Last month, Ben and Sara Brumfield hosted a webinar on teaching with primary sources using FromThePage. The presentation, linked below in a video and embedded as slides, presents a walkthrough of how scholars can use FromThePage in the classroom. You can sign up for future webinars here.

Watch the recording of the presentation below:

Read through Ben and Sara's presentation:

This is a combination of show & tell and project ideas. Hopefully you’ll come away inspired!

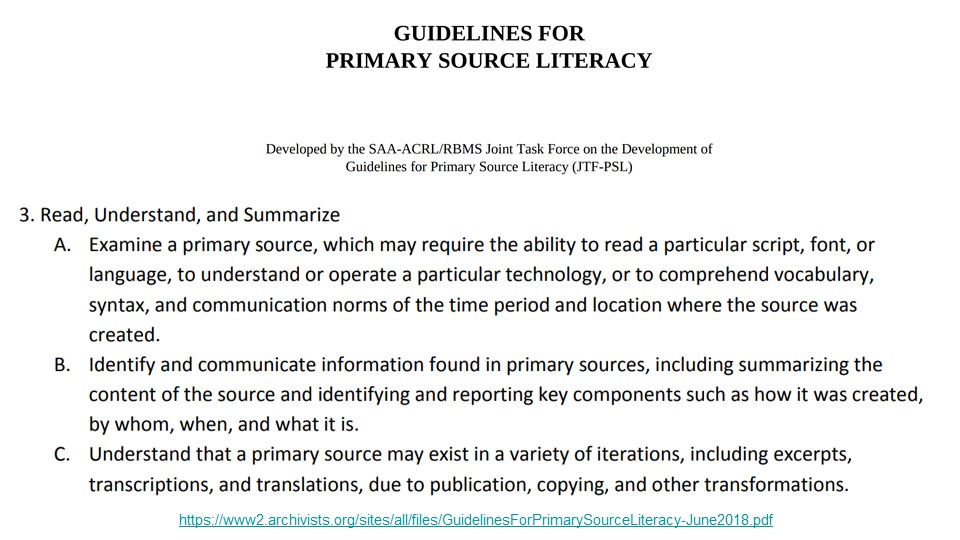

FromThePage is most popularly used for transcription, and transcribing primary source documents in FromThePage falls squarely within guideline 3 of the SAA/RBMS’s guidelines for primary source literacy. As we’ll hopefully show, though, FromThePage can also be used in conjunction with finding items in the archives and with higher level skills like summarizing and describing documents.

We like telling stories, so we thought the best way to get your creative juices flowing was to show you a bunch of different examples.

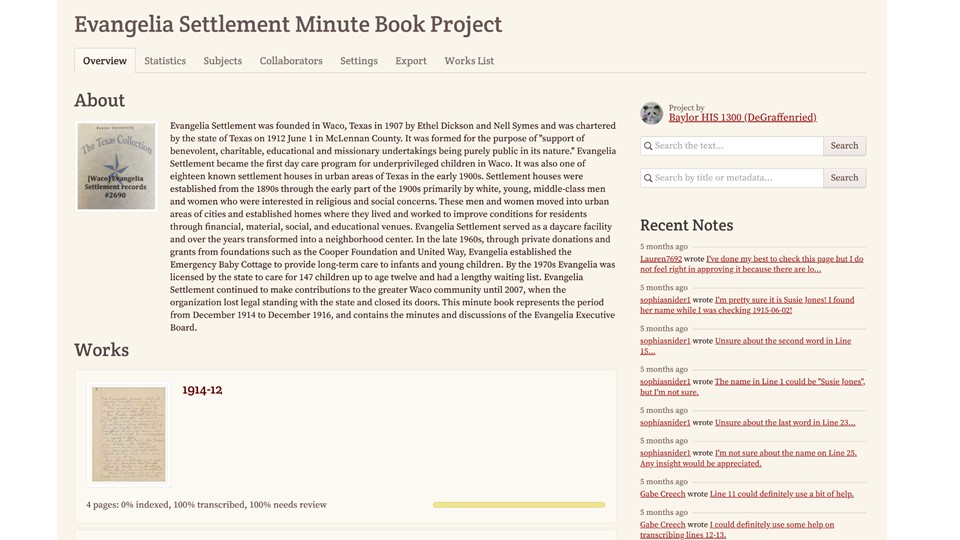

Julie deGraffenried is a history professor at Baylor teaching first-year history majors about early childhood education during the Progressive Era. She was familiar with crowdsourced transcription, and wanted to find something that would capture local interest.

So she approached Benna Vaughan, archivist at the Texas Collection.

Together they were able to identify the minute books of the board of Evangelia Settlement House as appropriate. Evangelia Settlement provided the first childcare services for working class citizens of Waco, and the 1914-16 minutes of its board are excellent primary sources covering childcare discussions within the Progressive movement.

They designed the course that would satisfy the university’s new civic engagement requirement through transcribing primary sources.

The students transcribed the document and edited each other's transcriptions.

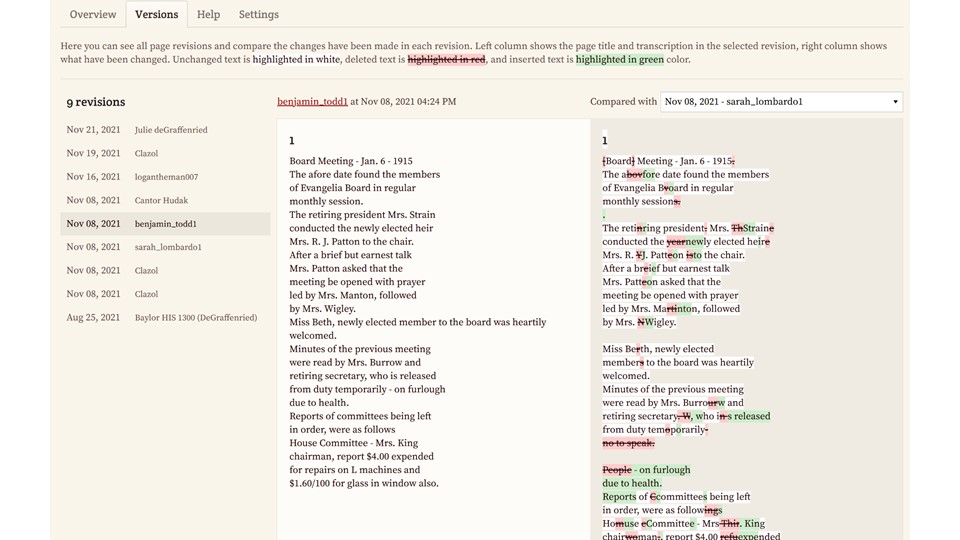

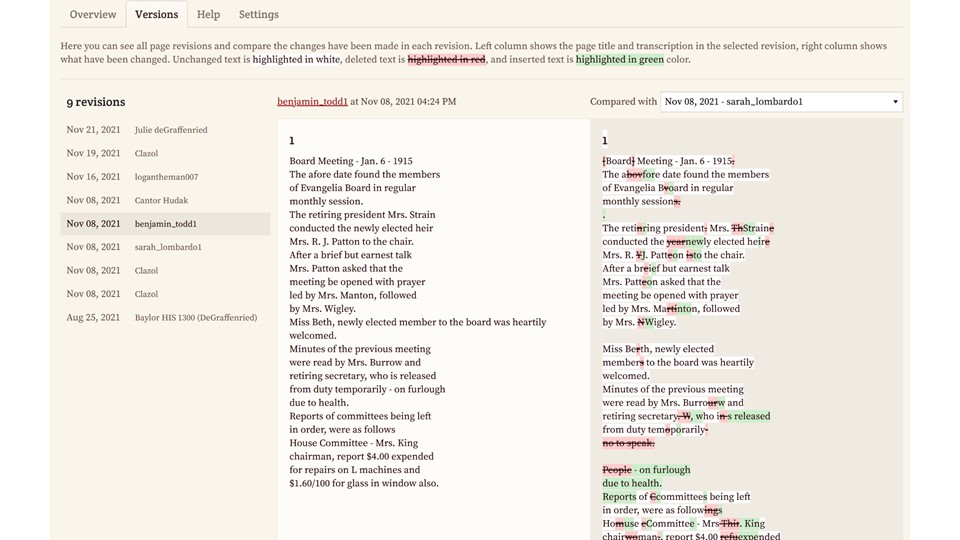

This is the versions tab on a page within FromThePage for Dr. DeGraffenreid’s project; you can see on the left everyone in the classroom who worked on it; you can compare a student’s version to any of the versions that came before it. I also love how this shows the collaborative nature of the work in this classroom.

Student reviews of the project were good.

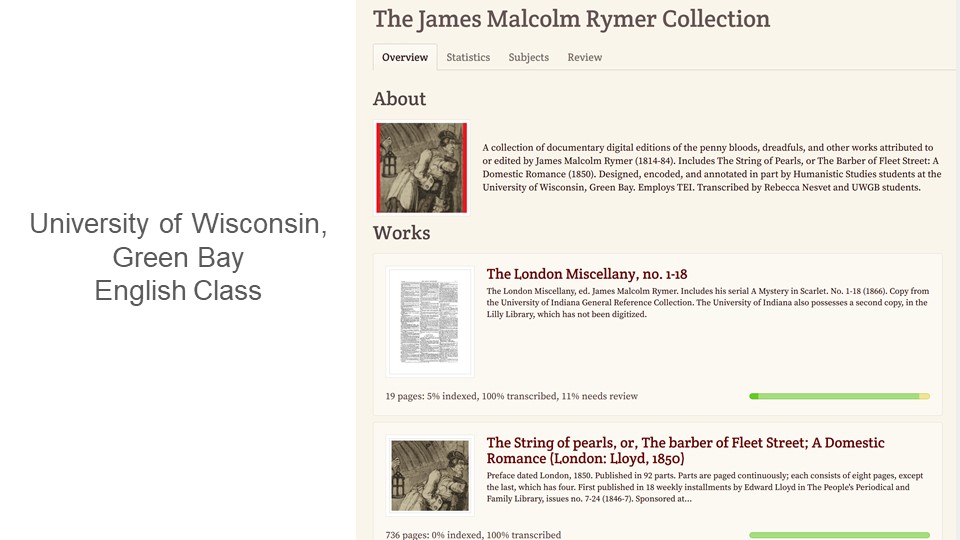

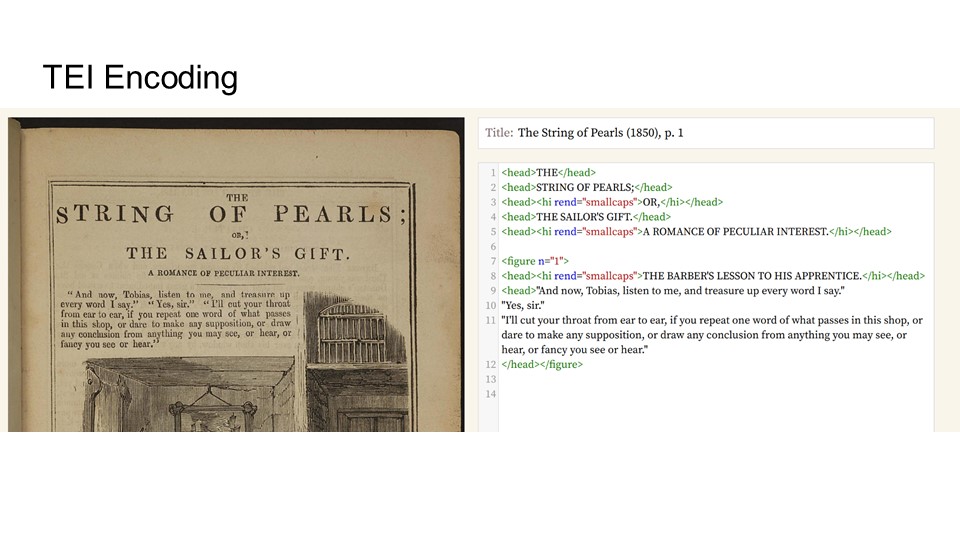

Rebecca Nesvet at University of Wisconsin-Green Bay teaches digital editions with Sweeney Todd. Firstly, students learn the original cultural context of this particular work, The String of Pearls, and the larger Sweeney Todd tradition.

In addition to correcting the OCR of The String of Pearls, students encode the text with TEI-XML. This teaches about digital editions and promotes critical reflection on digital media and culture.

One of the things Dr. Nesvet pointed out was that since all you needed was a web browser, it leveled the IT playing field; students do not need special software or equipment to participate.

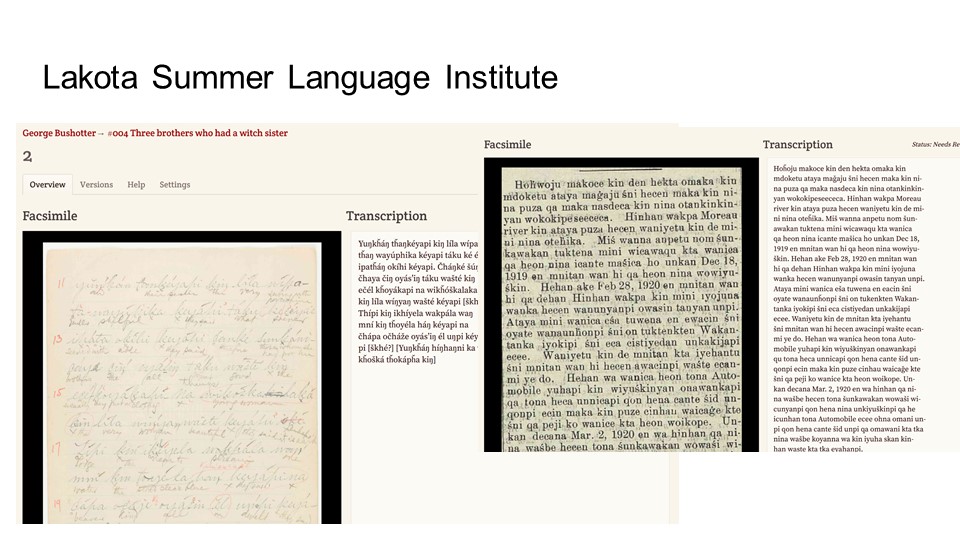

This is from a Lakota summer language institute for members of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe. It’s interesting that they worked with both handwritten records and newspaper accounts in Lakota.

Dr. Laura Morreale teaches Medieval history at a number of different universities. She has students transcribe and translate text in FromThePage.

These types of transcription projects really encourage deep reading. This quote from Dr. Laura Morreale: They come to speak about the author or scribe as an individual, as they come to know the hand, how the scribe abbreviated something or the preferred letter forms; it makes the text more personal, and students appreciate it as the work of another human, not just an abstraction of ideas on a printed page.

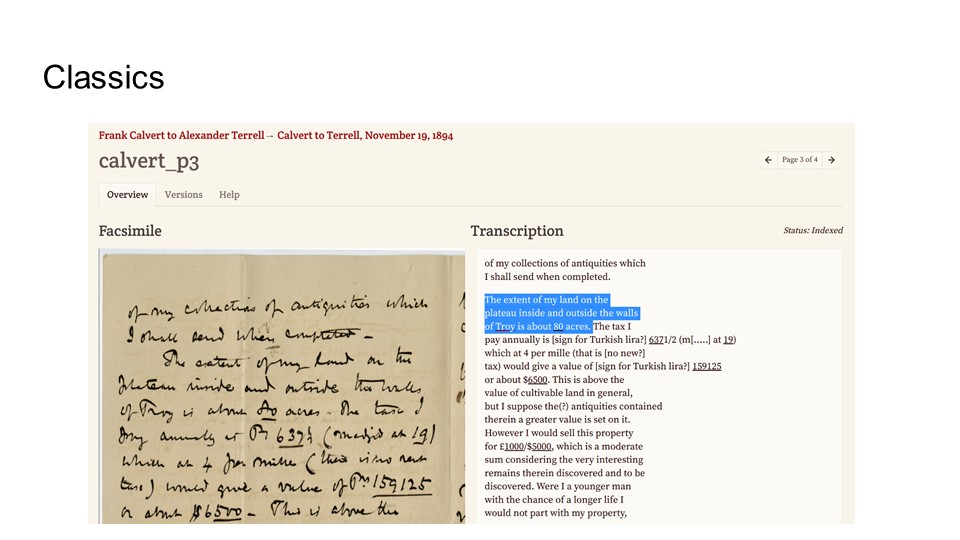

This is one of my favorites -- this is a letter offering to sell UT Austin the archeological site at Troy. Adam Rabinowitz uses it in an undergraduate honors class called "Tales of the Trojan War: from Bronze Age to Silver Screen".

Dr. Rabinowitz has a fun process:

1. First, Students were sent into the archives of the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at UT to find the collection of letters and take a selfie with one of them, proving they can navigate a finding aid and work with the archives staff to see primary source material.

2. Then Dr. Rabinowitz "unlocks" the collection of letters for the class to transcribe by adding the students to a private collection in FromThePage.

3. He then reviews and edits their work.

4. Finally, he gives them access to a larger collection of already transcribed letters in this collection and asks them to write a paper.

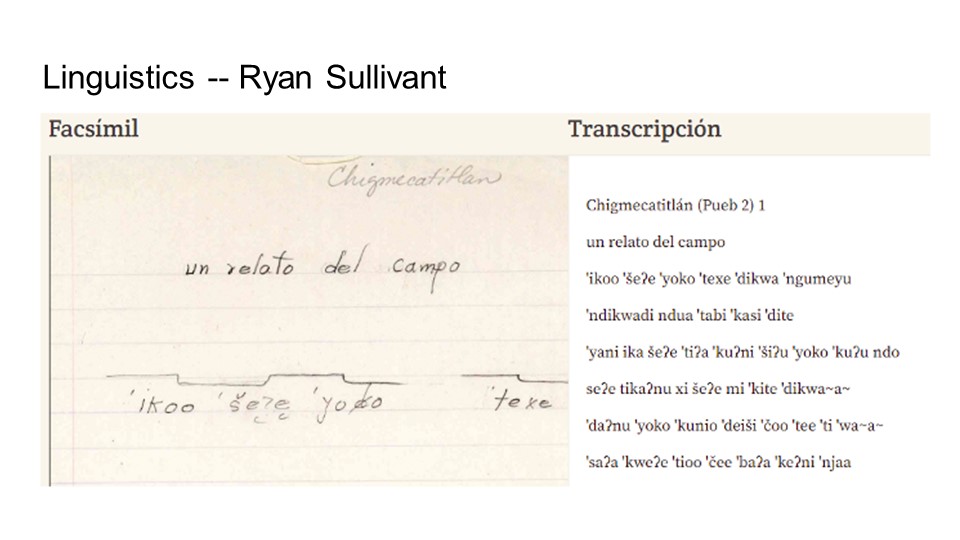

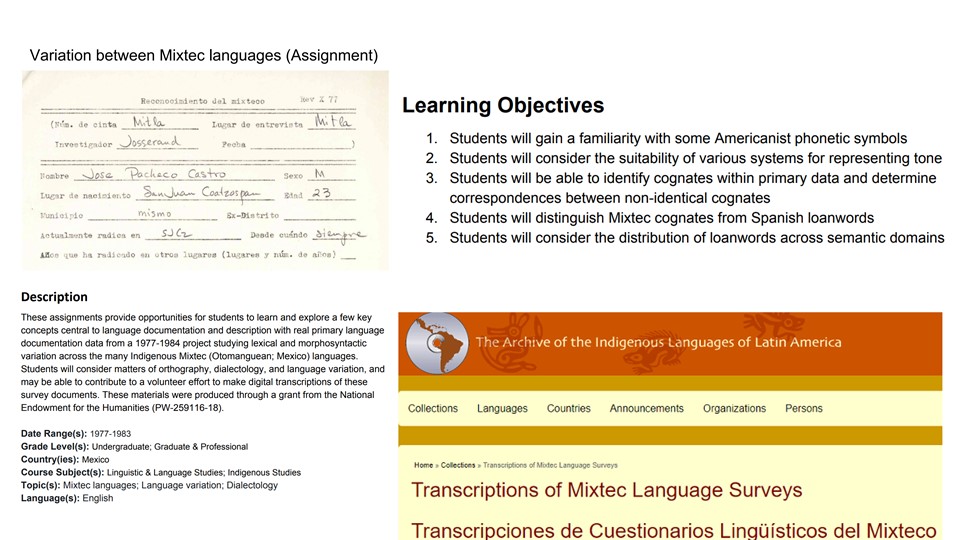

Ryan Sullivant at the University of Texas has had his linguistics students transcribing field surveys of Mixtec, an indigenous language of Mexico. The thing that’s most interesting to me is that he’s not teaching his students Mixtec!

Rather, he’s acquainting his students with the practices of linguistic field research. By working with historic language surveys, they can grapple with the kinds of notations, symbols and forms used by researchers in the field.

The resulting transcripts are added to the Archive of the Indigenous Languages of the Americas.

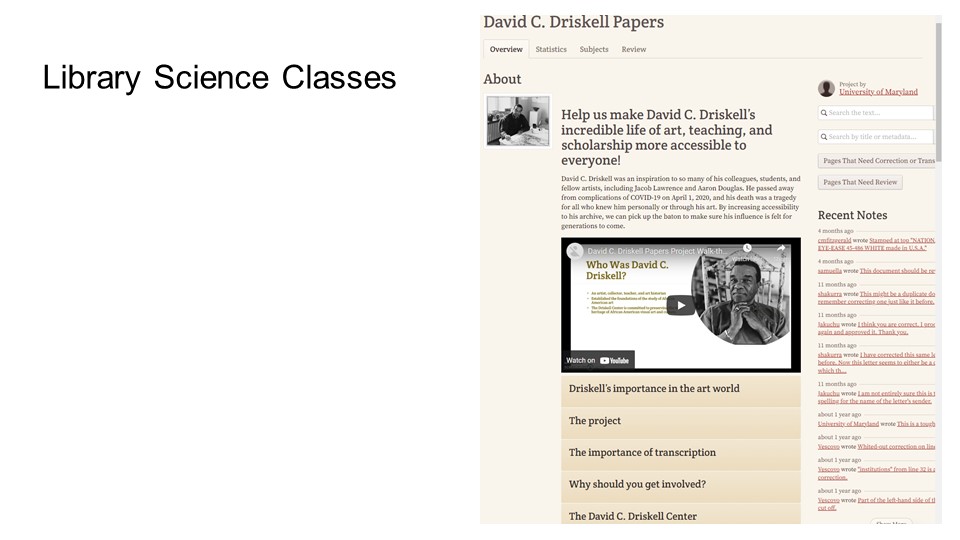

This is a bit meta, but Dr. Victoria Van Hyning has students create and run a live crowdsourcing project on FromThePage for the “Outreach, Inclusion, and Crowdsourcing” class she teachers University of Maryland’s College of Information Studies’

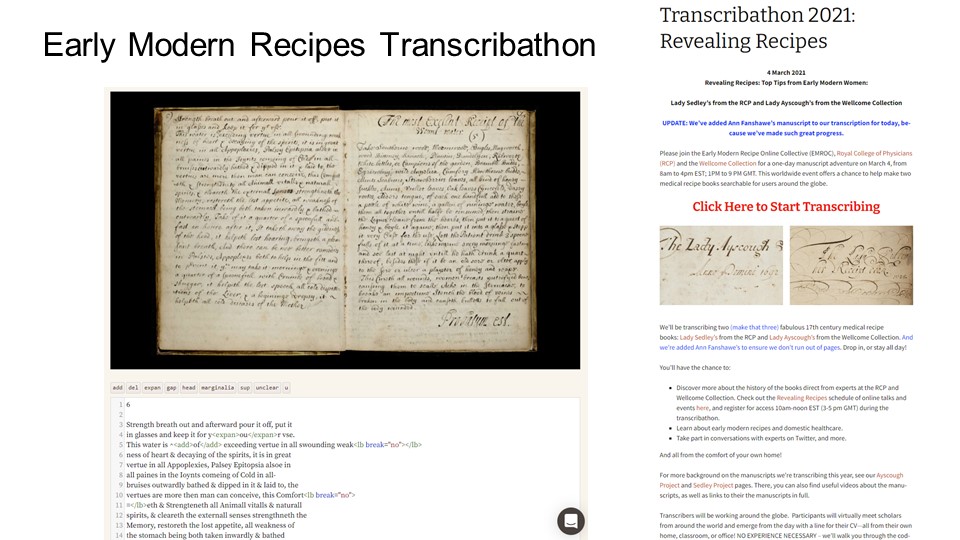

This one is a hybrid academic/public/classroom project hosted by the Folger Shakespeare Library called the Early Modern Recipes Online Collaborative. This collective of academics both invite the public and bring their students to the virtual event for a day.

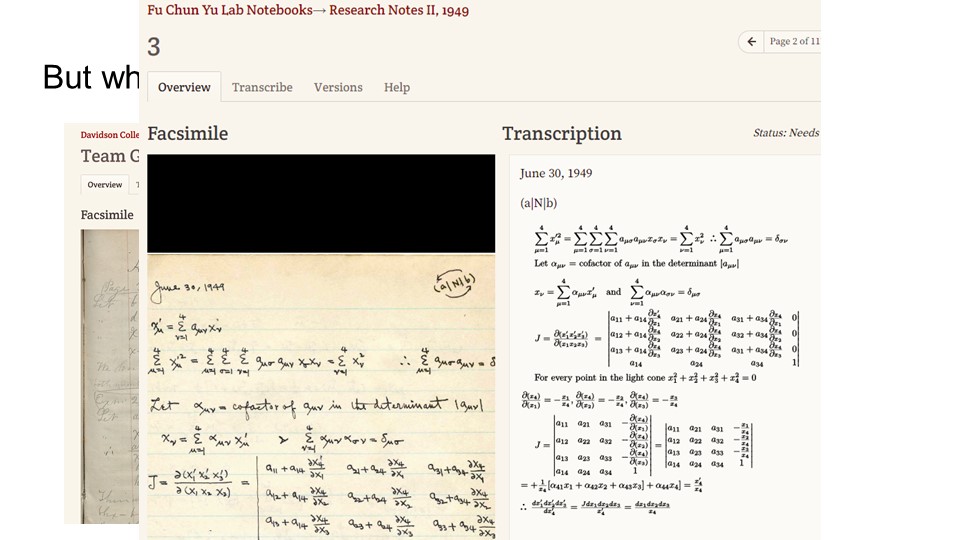

I also think there’s potential using transcription in STEM classrooms, although we haven’t seen that yet.. Geometry Notebook at Davidson College, Historical Chemistry Research Notes from Stanford. There are also a lot of historical field books and scientific observations -- that are useful to look at environmental and species change over time that would be interesting projects for the classroom.

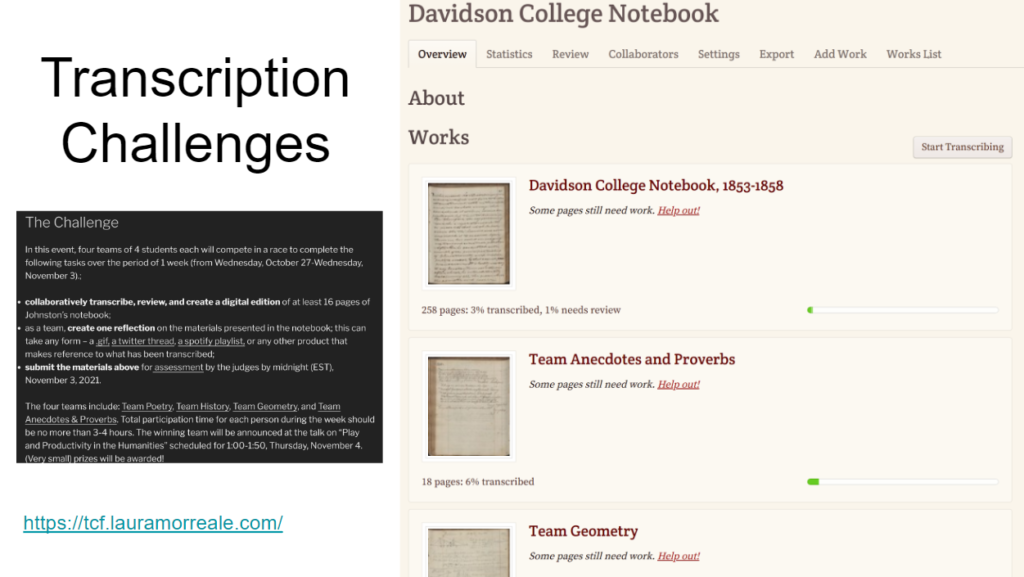

So Laura Morreale has set up a bunch of transcription challenges that medievalists across the world participate in. She tried the same approach for a transcription challenge at Davidson, and didn’t get nearly the same interest. Maybe it would work for events or graduate students? Learn more at Dr. Morreale’s transcription challenge framework website.

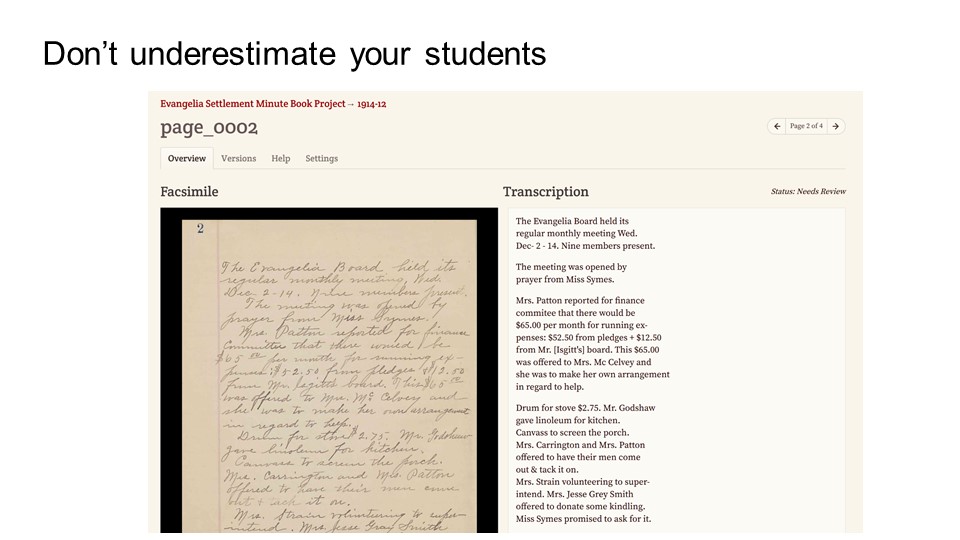

This is an example page from the Baylor project. Remember, this was a freshman history class -- arguably the youngest and least cursive-exposed students on campus. It’s from the 1910s, which is something to keep in mind -- the further back you go the harder the cursive is to read. This is pretty clear. These were also freshman history majors -- so they were perhaps more motivated than your average student in a distribution class.

But if you remember the version tab for a page in this project, we see that they collaborated A LOT. This was definitely something they worked together and emphasized the process as much as the results.

Working through discomfort -- that, to me, indicates you’re working at the edge of your abilities and actually learning!

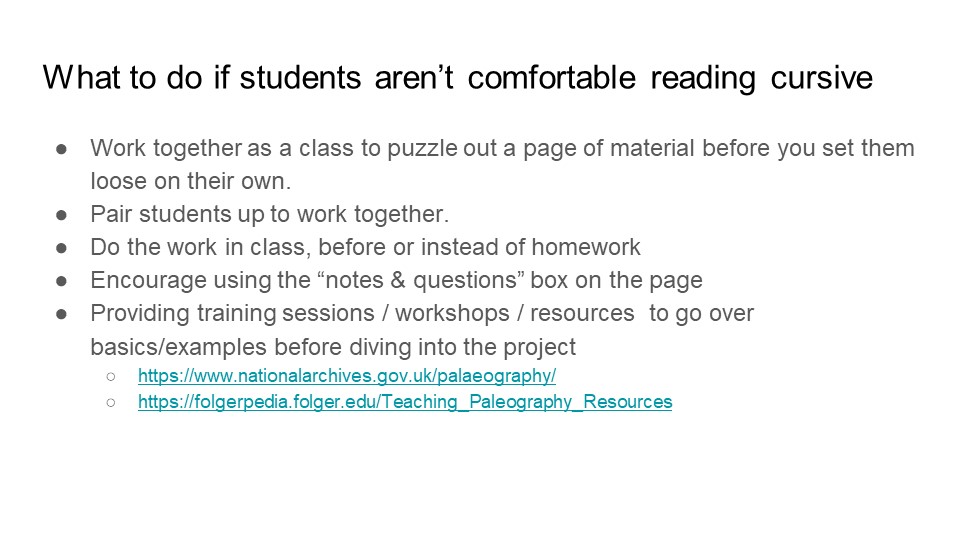

So a lot of our recommendations are to lean into that collaboration.

Baylor did the first; they put a page up on a screen on the front of the classroom and worked on it together.

Pairing works well with elderly handwriting readers + tech savvy youngsters, but just having someone to work with takes some of the pressure off.

If you work on this some -- or entirely -- in class, then students will have a stronger support -- from each other, even.

Encourage using the “notes” field to have students ask for help.

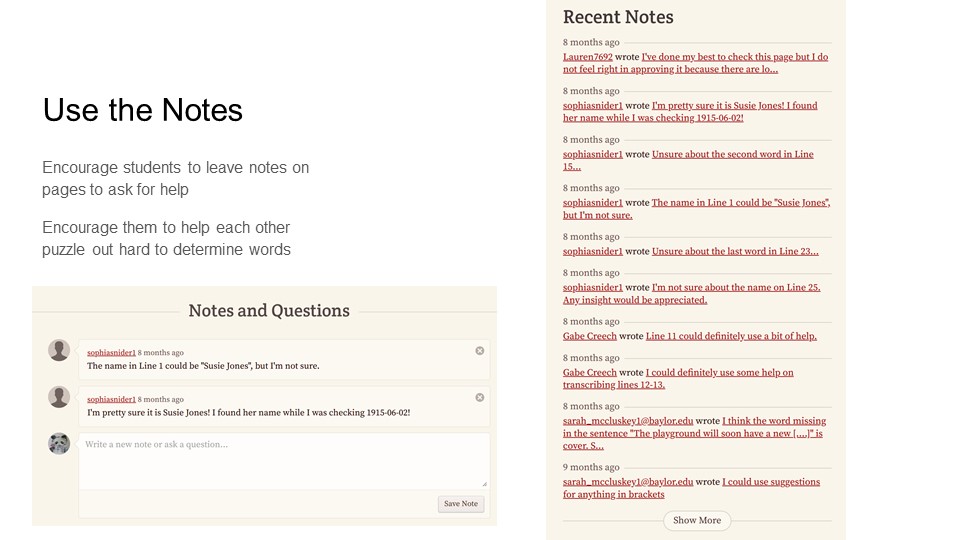

These are more examples from the Baylor project; on the left you see the “Notes and Questions” area that’s at the bottom of every transcription screen, and we see Sophia making a note about a hard to read name…. And then coming back later, when she has more information from a later document, to confirm her first read of the text.

For every project we show the notes on the right side of the project page, and you can encourage students to leave notes on the page and to help each other out.

This is a secondary school education packet from the Delaware Historical Society containing transcripts of WWII letters from Ralph Minker & his family. The transcriptions were done by family members on FromThePage, but are incorporated into a more accessible teaching packet.

This is a page from the Papers of Civil Rights Leader Julian Bond project at UVa. It’s much easier to read -- but it’s still important history! And it’s easier for students to work with.

So “just transcribing” is fine -- and it may take longer than you were anticipating. But if you’d like to build on that transcription work, there are more things you can do.

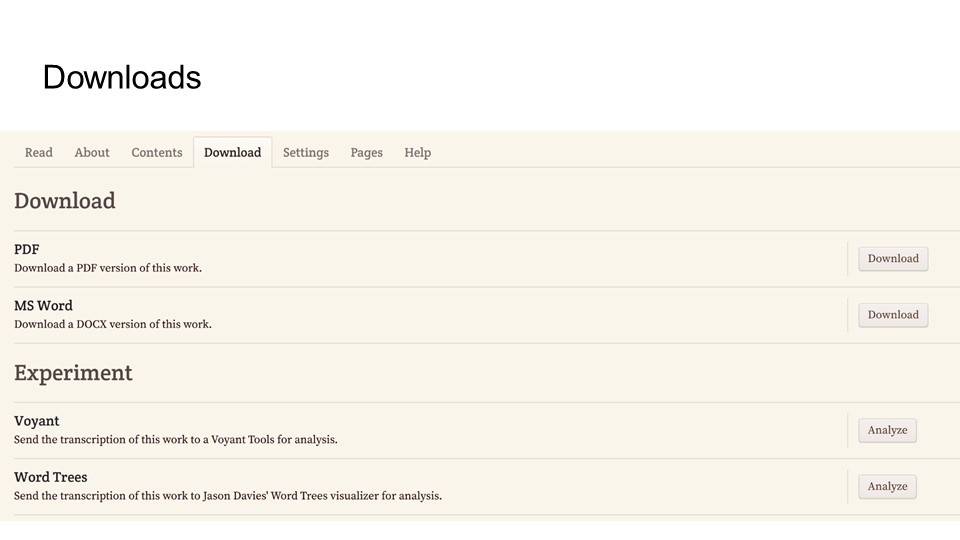

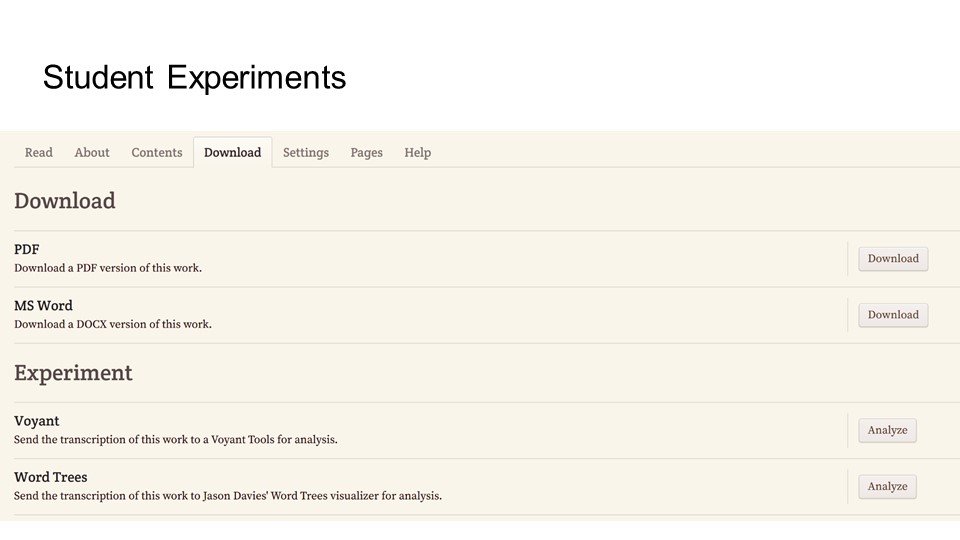

You can allow students to download individual document transcriptions as PDF or Word documents; perhaps as a starting point for something else.

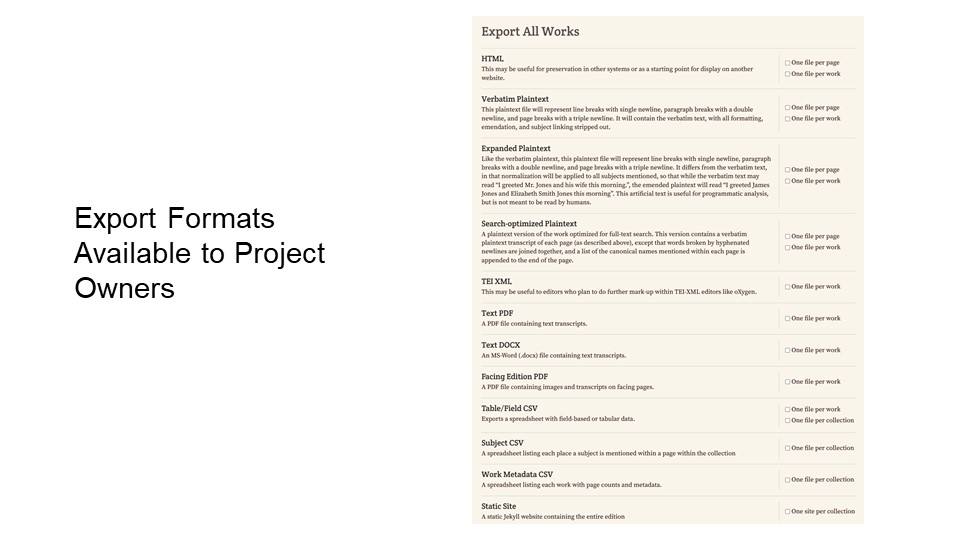

There’s a bunch more export formats available to project owners.

I know to my teenager “meaningful work” is really important. And for many students, the opportunity to contribute to something beyond their classroom is motivating.

We also supply easy ways to send documents to two text analysis tools for digital humanities classrooms.

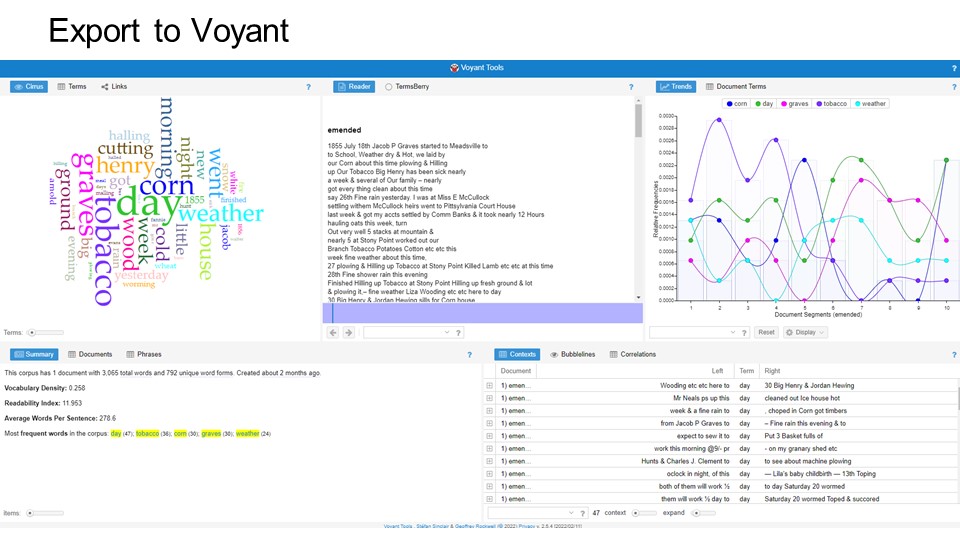

The first is Voyant, which can give you many different ways of text mining, from word clouds on up. It’s really user-friendly way to explore texts computationally, and it might provide some justification for the effort of transcription.

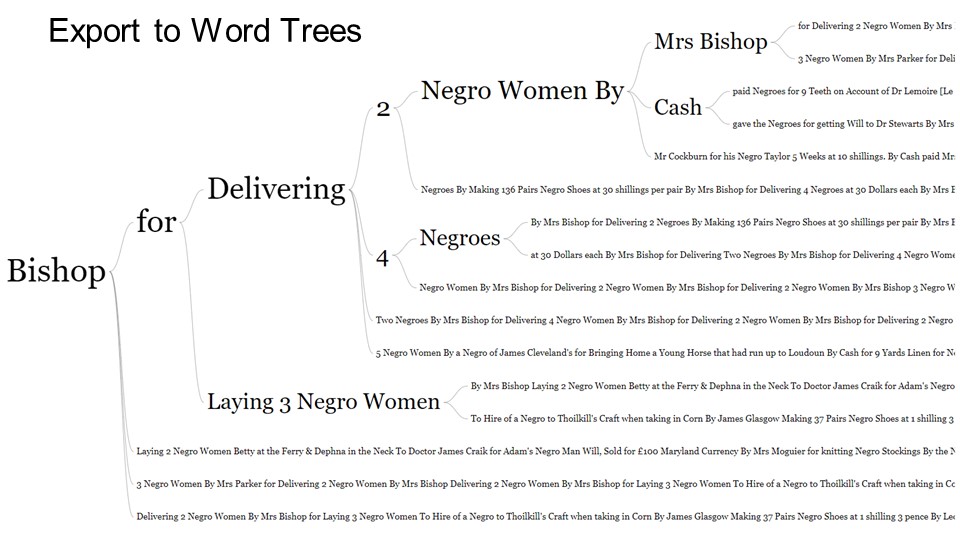

Another interesting way to explore content is to visualize the text in Jason Davie’s word trees. This lets you drill down on a specific word and see it in context of the sentences that follow or precede it. (In this case, we see example of midwife expenses in the George Washington Financial Papers.)

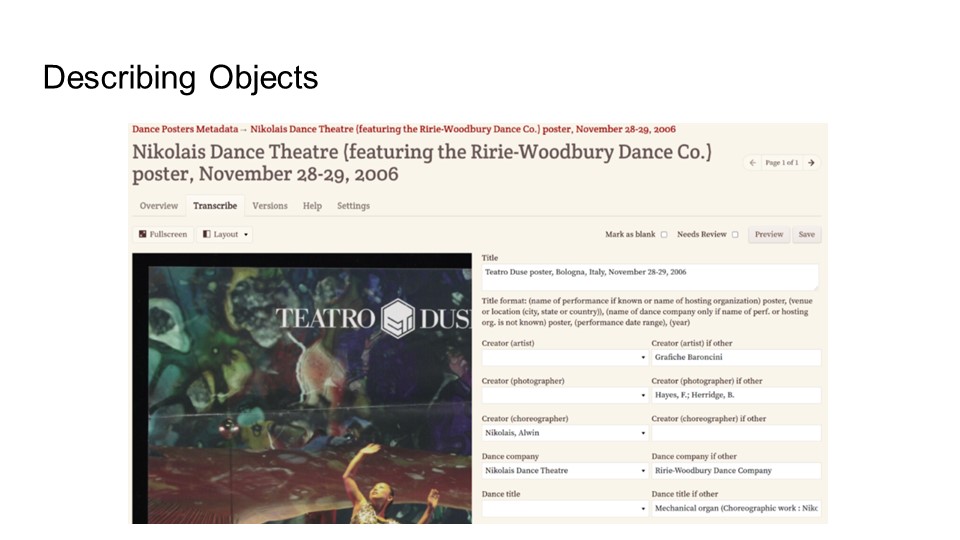

Ohio University used FromThePage’s metadata description form creation to create a form to describe dance posters in their collection.

You can do this type of metadata creation at the end of the transcription process as well; perhaps asking students for the sender, recipient, and data of a letter or having them summarize the contents of a document.

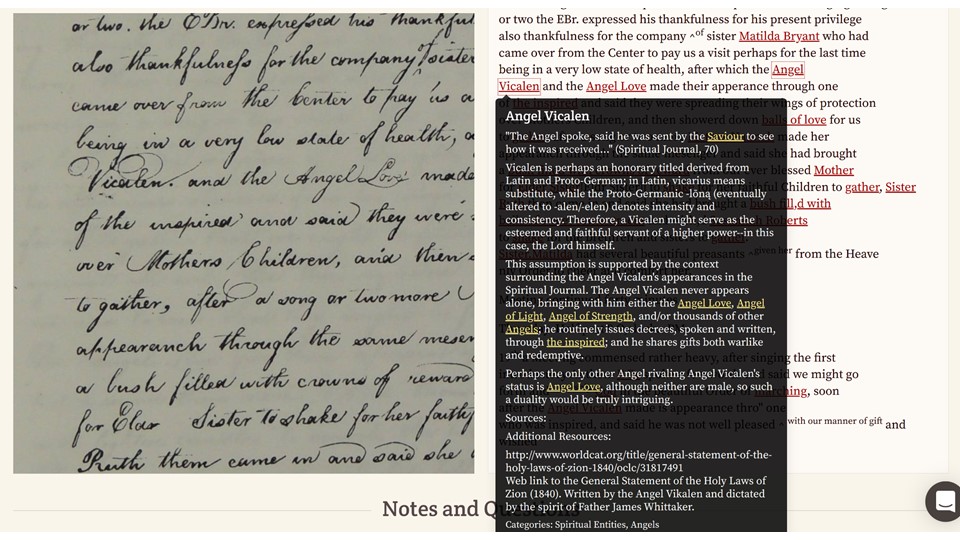

Joshua Guthman’s American History class transcribed, indexed and annotated a journal of spiritual visions kept by the Pleasant Hill Shaker community. You can see how students indexed and wrote articles about angels and other spiritual entities mentioned in the journal. This combines a deep reading of the text with secondary source research to explain what’s going on.

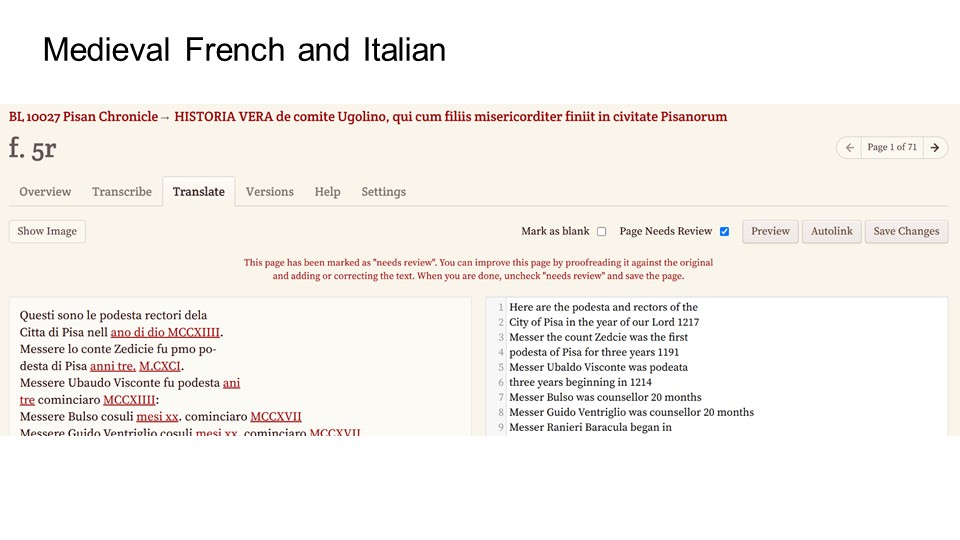

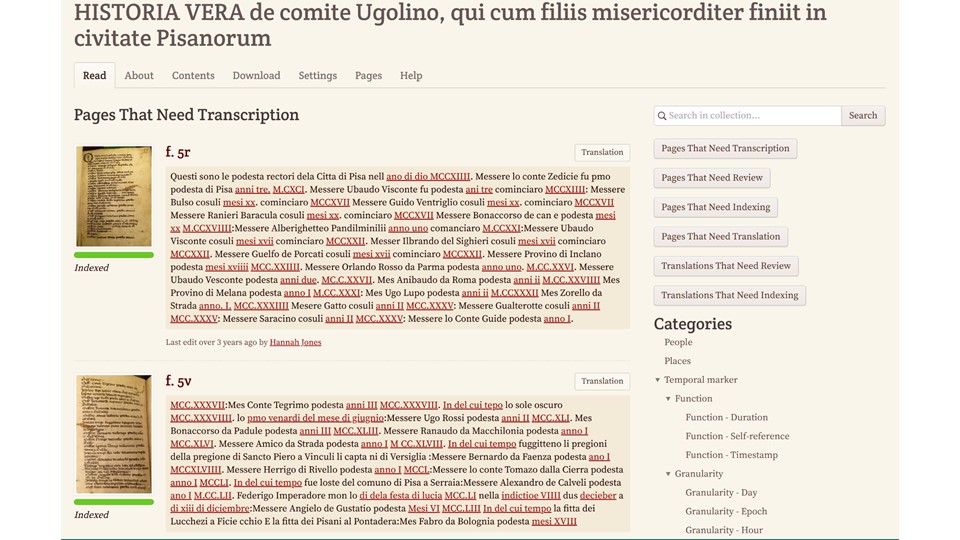

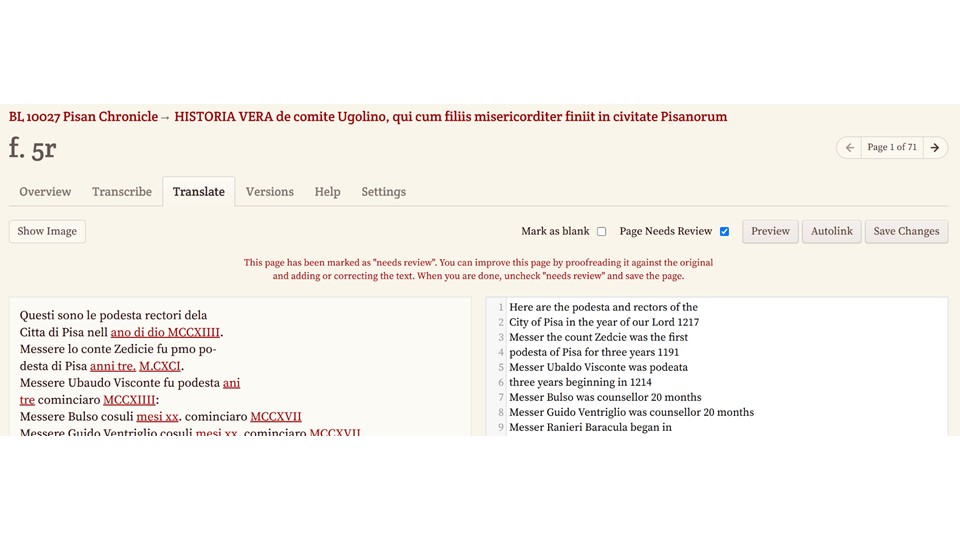

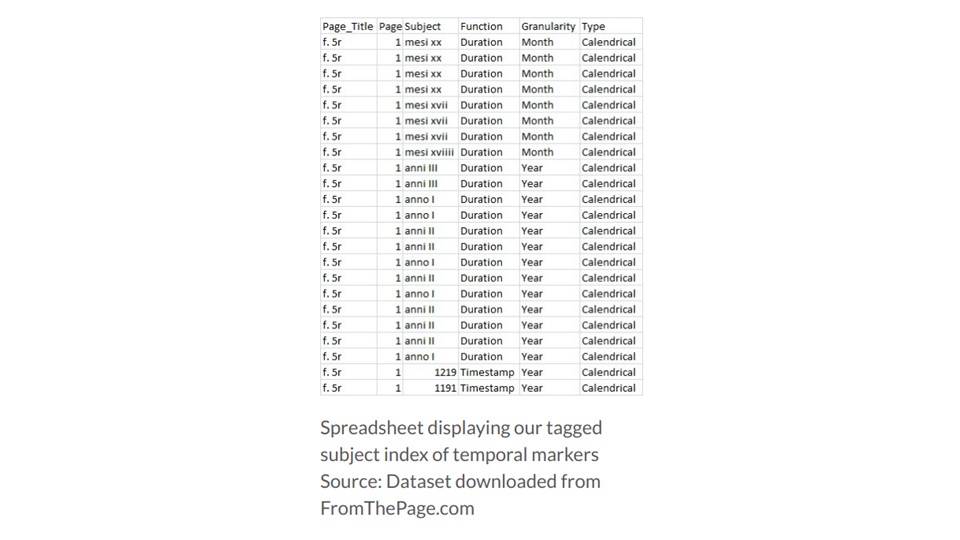

This was a graduate student seminar at the Catholic University of America, taught by Dr. Laura Morreale, where they looked at how time was represented in a medieval text from Pisa. They used an anonymous fourteenth-century chronicle from Pisa, Italy that focused on internal Pisan governance and factional conflict in Northern Italy.

Dr. Moreale is definitely a FromThePage power user.

This was particularly interesting because they pulled in the manuscript from the British Library and transcribed it and they pulled an early printed text from the Internet Archive and used FromThePage to correct the OCR.

Material doesn’t have to come from your institution! In fact, these two texts were super easy to import into FromThePage because they both were published using IIIF, so Dr. Morreale only had to copy and paste a URL to get them in.

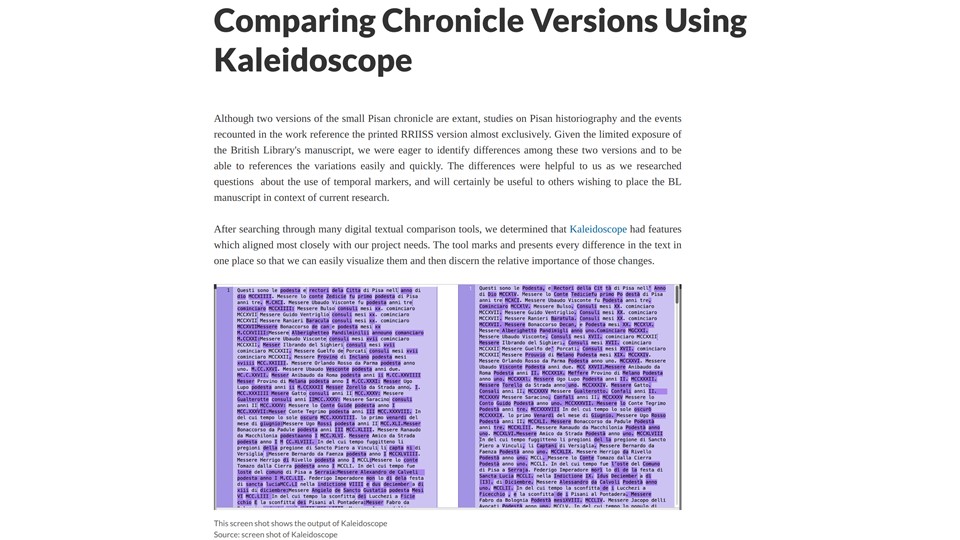

They exported plaintext files of both versions and compared their transcription of the manuscript with their corrected text of the printed version using a tool called Kaleidoscope.

They translated some of the text.

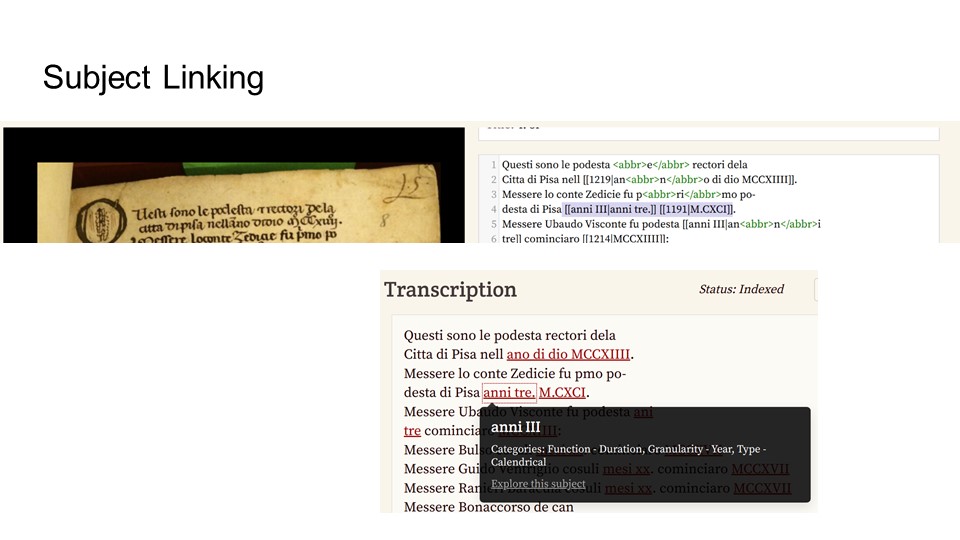

And they used our subject mark-up to mark up all references to time and days.

They categorized those temporal references by granularity, function, and type.

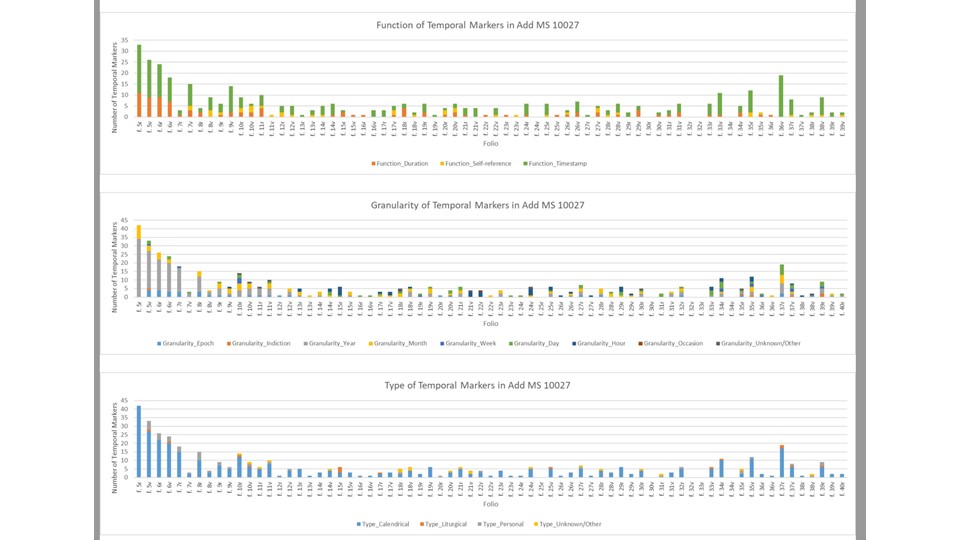

Then they exported a spreadsheet of those subject mentions and categories and…

Used them to examine the distribution of different types of temporal markers.

And they published all of this work in a scholarly publication: https://scalar.usc.edu/works/reckoning-time-in-medieval-pisa/index

So a very quick recap, because we’ve shown you a lot today.

We offer a 200-page trial.

This is probably enough for most classroom activities: https://fromthepage.com/users/new_trial

Let us know if you decide to use the trial in the classroom -- we are curious how it goes!

We’re going to end with this quote from Dr. Morreale: "Don’t worry too much about whether your students are "ready" to take on a transcription -- just throw them in there and tell them they will be fine, as long as they keep at it."