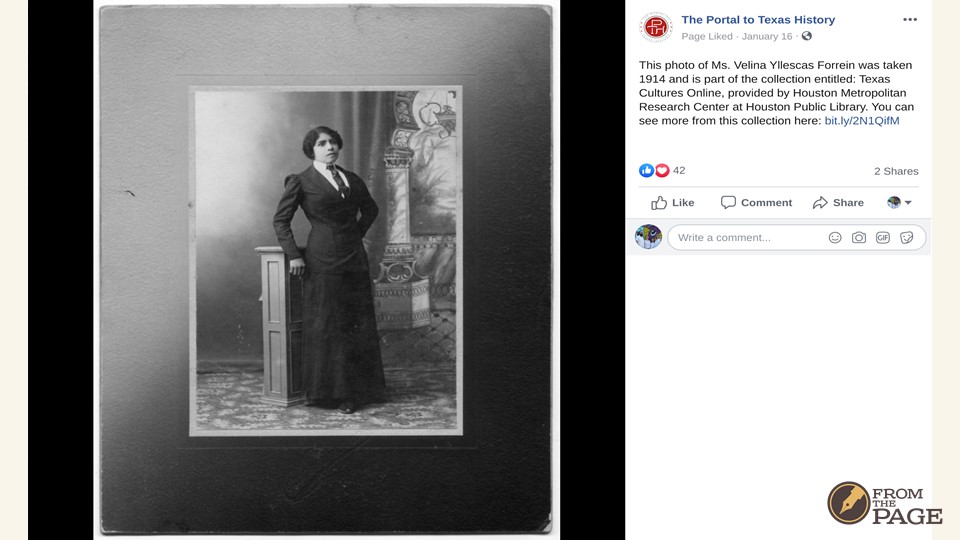

When I say “deep engagement”; many organizations these days have social media presence and instagram accounts and that allows them to expose their material more broadly to the public, which is wonderful, but one of the challenges is that often the only way the public can engage with that material is by clicking a like button. Which is great for statistics, but it’s not really deep. It’s not really immersive and it doesn’t allow them to share their passion about the material and the subject matter or about you and your institution back with the institutions sharing the content.

Crowdsourcing, in addition to be about engagement is about improving metadata for digitized assets in ways that require massive amounts of human interpretation. And that doesn’t mean necessarily massive numbers of humans or massive numbers of items; it could just mean one person whose really passionate who’s willing to spend a lot of time transcribing a single set of letters or a single diary. But that’s the kind of thing that archival staff usually aren’t able to commit their resources or their organizational priorities to that kind of interpretation.

Speaking of archival staff, effective crowdsourcing is only possible with the guidance of and engagement of archives staff. You can’t replace staff members and trained information professionals with the crowd. That just doesn’t work.

We have a cute picture of a puppy here because we have a standing joke. Crowdsourcing is not “free as in speech” or “free as in beer”, it’s “free as in puppy”

The puppy is free, but you have to take care of it; you have to do a lot of work. Because volunteers that are participating in these things don’t like being ignored. They don’t like having their work lost. They’re doing something that they feel is meaningful and engaging with you, therefore you need to make sure their work is meaningful and engage with them.

So we’re going to talk a lot about the work that goes into successful crowdsourcing projects.

So let’s start with volunteers because if you don't have volunteers, you aren’t going to have a successful crowdsourcing project. Period. Right?

This is a picture of some of the Library of Virginia’s volunteers.

So you need to start by thinking “Where can we find volunteers?”

Who will they be? Do you already have volunteers who work with your institutions? Do you have people who are local who are interested -- maybe you have local material at your local history societies or your local genealogists would be interested in work with. Maybe you’re deep on a particular subject matter and you can reach out to communities around the subject matter; so for instance we did an early project with the Yaquina Head Lighthouses they had lighthouse keepers logs over decades, and they were able to engage with lighthouse fans. Turns out there people who are really enthusiastic about lighthouses, and have those people virtually come in and work on transcribing.

So when you think about volunteers, you can also think about what material has been most popular with your patrons. And think about why it’s popular. The last thing to realize is that crowdsourcing is something your not familar with, but it’s not something your volunteers will be familar with. It’s a bit intimidating, right? So if you think through how you can make it easier for them, that puts you in a good mindset for working with your volunteers.

When you run projects on FromThePage we also send out a monthly newsletter that features new projects. If you want us to include yours, we can. And what we see….

Is that volunteers and transcribers get really into this type of work. It is fun, it is very engaging.

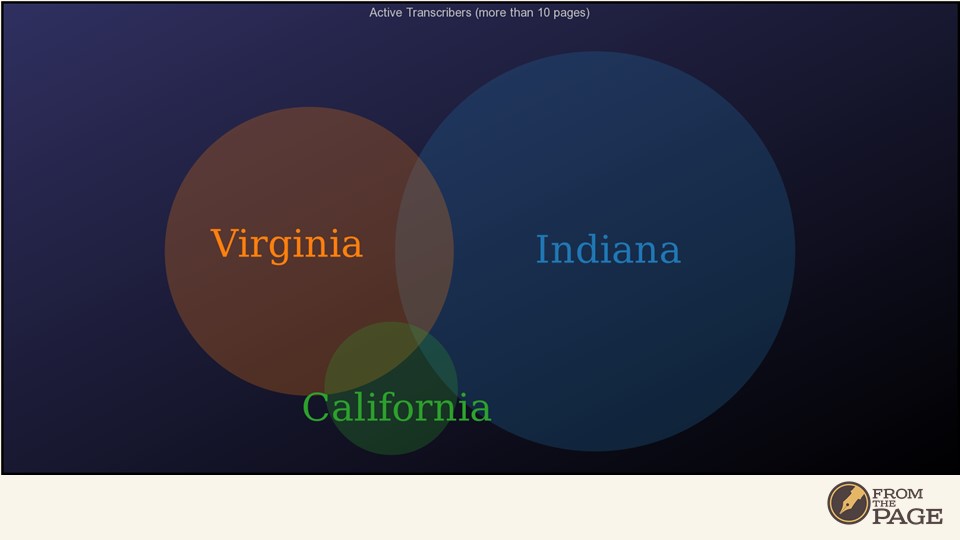

The image on the screen is represents the most active transcribers on three different projects -- the Indiana Archives, the Library of Virginia, and the California State Library. What you see here is that--while the bulk of their most active transcribers were independent, there were overlaps. So there are volunteers who go from project to project.

We have one volunteer who, about once a month, will scroll through our list of projects looking for something she hasn’t worked on, and go hop in and try something new. It’s fascinating--sometimes she finds something she’s really interested in and goes deep and contributes a lot, and sometimes she does a page or two and moves on.

How do you figure out what material is appropriate for a crowdsourcing project?

Success comes in many forms and volunteers are motivated by a number of different things. Not every volunteer is motivated by the same thing.

The things that we tend to look for are material that can tell good stories, by which we mean that if you get started reading it, you really want to turn the page and find out what happens next. Letters and diaries have great intrinsic motivation for people to keep transcribing and keep coming back to them because they want to know what happens next. They get involved in the story and feel good about contributing to it. That provides an immersive experience for them as well.

Not everything that is immersive need necessarily be text--we’ve seen immersive experiences from world war one service cards as the experience of going through different cards for individual service members to see where they enlisted, how old they were, what branch they were in and where they fought can be really highly immersive as you are taken back to 1918.

Similarly, you can be successful with material that has a lot of local history. The Indianapolis Public LIbrary is running a project transcribing records from Indianapolis public schools. These don’t have a lot of great stories behind them that I can see, but they have a lot of local history of importance to genealogists who themselves have had the experience of benefiting from these kinds of digitized records and are keen to contribute back. Lists of parents and children in these school records are really gold for genealogists, and the volunteers understand that.

We also find that if you can give your volunteers a sense of accomplishment, that’s very motivating. I think we’re all motivated by checking things off of a list so some of the WW1 Service Card projects were very successful . I think part of it was that you had a single cards--Alabama Department of Archives and History was the first FromThePage project to do this…..--a single card, and they only collected about five fields from each card, so a transcriber could get a lot done. We all like to get stuff done, and that feeling of accomplishment kept them coming back.

Alabama Department of Archives and History’s project was 111 thousand WWI service cards, and they transcribed them all in two and a half months. Because their material hit so many of these points, and because they had such great relationships with their local genealogy and history organizations.

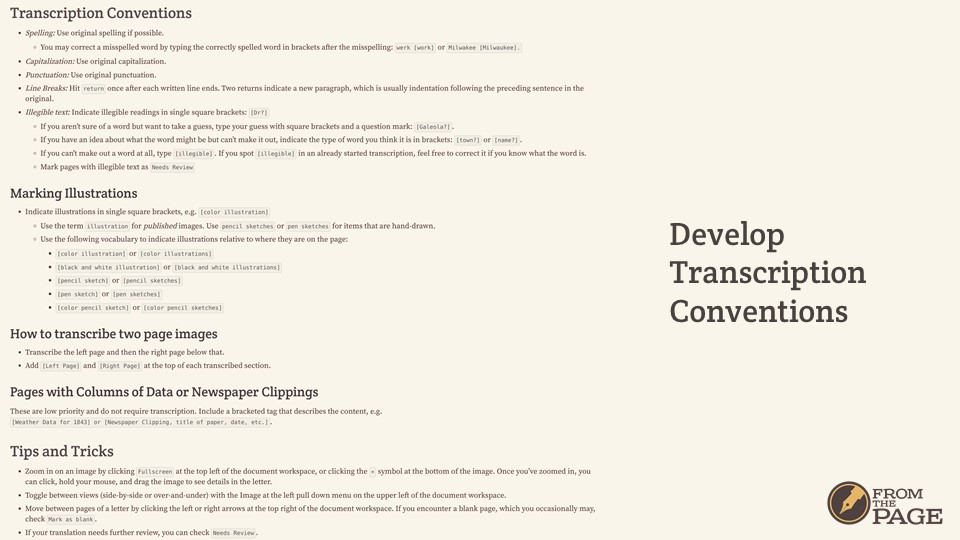

Once you’ve identified the material, the next thing to do is to define the task. For transcription projects, that means giving people instructions on how to transcribe. The minute that anyone encounters a word that’s unclear to read, or they hit an abbreviation, or a spelling that’s non-standard, they’re going to have questions. We encourage projects to develop transcription conventions that give instruction to volunteers as to what to do when they hit those things.

We actually show it on the transcription screen itself, so it’s right underneath the field volunteers are typing into, so they can find it if they run into problems. (This example is from the Wisconsin Historical Society.)

One of the things we recommend is that you transcribe a couple of example pages and upload those as a separate section, and you can link to them, because people will go try to figure out, “how did they do this?” Especially when they run into things which aren’t covered by your transcription conventions.

As you work through projects, you can iterate. You can improve your transcription conventions and your help text as people ask questions, or as you learn more, or as you discover that they’re doing things you don’t like, you can add pieces of that as you go along. It’s very easy to change.

In fact, we think that, as you’re creating your examples, if you can do that with a handful of staff members, if you can go out into the hall and grab someone and ask them to transcribe a page, and listen to the questions that they ask you; that gives you a great opportunity to update your transcription conventions and your examples.

So in terms of kicking off a project, we mentioned bringing people together and having a mini transcribathon, but these are also great ways to get a project started. Because they are also ways to do outreach.

Now, the Library of Virginia does a transcribathon every month. But you don’t have to do that.

You can launch a transcribathon at the very beginning of a project and bring in people who you think may be leaders within the field or their communities, so you bring people who are active in genealogy organizations or local historical organizations to do an in-person transcribathon. What this does is it allows you to give some hands on instructions and get people over the hump and over the discomfort of “What am I doing here?” “Is this good enough”? And then they’re able to take that enthusiasm and that expertise back to their communities and enlist other people and encourage other people to join in.

They;re also oftentimes a great event that local media likes to highlight for local organizations. So, the New Orleans Jazz Museum did a transcribathon working with French language docuemtns from colonial New Orleans and you can see here on the left a Facebook post from not the New Orleans Jazz Museum, but the Tulane French Department encouraging people to go to this if they are interested in French at Tulane or New Orleans. On the right hand side you can see a post by a participant at a transcribathon at Corpus Christi College Cambridge talking about their experience with someone in person teaching them how to read this medieval handwriting. Which spreads the word even more.

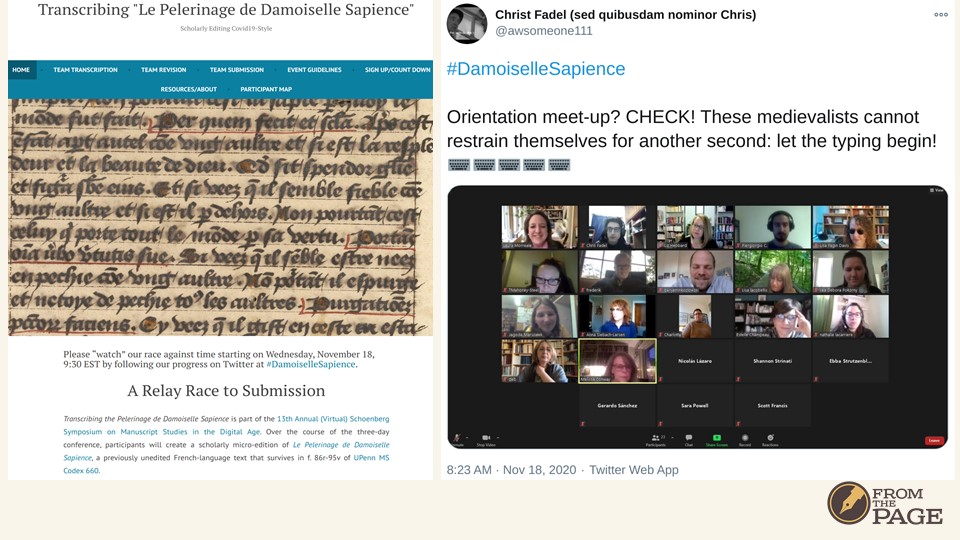

Socially distanced transcribathons are also possible. The communication barrier is higher, but a videoconference kick-off to walk volunteers through the project can work, especially with motivated, tech-savvy volunteers. This example is of a transcribathon for medievalists held in conjunction with the Schoenberg Institute for Manuscript Studies virtual conference.

So, you don’t have to run a transcribathon when you kick off a project… it’s just one way to reach people.

But you should definitely do some outreach and some marketing. So if you have existing outreach venues -- if you have mailing lists, if you have social media accounts, you should definitely use those andmention or push your project. If you have a physical location, you can do handouts. Public libraries often have things at the checkout desk or as your walk out the door that you can grab. You can also look for subject matter enthusiast communities; people who would be interested in the material and might not be local, but who may be interested in your material. On Facebook, you’ll find twitter accounts, there might be magazines we have a whole post that we’ll provide in a follow up email about how to find organizations who might be interested in a particular subject.

We’ve also seen local news channels -- both print and television -- pick up these projects because they are interesting, they’re visual -- you have cool old documents, you have people they can come in and take pictures of. And they are feel-good stories -- they are a way for the local community and retirees to contribute to your mission of preserving memories.

This is coverage by a local TV station of the project from the Seattle Municipal Archives.

Once you kick off a project and you’re starting to get volunteers working on it, you need to figure out how to keep them engaged. It’s not unusual for volunteers to drop by, transcribe a page, and you may never see them again. We have a couple of suggestions for keeping those volunteers engaged. The more you can keep, the more you’ll accomplish.

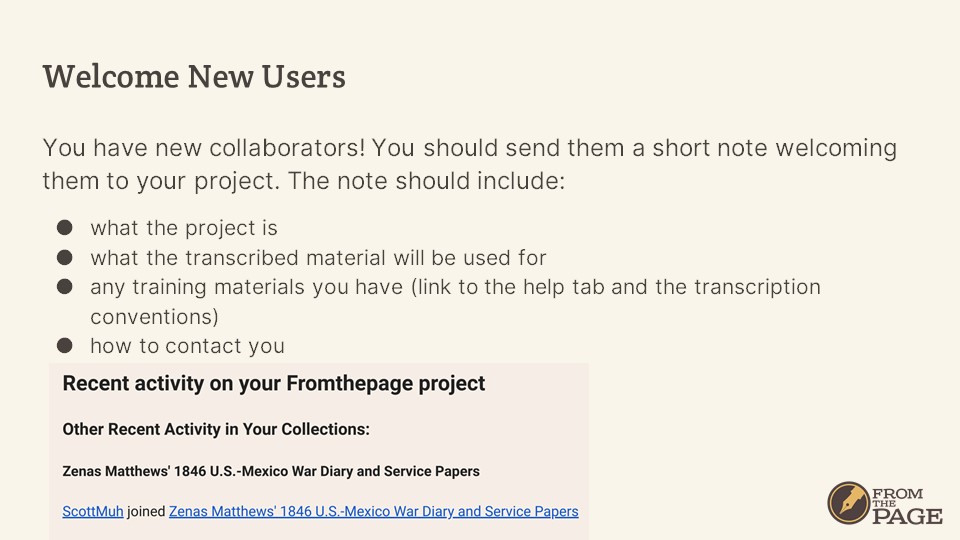

The first suggestion is to welcome new users. We send out a note every night to each project owner telling them what’s gone on in their collections the previous day. You’ll get something like the screenshot at the bottom where it shows you the name of someone who joined your particular project. You can go into your collaborator tab and see people who joined and you can grab their email addresses and you can send them an email -- it can be a stock email -- tell them what the project is, the purpose -- volunteers like purpose -- so what is the transcribed material going to be used for, if you have any training materials, you can link to your help tab and your transcription conventions, and include how to contact you. You want them to be able to ask you questions or share something they’ve found or see if they can bring in a group of 20 people to help you transcribe. All of those things; you want them to be able to find you. So make it easy.

In addition to welcoming new users…

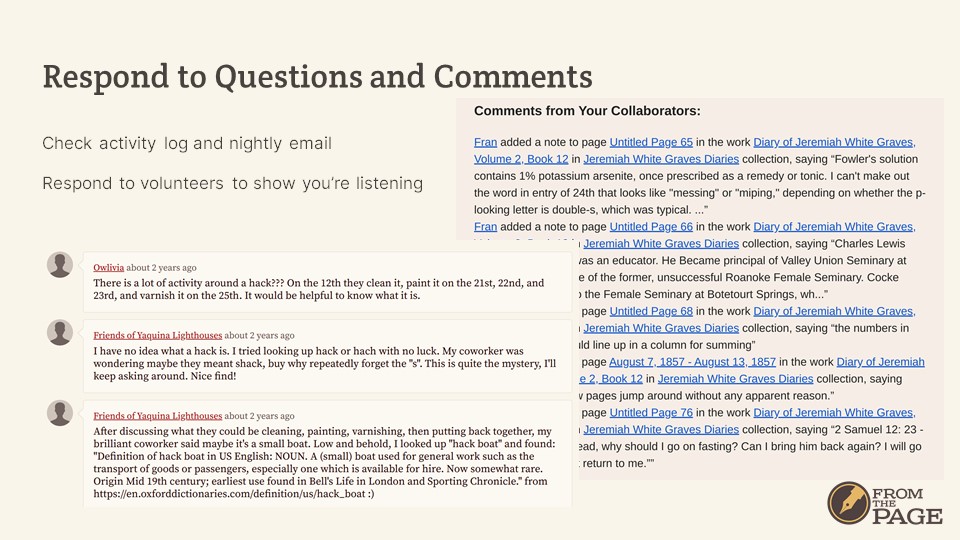

That nightly email will also include comments and questions from your collaborators, from your volunteers who are transcribing for you.

Volunteers can ask questions as they work, and answers by staff or other volunteers will appear in place.

They will get an email that there’s been a response to their comment, because what we don’t want is for a transcriber to comment or ask a question and for no one to respond to them. We want them to feel like they’re being listened to. As the project owner, you’re the one who knows the most about the material and can answer these types of questions.

In addition, each project owner’s nightly email will include any questions or comments, so that you can respond quickly.

The other thing we recommend is that you include your contact information. We have a footer that shows up on every page of your project. This is from the LA County Library, they link to their Facebook, here’s where we are on twitter and instagram, and that “Questions? Contact Us?” is a mailto form where you can email them if you have questions.

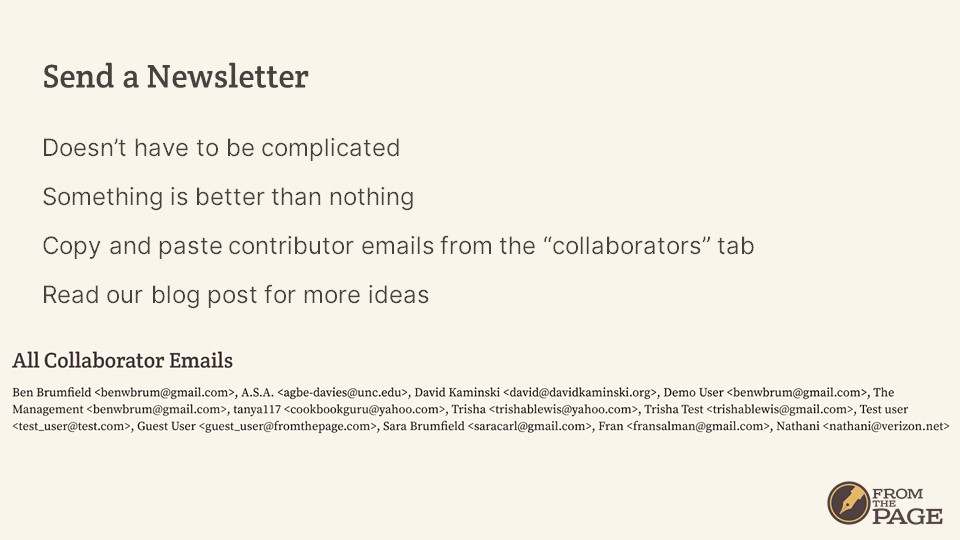

The last thing we recommend is that you send a newsletter. It doesn’t have to be complicated or that big… Doing something as often as you can -- we recommend once a month, but if you can only get it out once a quarter, that’s OK too.

You can pull in a list of all your collaborator emails from the project owner view in FromThePage, and you can just paste them into your email client or if you use something like MailChimp or another newsletter tool you can pull them into there.

We have blog posts that have a lot of examples of what different people will do for crowdsourcing project newsletters.

That’s all the formal presentation we have for you today, but if you’re interested in starting a crowdsourcing project, we have a free trial you can do for up to 200 pages and kick the tires, figure out how FromThePage works and what you can do with it.