Last May, Ben and Sara Brumfield hosted a webinar on successful crowdsourced indexing. The presentation, linked below in a video and embedded as slides, presents a walkthrough of how project staff selected material, recruited volunteers, developed instructions, encouraged engagement, and used volunteer contributions to improve public access. You can sign up for future webinars here.

Read through Ben and Sara's presentation:

This is Sara Brumfield with FromThePage. I’m here today with Ben, my partner, and we wanted to tell y’all what we’ve learned over a decade of running crowdsourcing projects, and how that applies specifically to indexing projects.

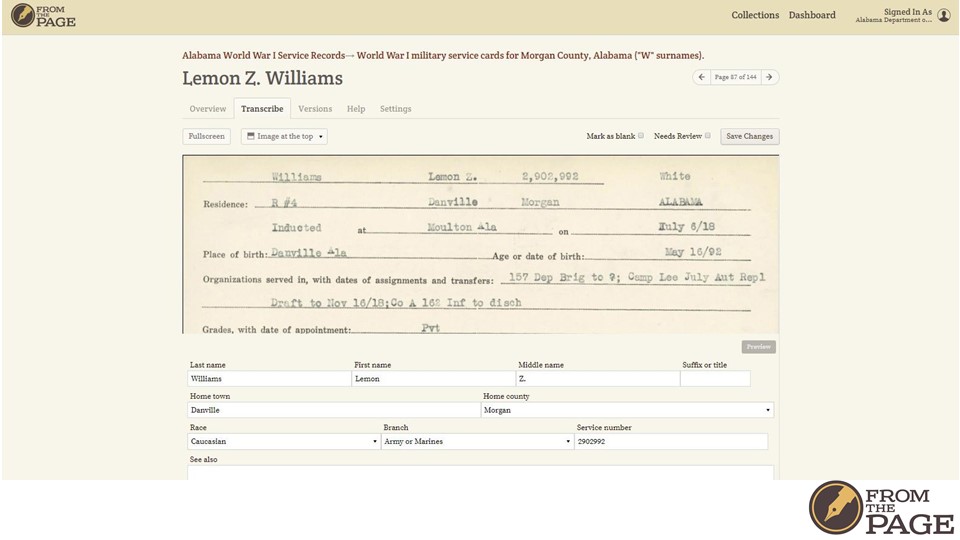

Let’s start by defining indexing. In our software FromThePage, Indexing is asking users to transcribe specific elements of a digitized document into structured data fields.

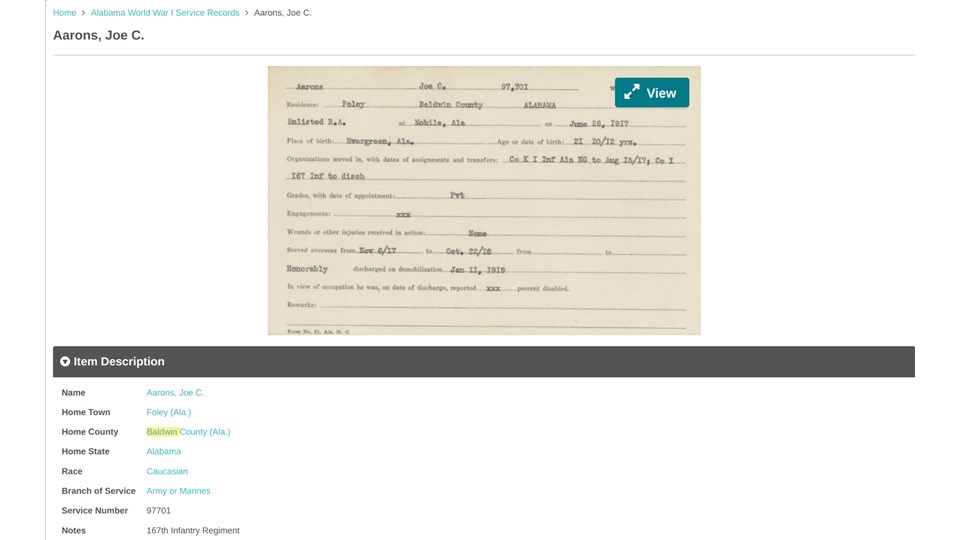

This is an Alabama World War I service card, and you can see that volunteers are asked to separate out different portions of the name in the form, and aren’t asked to enter the soldier’s serial number, rank or transfer history.

The project owner has configured the specific fields to be indexed, and the format to display them in.

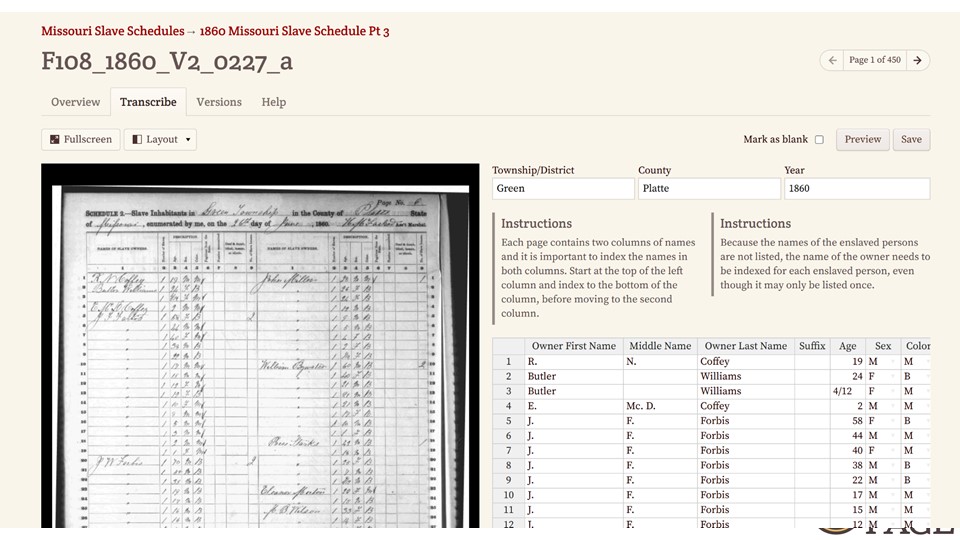

Indexing may also include spreadsheet-style projects.

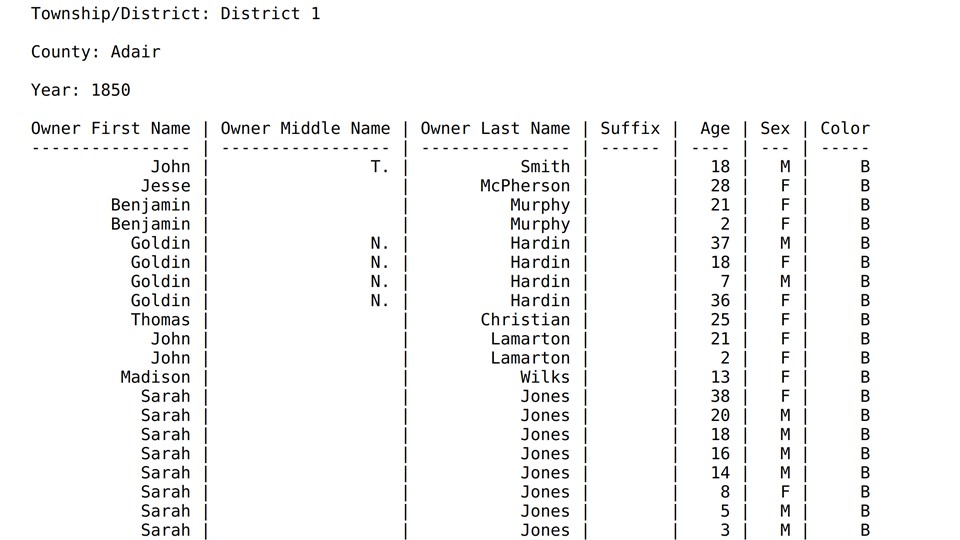

Here is a project indexing the slave schedule to the 1860 United States Census, in which different structured data is being indexed. This includes page-level fields for the header on the census form, but also has a spreadsheet to create multiple records per page.

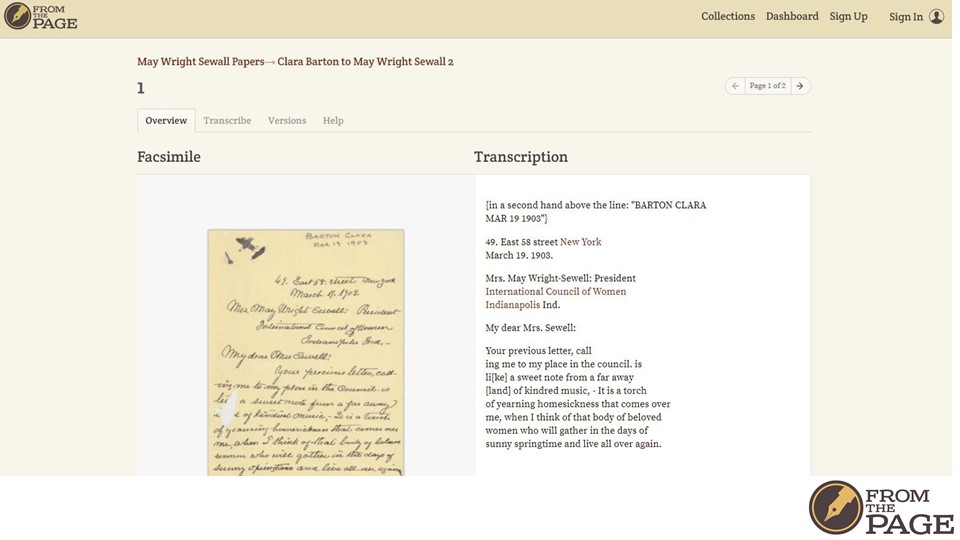

These indexing projects differ from full-text transcription, like this example in which every word of the letter has been transcribed by volunteers.

Our indexing features were developed by and for state and national archives. Funding and guidance came from the Council of State Archives in the US.

We’re going to talk a lot about projects from the Alabama Department of Archives and History and the Missouri State Archives, so we wanted introduce the cast of characters; here’s the people who run the 2 projects we’ll talk most about. On the left is Meredith McDonough, an archivist and digital assets coordinator at Alabama; then we have Steve Murray, the state archivist of Alabama. On the right is Christina Miller, the reference services manager at Missouri State Archives, and John Dougan, the state archivist of Missouri. Now you have some faces to put with the names.

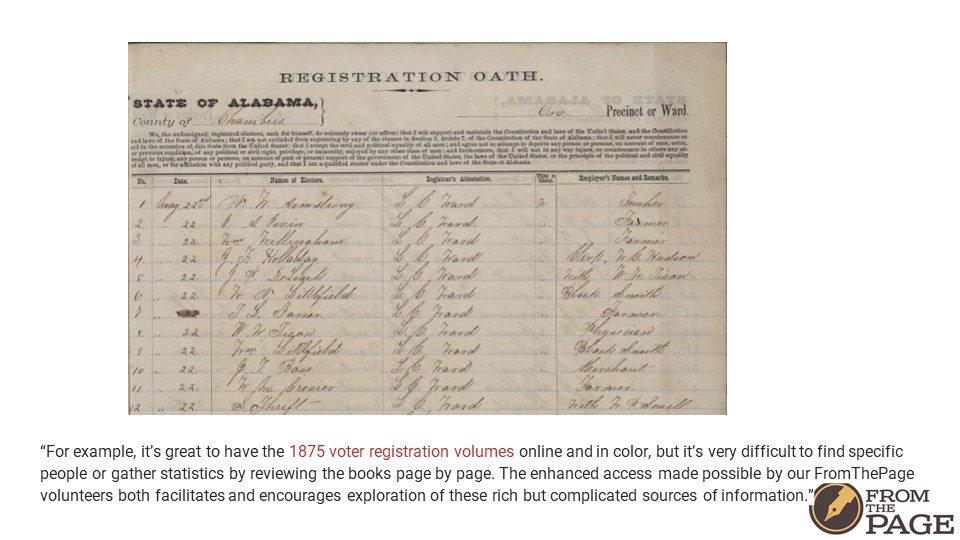

Let’s talk for a minute about what kind of material should be indexed.

Access is hard

Users need page-level indices

Lots of named individuals

Indices to other documents

Meredith knows that just like they’ll never scan all of ADAH’s physical records, they will never transcribe all of their digitized records. Instead, they’re focusing on collections that would most benefit from extensive transcription, like this.

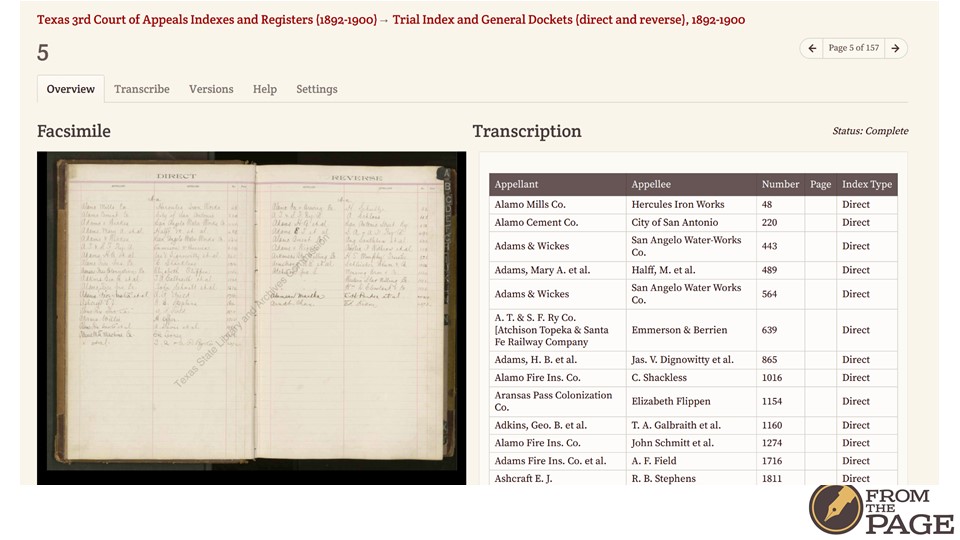

This is an index from the Texas State Library and Archives commission; they’re transcribing an index to court cases. Those court cases are hard to find unless you page through the digital images of the original index; indexing this will increase the likelihood of the court case records being used.

Now let’s talk about writing instructions for your volunteers

We support three different types of help in FromThePage.

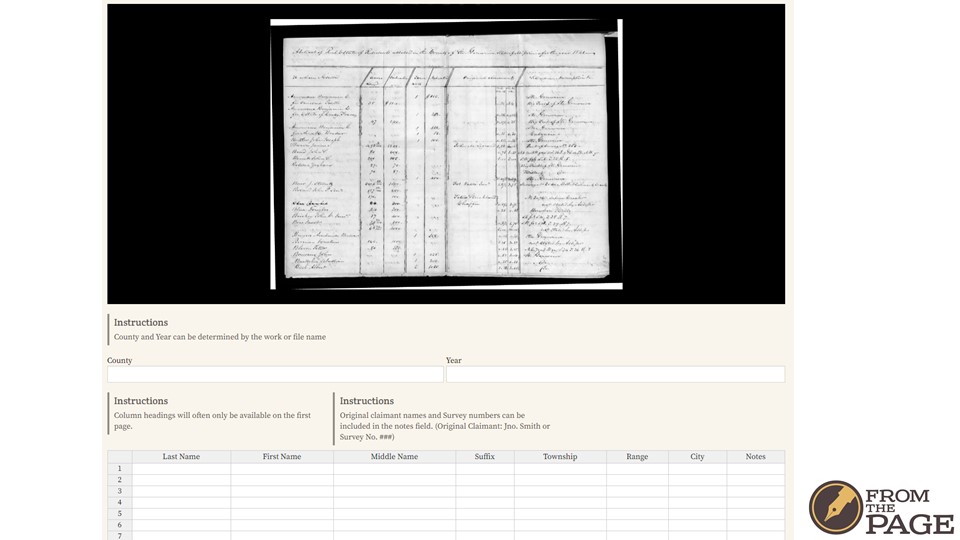

This is a county tax list from 1841 from the Missouri State Archives. They’ve added these “instruction” blocks, that we highlight by a vertical bar, to help their transcribers.

The cool thing about this is that the volunteers are likely to read them, since they’re right next to the fields where they’re doing the work.

They also give volunteers a place to put random stuff they find; the notes that can be associated with a section

You’ll also notice that they’re not collecting every single field that’s on the original.

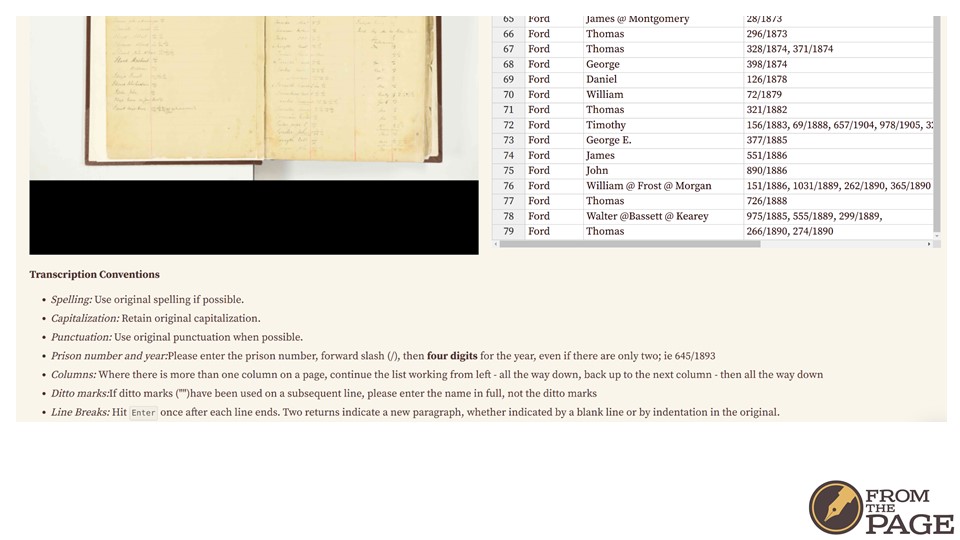

Here’s an example of transcription conventions from the Queensland State Archives’ Index to male prisoners admitted - HM Prison, Brisbane (Boggo Road) 1870-1928.

The third type of help that we have in FtP is what we call the help tab. I’ve got a couple of different examples for this from different projects.

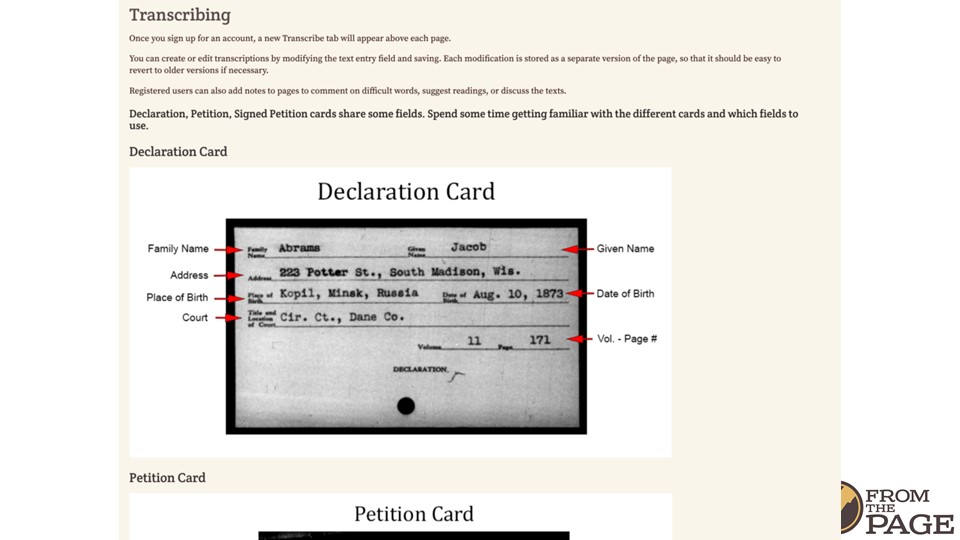

This is an example from the Wisconsin Historical Society. We love how they annotated an image to point to different fields and included it in their help tab.

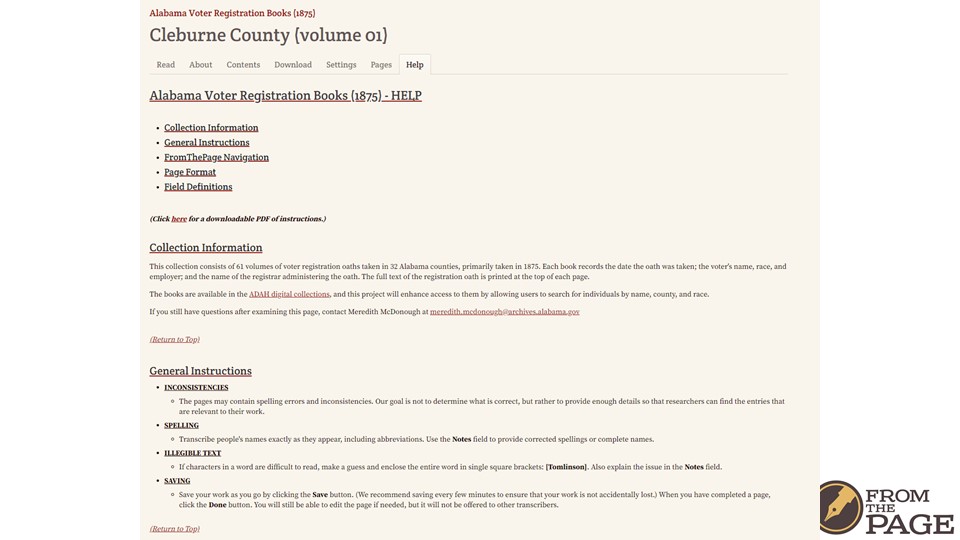

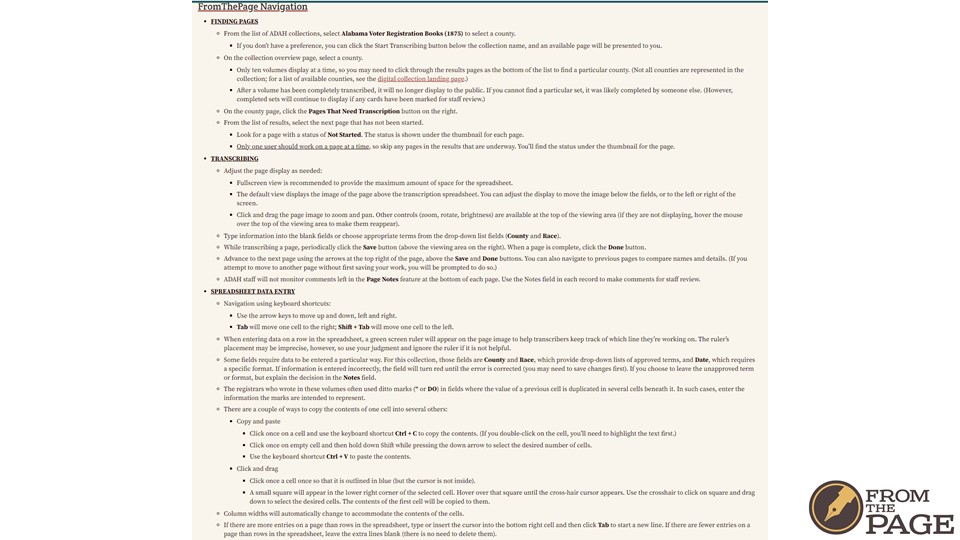

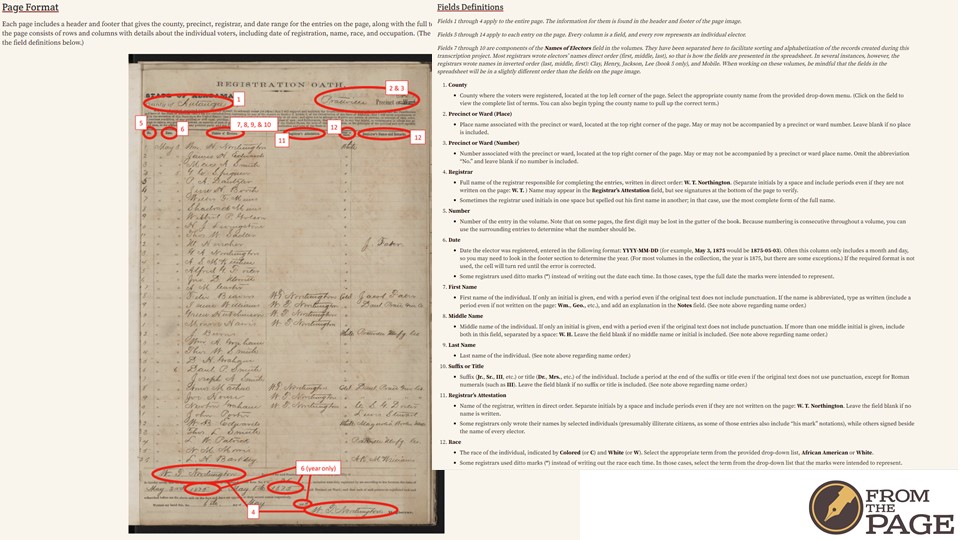

The next four slides are all taken from the help tab of Alabama’s voter registration books project.

It’s really extensive. Meredith created text that gave people a guide to the collection, some general instructions for handling common issues like irregular spellings or illegible text.

Hints on navigating the project within the FromThePage software.

They also included an annotated scan with an explanation of each field they’re collecting.

This is kind of intimidating, but Alabama has been running projects for four years. They’ve been able to build on previous projects -- and you can build on some of their practices, too!

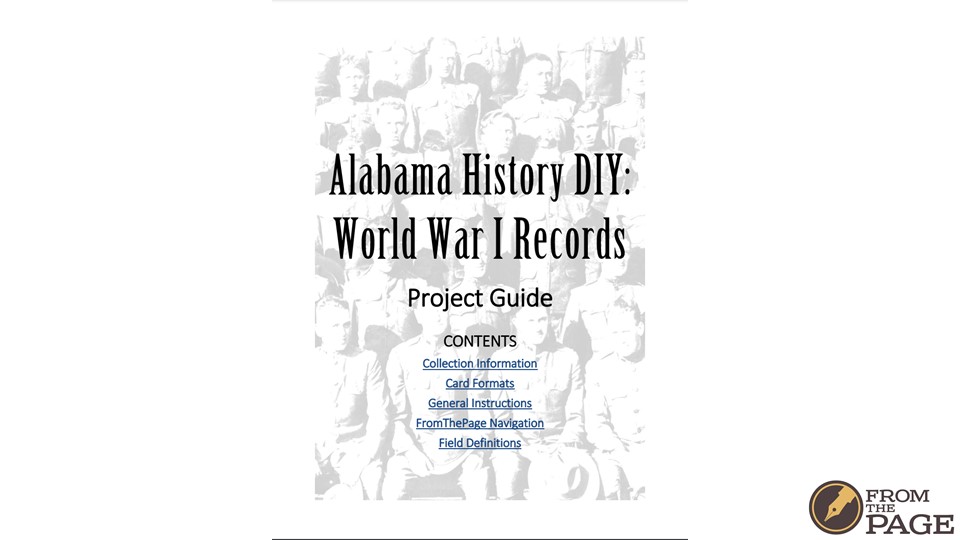

People like having something they can print out and have next to them. Alabama links from their help page to their PDF project guide. This is actually the same material that’s in the “help” tab, reformatted for PDF.

After you’ve uploaded material and defined instructions, you might want to do a soft launch.

In fact I would argue that you can be doing this as you write your instructions, because the things you learn from the launch process will help you improve your documentation and project.

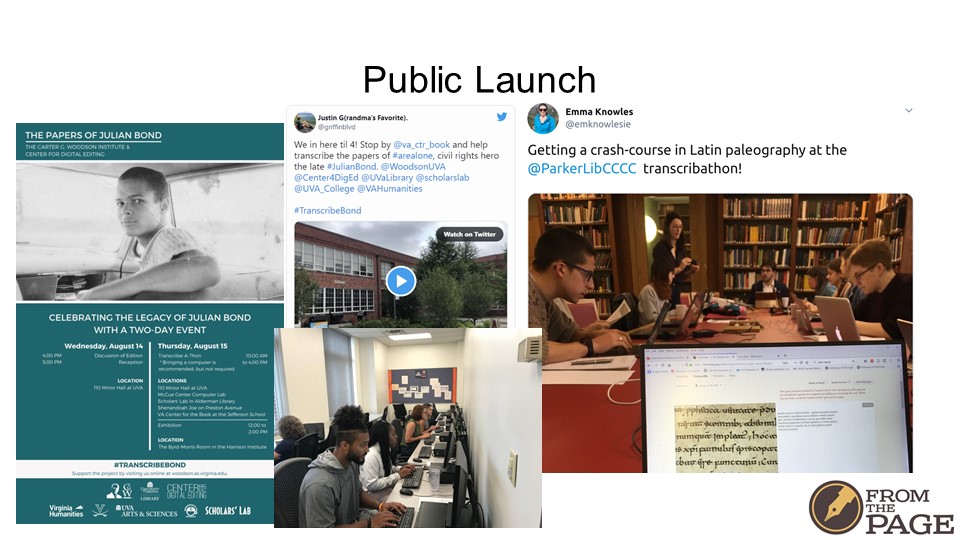

Once you’ve given the project a shake-down cruise, it’s time for a public launch. You can hold an event at the very beginning of a project and bring in people who are active in genealogy organizations, local historical organizations, or descendant communities.

What this does is it allows you to introduce the material and project goals. You can give hands-on instructions to get people over the discomfort of “What am I doing here?” “Is my work good enough”? And then they’re able to take that enthusiasm and that expertise back to their communities and enlist other people and encourage other people to join in.

In addition to giving volunteers hands-on training, these events are also great publicity. You can see the Julian Bond Transcribathon promoting its hashtag in a poster, with volunteers promoting the project on social media. You can also see a post by a participant at a transcribathon at Cambridge talking about their excitement learning how to read medieval handwriting. Which spreads the word even more.

The Missouri State Archives does a fascinating exercise at their launch events. After they’ve explained the format of the material and given people instructions on how to index each field, John, the State Archivist, starts to index a page. And he’s terrible at it! They have the participants yell out what he’s doing wrong, and what he should be typing instead. It makes the volunteers more confident in their own skills–after all, they just corrected the State Archivist–and reinforces the right way to handle common errors.

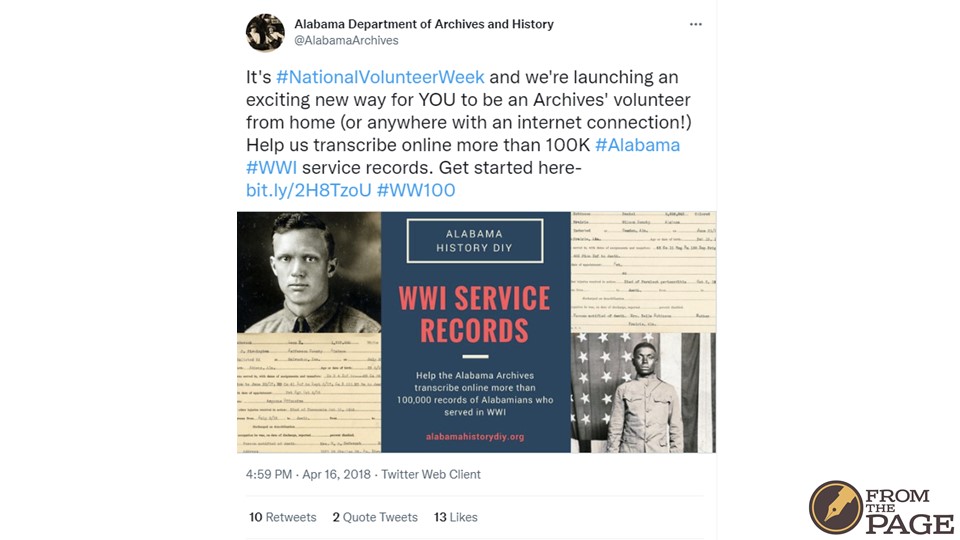

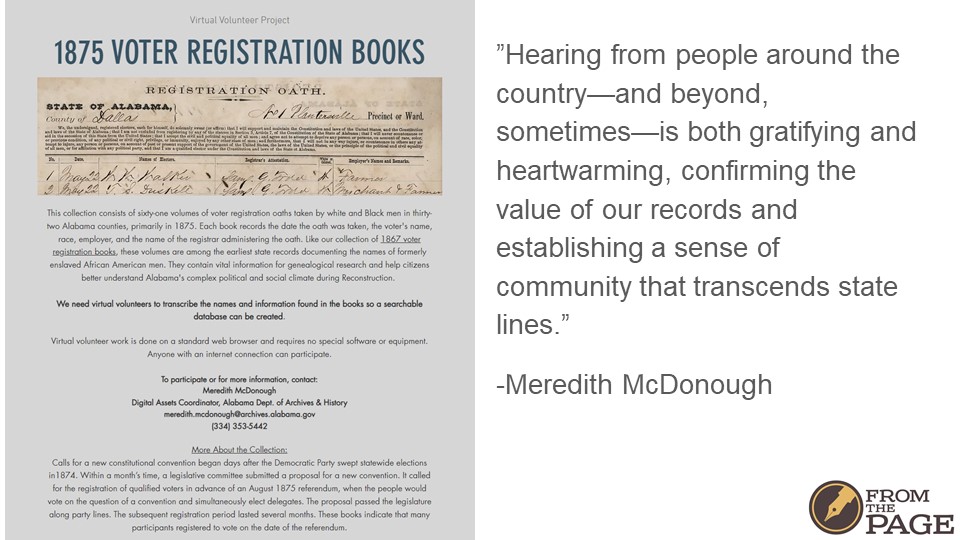

Promoting the project through social media can be ongoing. Meredith says, “we have been stunned by the number who learn about our projects through virtual word-of-mouth: Tweets, Retweets, shares, and likes.

Alabama keeps their large FromThePage projects private and then adds collaborators to the projects as they express interest, establishing a direct line of communication. Meredith says that these emails often begin with “I just saw a post about your project on . . .” or “I’m not from Alabama, but . . ."

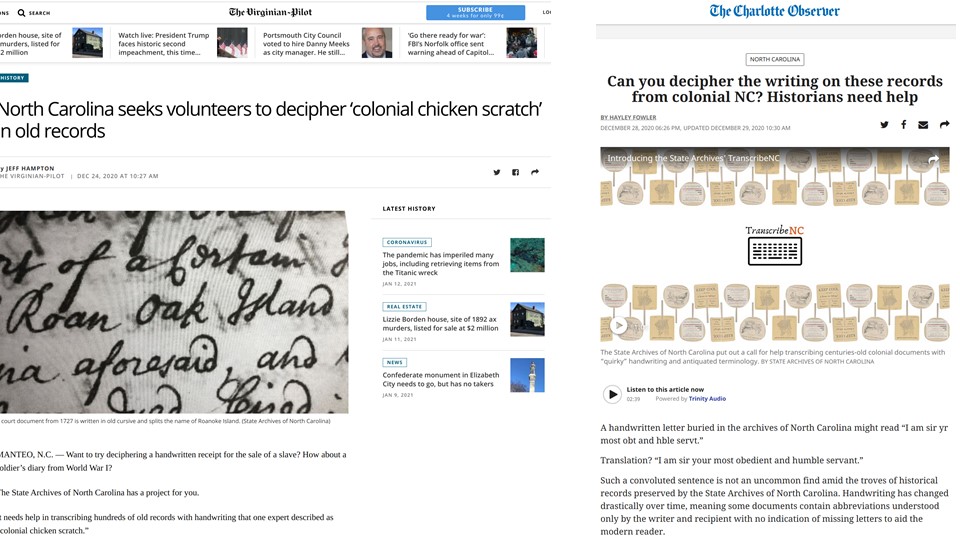

We’ve also seen local news channels -- both print and television -- pick up these projects because they are interesting, they’re visual -- you have cool old documents, you have people they can come in and take pictures of. And they are feel-good stories -- they are a way for the local community and retirees to contribute to your mission of preserving memories.

This is coverage by a local TV station of a project from the Seattle Municipal Archives.

Traditional print media coverage is also important. The two busiest days on our software platform were over the Christmas holidays, when two newspapers published articles about a project at the North Carolina State Archives. People together with their families and looking for something meaningful to do together – or perhaps looking for a productive escape.

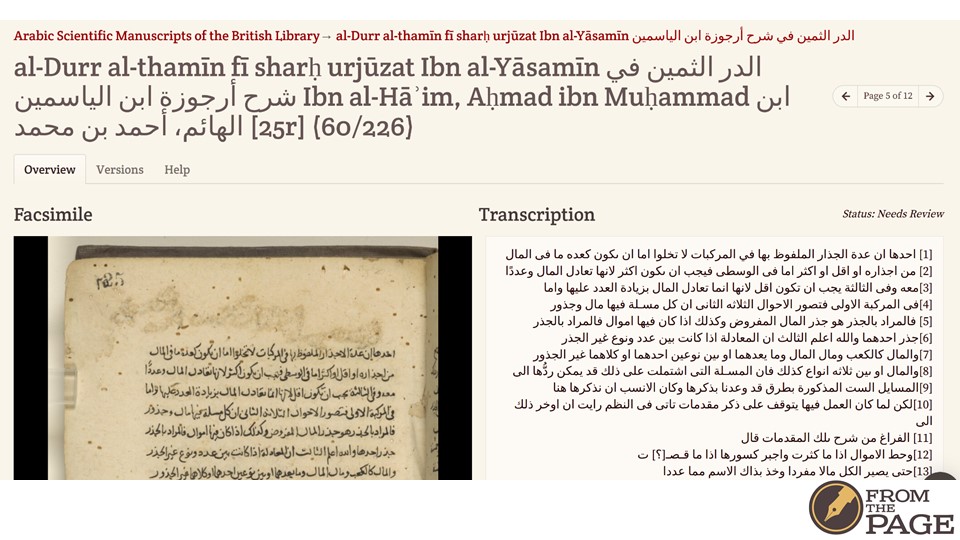

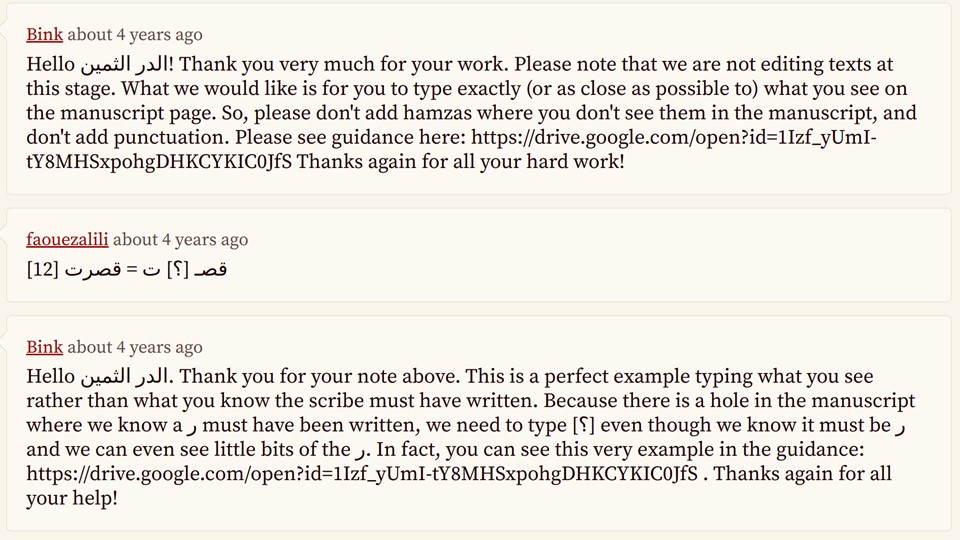

One challenge for volunteer projects is to gently provide correction and guidance to users who are not following the instructions, or are enthusiastically following the wrong instructions. And volunteers want to do good work! But sometimes a skilled, enthusiastic volunteer from one project starts working on a different project that follows different conventions, but they are used to the way the old project did things. Sometimes this also happens when the project has given guidance at the beginning, but not to new volunteers.

That happened when the British Library transcribed its Arabic scientific manuscripts; they held a launch event in London that was well attended, and seeded the project with volunteers that understood the instructions well. Late in the project, a new volunteer discovered it and started “correcting” the medieval text to modernize the spelling, contrary to the goals of the project.

The project staff were able to intervene by leaving notes on the pages the user had edited, and gave some gentle guidance and encouragement to the user.

Often, however, individual correction can drive volunteers away, no matter how tactfully done.

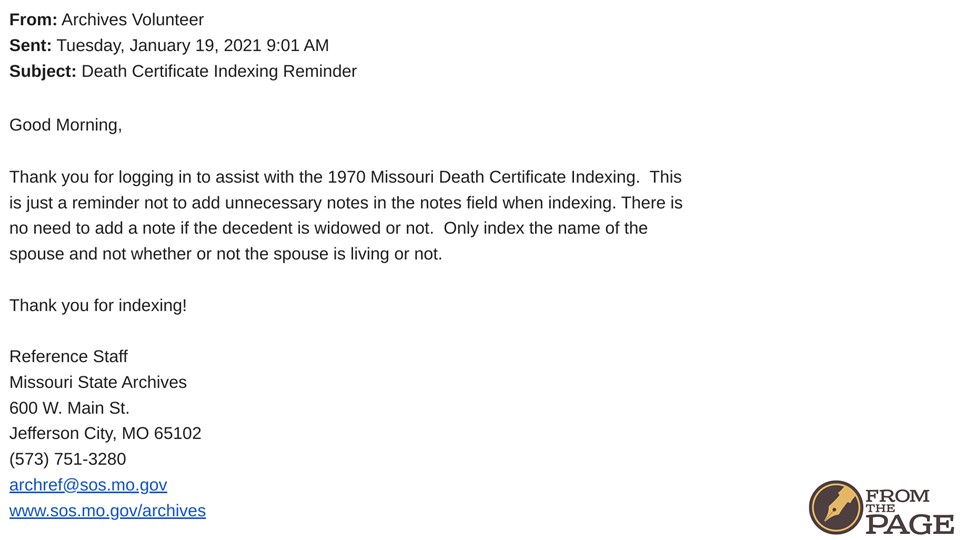

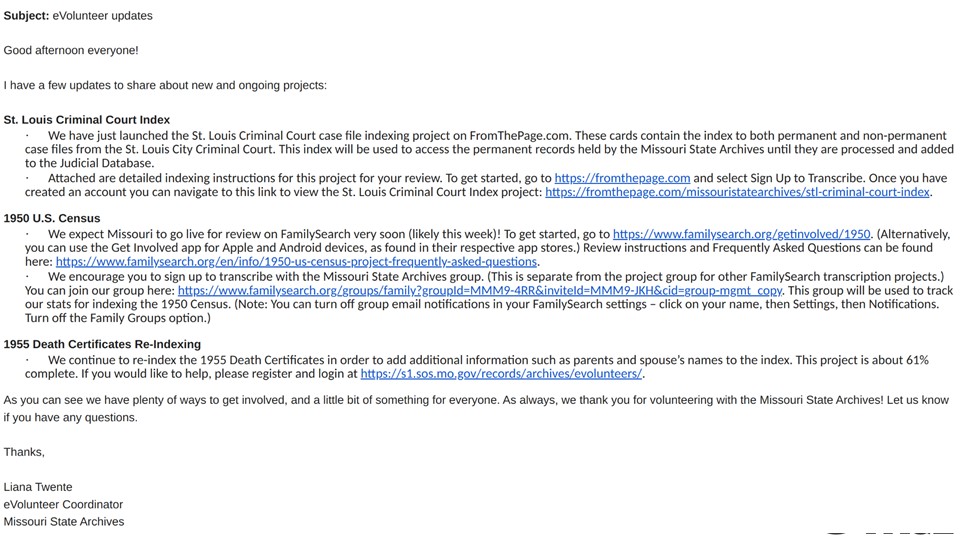

The Missouri State Archives addresses this problem by sending email to volunteers that look like regular updates to the whole volunteer pool, highlighting the issue they’re seeing and reminding the volunteers of their expectations. However, the email only is sent to the errant user; correcting them without singling them out.

Let’s talk about what happens after the projects are done. There are two things to think about here: what happens to the volunteer community, and what happens to the data?

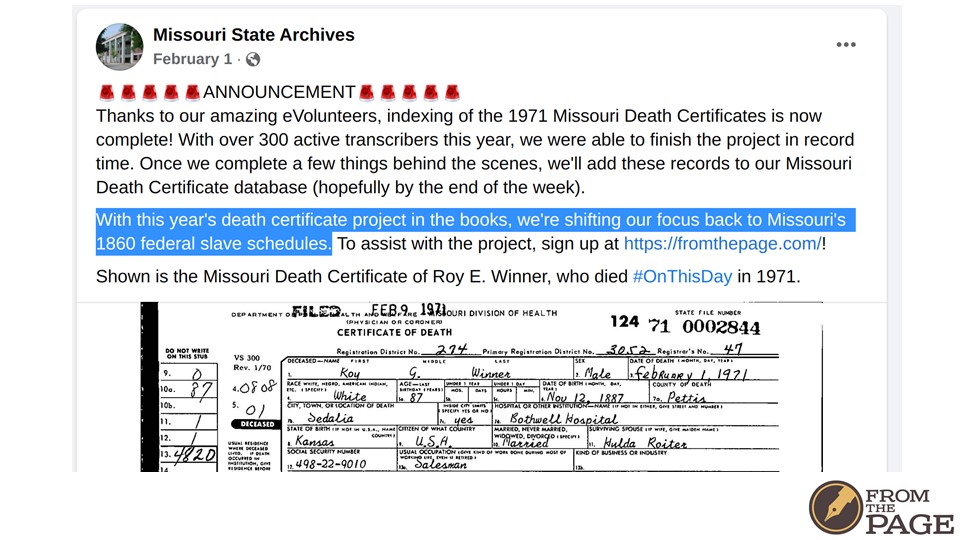

Just like we have a responsibility not to waste volunteers’ labor, we feel like successful projects recognize that volunteers make social connections through their work and have formed a real community. When a project ends, volunteers can be saddened to lose the experience. One option is to point them to other projects at your institution, as you see in this social media post.

However, you might not have a project ready, or the projects you do have may not match volunteers’ skills and interest. Another option is to point volunteers to similar projects at other institutions, while reassuring them that you’ll let them know about new projects at your own institution when they are available.

This email goes out to current volunteers for Missouri’s projects, but also former volunteers who might have moved on to other institutions' projects and would be interested in returning to Missouri when a new project goes online.

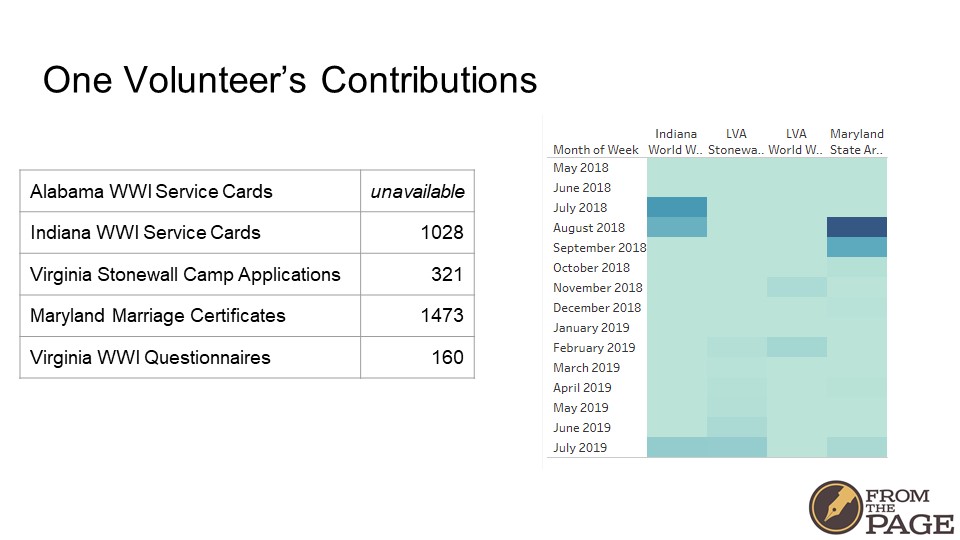

And we do see people moving from one project to another.

This is a graph of one volunteer’s contributions to four projects at three other state archives after the Alabama project was finished.

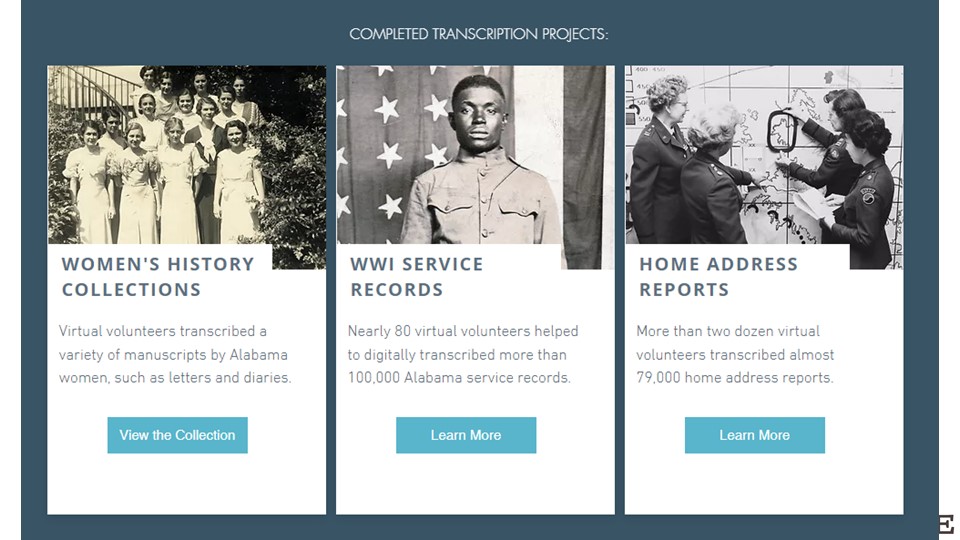

It’s important to acknowledge your volunteers in some way at the end of the project.

I really like how Meredith gives a count of volunteers records for these projects.

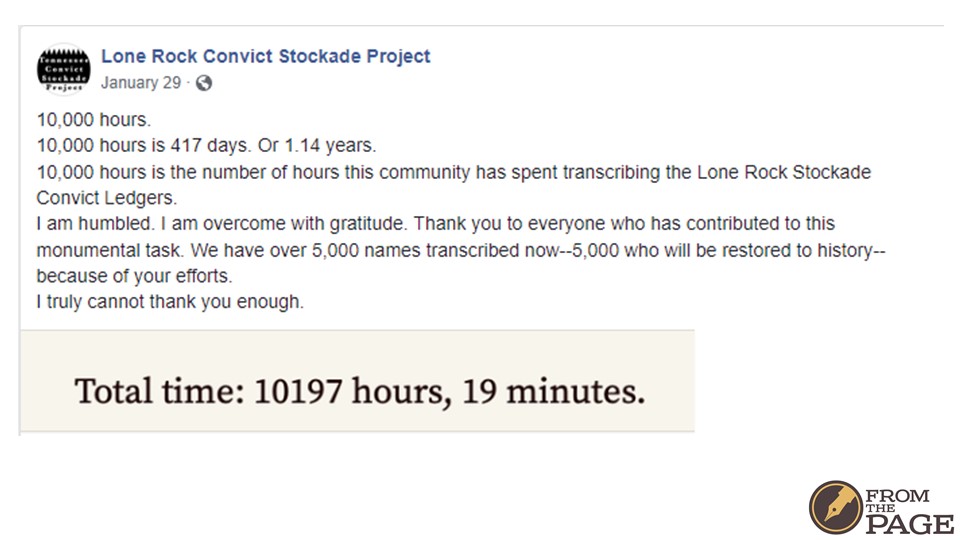

This is an amazing social media post by the historian running the Lone Rock Stockade Convict Ledgers project.

The other part of finishing a project is extracting data.

FromThePage supports several export formats; some indexing projects use more than one.

It’s important to figure out where your exported data will go.

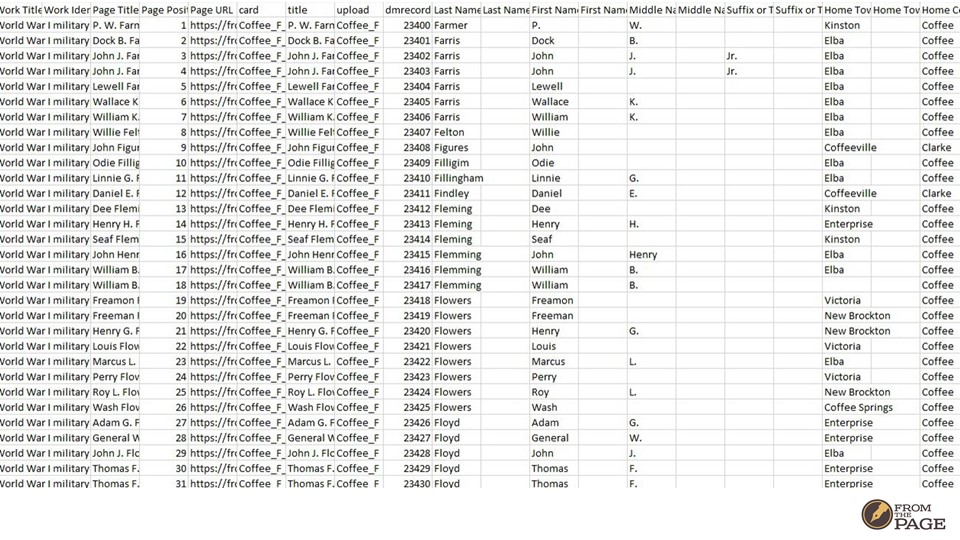

This is a spreadsheet export of the Alabama WWI service card project. Meredith pulled this out, and then she used this material to….

Turn her digital “stacks” of cards, with just top-level metadata for 400-plus cards, into individual cards indexed by name, location, and 4 other fields. You all know what this means to users, and how much time it saves, and how it makes finding the record you’re looking for possible.

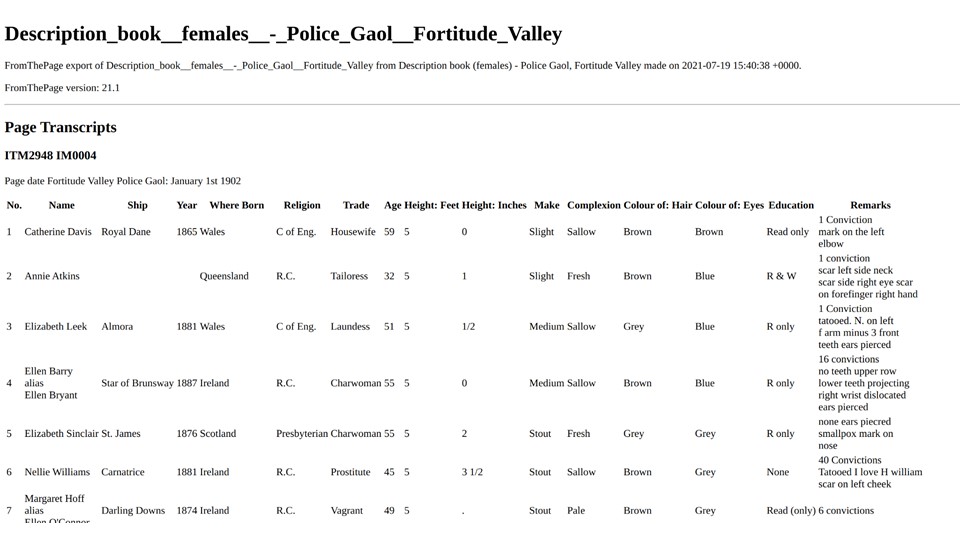

This is a similar spreadsheet export of the Description Book from Police Gaol, Fortitude Valley from Queensland State Archives; this project was a spreadsheet transcription project, but the data that is exported is very similar. This is a great starting point for analytical research work; in fact the Library of Virginia uploads their datasets into the Virginia Open Data Portal for academic researchers to use.

HTML Export is less useful for indexing projects, but updating digital library systems with human-readable transcripts can still be valuable.

What if you don’t have a place to put spreadsheet exports from ledger-style data, or are working with a system that has a single, plaintext transcript field? This is our page level text export; it’s human readable, searchable, but it’s also future-proof because it’s a machine readable format called markdown.

We want to leave you with this quote from Meredith about their perspective, and open up the call for discussion.