This post is transcript of my presentation at the 2018 meeting of the American Historical Association, on the panel Primary Sources and the Historical Profession in the Age of Text Search, Part 3: Digital Texts and the Future of Digital History: Challenges, Opportunities, and Experimentation in Digital Documentary Editing, including slides and audio.

Good morning. Let me start by saying that I am not a historian--my background is in software development--but I wanted to communicate some of my observations from working with digital edition projects.

Let's go back to a specific moment in time. On March 15, 2017, the Washington Post broke the story that the adminstration's proposed budget for the NEA and the NEH was $0.

This launched a conversation online--among many of the people in this room, I'm sure--asking: What does this mean? What does this mean for us? What does this mean for my institution? What does this mean for my discipline?

There were similar conversations happening among the technical staff who work on digital history projects.

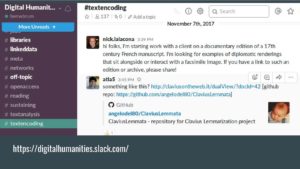

This is the Digital Humanities Slack workspace, and this is the text encoding channel. (I'd recommend anybody who's interested in discussing [digital editions] to join it.)

Normally, you have conversations like this: [pointing] Here's somebody saying, "What's a good way to present diplomatic transcriptions next to a facsimile image?" Other people respond, saying, "Here's a good example, check this out."

So there are lots of technical conversations on the text encoding channel on Slack. But roughly March 16th or 17th, the conversation revolved around one question:

What happens to our editions if we are all fired? If we lose our jobs, these things that we've been working on so hard, that we've been pouring our hearts into -- are they still going to be around? What's going to happen?

It turns out that this is not a new question. People have been asking questions about preservation of digital projects for years, and they've been a part of the debate about digital editions versus print editions for at least a couple of decades, I'd imagine.

Let me give you some quotations from Elena Pierazzo's Digital Scholarly Editions, [print, preprint] where she's talking about this distinction: "Printed scholarly editions have long shelf lives." And that phrase "shelf life" is important, because a printed edition sits on a shelf. And that is its sustainability proposition -- the shelf in the library.

Digital editions change, and they change not just because of technical obsolescence, but because of changes in researcher demands, changes in [technical] platforms, changes in capabilities. As we discover that we're able to do new things, we want to do them.

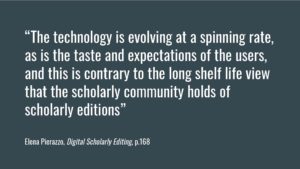

That means that the technology evolves rapidly. It's really hard to keep up. And this is a conflict with the view that the community holds of scholarly editions, where Andrew [Torget] can talk about an edition from nearly a hundred years ago which is still incredibly valuable to the historical community.

How can we make digital scholarly editions as sustainable, as preservable as print editions?

I'm going to say, first off, that there's a caveat: print editions are not necessarily that sustainable. They're not necessarily that cheap. Just because I [as an editor] am not paying for the shelf space and the cataloging effort and the conservation of a print edition--that's externalized to a library--doesn't mean that someone's not paying for it. And eventually as library technology changes and more materials are moved off-site, the number of editions that are being preserved in print by library staff are reduced.

The other thing is, that in addition to not necessarily being that cheap, [print is] not necessarily that permanent.

This is a picture of the Public Records Office of Ireland in 1922, when it was on fire during the middle of the Battle of Dublin. This destroyed a huge swath of historical information. We see similar things elsewhere -- we heard Marek [Slon] talking yesterday about the Polish records that were destroyed in the Warsaw Uprising. But it doesn't even take wars to do this; anyone who's tried to work with the 1890 Census knows the story there.

Print is not perfect, but it is cheaper and better to preserve. So what can we do for the digital to make it cheaper and better to preserve, knowing that we won't achieve perfection, and we might not even achieve the standard that print has attained.

I'd like to propose three principles--three suggestions--for making digital editions more preservable. Joe [Wicentowski] has already talked about two really important things: using standards and using open source technology, which are both important for preservation.

The first [principle] I'm going to talk about is exposing your data.

We see over here the Foreign Relations of the United States. On the left-hand side, we see the site, which Joe showed us. We also see the data[on the right-hand side] -- we see what backs the site.

There are many ways to expose your data, and there are many reasons to separate the interface from the data, but one of the reasons is that it's a lot easier to preserve a file--even a file that's heavily encoded like this one--than it is to preserve a working, functioning website.

If you expose your data, you have [options] for hosting it for preservation and publication. One is your institutional repository -- get your data out, and put it in a repository. Usually repositories are happier [accepting data after it's published]; the same might be true of TAPAS. But there are also some non-traditional hosts I'd like to suggest.

The Internet Archive is a great place to park facsimile images. One of the great things about it is that you can embed those facsimiles within your own editions for no cost. So that's an exciting option for reuse and preservation at the same time.

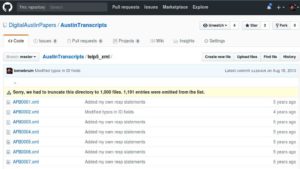

The other option--which Joe talked about--is Github. This is the Digital Austin Papers, and the TEI-P5 transcripts that Andrew was talking about. We wanted to put these all online in part because of the publication process that Joe was talking about, but also because we wanted to allow scholars to get at the data in some way that wasn't the interface.

Reusability is really important, and exposing your raw data enables other scholars to do new things with your data, yes, but also to recreate your digital edition using your editorial work. And some of those scholars might be you, twenty years from now, after your interface dies.

The Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition has done this, and here's a good example of the things you can do with [a Github repository for TEI]: You can see the changes of a hand edit, done twenty hours ago. You can see the hand mark-up very easily online, so it's useful [in edition creation] as well.

My second suggestion is to minimize the technical complexity of your publication.

People have been talking about this recently in the Global Outlook:DH group, trying to provide digital humanities tools to people in the Global South that don't have the technical infrastructure that we do. They've launched the Minimal Computing project to serve those activities.

One Digital Humanities activity is digital scholarly editions, so one thing that came out of [Minimal Computing] is Ed, a [platform for] minimal editions. The idea behind a "minimal edition" is that you have people doing TEI encoding, but all of the hosting and publication is done in a static site published on Github for free.

And you get editions that are indexed and are readable.

But this isn't necessarily a new idea. This is the same thing that TEI and XSL editions were doing fifteen years ago as well. Static sites are really very useful, and they're very easily preservable.

But they're static. How can we preserve interactive content the same way?

Sometimes you can do this. One of the things we worked on on the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition was the ability to visualize the networks of people who are mentioned within the corpus. This kind of visualization, this ability to click around on nodes of people and see documents, is actually something that can be preserved. You have this graph--[a visualization tool] which is asking for data from some system, usually via an API. There's no reason that that data couldn't be made static. There's no reason that those communications couldn't be turned into preservable static data.

That doesn't mean you can do every interactive feature of a digital edition in a static site. The Digital Austin Papers [analytical search result page] is a great example: any time that users are typing in words for a full-text search, [the results cannot be made static]. Unless you're willing tell users to go use Google to search your edition, there are limits to the static site approach.

My final suggestion is to consider format shifting. This is [a strategy] that comes from the archivists who are working on video game preservation, and are dealing with game consoles from the early '90s that use monitors and display formats that nobody uses any more, and maybe hasn't since '85. They say, the best way to preserve this experience is to take a video.

So if you have an interactive display--if you have graphs that you're making as part of an argument within your documentary edition, showing interesting things that have been found within the edition, why not make a video of them. [You can] capture them as a screencast. Here's an example of software history visualization that was done that way and put on YouTube. We understand how to archive video in ways that we don't understand how to archive the interactive experience.

Finally--bringing us back to the original comparison--another really important format shift for purely textual material is to print it out.

Brumfield Labs provides software development expertise for digital humanities projects, focusing especially on digital scholarly editions, crowdsourced manuscript transcription, and IIIF. If you'd like to talk to us about a project, email us at benwbrum@gmail.com.